Lower returns on produce behind farmers’ distress

Profitability takes a hit as real MSPs have not risen over the years

Most commentary around rural anger in India has been focused on either the sector’s growth performance or government spending on agriculture. Such analysis is likely to present an incomplete picture at best. Government spending on agriculture is a small fraction of the total agricultural economic output. In 2017-18, the ministry of agriculture’s spending was less than 2% of agriculture’s contribution to Gross Value Added that year. And the narrative around rural distress has actually become more pronounced in the period which saw a revival in agricultural growth.

It needs to be understood that what matters the most from the farmers’ point of view is the return they get on their produce.

Stories of farmers dumping their output, especially perishables such as tomatoes, in acts of desperate protests in India are becoming increasingly common.

Such actions are triggered by a drastic crash in farm-gate prices, which often go below even the cost of cultivation. Such price crashes are rarely, if at all, matched by a reduction in prices of processed food items, such as tomato ketchup.

This is not entirely unexpected. Food processing industries are better equipped in terms of both financial and logistical capabilities to withstand cyclical fluctuations in markets than farmers.

To be sure, this asymmetry in economic abilities is not something new.

However, an HT analysis shows that the farmers have ceded further ground in this bargain under the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government in comparison the situation under the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) regime.

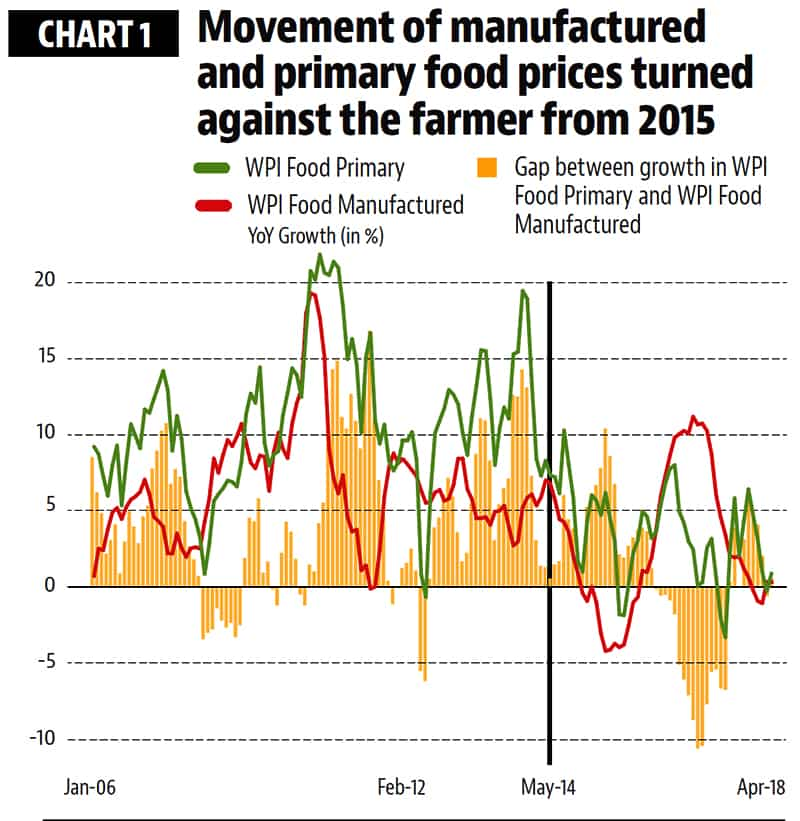

Looking at the trends in Wholesale Price Index (WPI) of primary food items and manufactured food items can help us capture this trend.

If the latter is increasing at a faster rate than the former for a prolonged period, one can argue that food processing industries are effectively squeezing farmers’ incomes by not passing on the benefit of higher prices they are receiving back to the farmer.

If, in contrast, primary food item prices are rising at a faster rate than that of manufactured food items, it would mean that the food processing industry is unable to pass on the higher prices it is paying for raw materials to consumers. WPI is used due to two reasons.

One, it allows the analysis to go back to the UPA period unlike the latest Consumer Price Index (CPI) series, which starts in 2012, towards the end of the UPA’s rule. And two, it is more representative of the prices received by farmers as they sell their output in wholesale markets.

A monthly analysis of annual change in each of these sub-components of WPI shows that for most of the time the UPA was in power, WPI for primary food articles was growing at a faster pace than WPI for manufactured food items. The trend almost reversed from the second year of the NDA government’s rule.

This becomes clearer from looking at the columns in Chart 1 which plot the difference in annual growth of WPI for primary food items and manufactured food products. Difference between growth in prices of primary food items and manufactured food items first started coming down and then went into negative territory for almost a year. After a recovery this value seems to be heading down once again. (Chart 1)

What might have caused this? Because the trend started much before the implementation of demonetisation and GST, there has to be something more to it.

The answer seems to be muted growth of Minimum Support Prices (MSP) under a large part of NDA period.

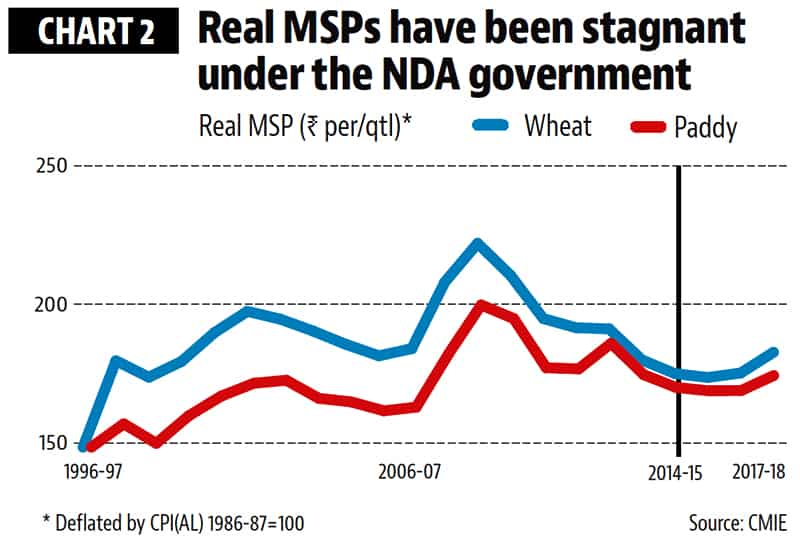

Governments rarely decrease nominal MSPs from their existing levels. However what matters is the real increase in MSP which allows us filter out the inflationary component in MSP hikes.

Consumer Price Index for Agricultural Labourers (CPI-AL) has been used to deflate MSPs. This is because while not all farmers receive MSPs, these do act as a strategic anchor of farm prices and hence rural incomes in the country. Real MSPs for both paddy and wheat were the highest during the first UPA government. UPA-II’s rule saw a large decline in these prices. Real MSPs have been largely stagnant during the present government’s tenure.

To be sure, international prices also play a role in setting up of MSPs as well as overall farm prices by the government. The sharp rise in MSPs under the UPA I was in keeping with the spike in international food prices. Food and Agriculture Organization’s food price index increased by 48% between 2004 and 2008. It declined by 19% between 2011 and 2015. However, it has actually increased by 11% between 2015 and 2017. (Chart 2).

The food industry seems to have taken a cue from the Centre’s policy of keeping real MSPs from increasing. The farmers, deprived of their strategic anchor of rising MSPs, have been left to fend for themselves. It remains to be seen whether the Centre is willing to do its bit in turning the terms of trade in favour of farmers as elections come closer.