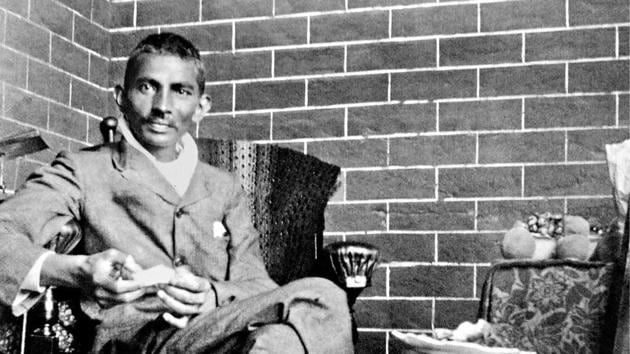

Learning to become a political activist

The debate on social media often ignores the changes Mahatma Gandhi went through in subsequent years when he sought to travel third class in trains

[In 2019, Hindustan Times marked Mahatma Gandhi’s 150th year with a special series comprising reportage, invited columns, essays and archival material. On the occasion of the Mahatma’s birth anniversary on October 2, this article has been published from a curated selection of our coverage.]

MK Gandhi’s 100th birth anniversary in 1969 was celebrated in South Africa at a time when the apartheid state ruled strong: significant black political organisations in the country were banned or forced into inactivity and individuals were placed under house arrest orders.The celebration was organised by the Phoenix Settlement Trust and included the opening of a Gandhi Museum and Library at the settlement, as well a Mahatma Gandhi Clinic. The last opened in the printing press building that once housed Indian Opinion, a newspaper that Gandhi had founded in 1903, and which had ceased publication in 1962. Leading figures gave speeches at Phoenix and in major urban centres, reminding people of Gandhi’s call to action at a time when the laws were equally unjust, and how satyagraha was conceived on South African soil.

In 2019, as we prepare for the 150th birth anniversary, Gandhi’s reputation in South Africa has taken a knocking. Just in August, the Economic Freedom Front (EFF), a party of populists, moved a motion in the Johannesburg City Council for the removal of Gandhi’s statue at a city square where a young Gandhi once had his law office. While the EFF lost this motion by 20 votes to 226, that the debate took place at all is significant.

Much of the conversation that takes place in social media about Gandhi centres around his attitude towards black South Africans, his use of pejorative terms and his claim for better treatment for what he regarded as the more civilised Indians.

Also Read: On authentic leadership of Mahatma Gandhi | Opinion

Gandhi, who was 24 years old when he began to make his mark in politics in Natal, should have known better for he detested the term “coolie” when it was applied to him. In defending Indians’ right to the franchise in Natal, he fell into the trap of engaging the authorities on the question of what constitutes a civilised person. While challenging the racial hierarchy that the settlers were constructing, he did so only in so far as they sought to lower the status of Indians.

The debate on social media is unforgiving and often ignores the changes Gandhi went through in subsequent years when he sought to travel third class in trains to get a taste of what Africans experienced. It ignores that Indian Opinion regularly published news about African grievances about restricted land rights and daily petty discrimination and commended African achievements such as the educational work of John Dube at nearby Ohlange Institute and his election as president of the South African Native National Congress. Gandhi’s final campaign in 1913, which drew Indian women to become passive resisters for the first time, was in fact inspired by the struggle of African women against the Pass laws (which stipulated that Africans in urban areas had to carry a Pass on their person or face prosecution). In his book, Satyagraha in South Africa, Gandhi admonished Indians in India about their predilection for light skin and wrote admiringly about the African body.

Who could claim at 45 to be the same person they were at 24? The South African Gandhi was not perfect — he began young and was politically inexperienced, but his life was marked by change. While not discounting the importance of recognising the flawed Gandhi, even if erroneously judged now in contemporary contexts, it is worth reflecting on how extraordinary his South African years were. In these years, he was not just a lawyer or secretary of a political organisation but he made going to prison a matter of praise and courage and he tackled that important human tendency for fear — from authorities or of loss of possession. In these years, he became a prisoner, a journalist, a farmer, a teacher, a food reformer, a healer of the body and he gave up a legal career which had brought him wealth. We should not forget he was also a husband and father of four sons, and far from neglecting his sons, he sought to mould them according to his ideals.

In his days as a novice petitioner in Natal, Gandhi brought abundant energy to tackle white dominance. No prior Indian political activity in the colony would have pulled off the monster petition (against the disenfranchisement of Indians) of 8,889 signatures in 1894. As a petition writer, Gandhi drew on literature, read official reports, commissions and statements made by members of the legislature in order to challenge restrictions on trade licences, closing off immigration, and even the removal of political rights. Never had there been so much campaigning in India as there was in 1896 to alert the Indian public about daily life in racist Natal.

Though Gandhi lost many of these battles, he continued to believe in the idea of an imperial brotherhood and that there was a such a thing called British justice. In his last decade in South Africa between 1903 to 1914, Gandhi began a campaign of satyagraha that saw brilliant acts of defiance such as the burning of passes in a bonfire, cross border immigration violations and a march comprising thousands of striking coal mine workers. In the mind of the Indian workers, Gandhi had become a raja to save them. Gandhi used Indian Opinion to mobilise readers, to educate them about an ethical and moral lifestyle and to highlight the harsh conditions of indentured workers on the estates and mines. His thoughts on what constituted good journalism, one free from advertisers, began to crystallise in this period. He also used the paper to establish his own leadership of the movement. It is this Gandhi and the man who went on to lead India’s liberation struggle, who would inspire generations of South African resisters.

Also Read: A newspaper with a view

Gandhi also challenged social norms in his own house by bringing together white and Indian, Muslim, Hindu and Christian, and those of different castes and languages under one roof. His concept of family began to change when he established two settlements, Phoenix and Tolstoy Farm, where inhabitants worked jointly on causes. He insisted on a lifestyle based on manual labour, nature cure, vegan food habits, and self discipline. Unlike in his ashrams in India, individual freedoms in such matters of food and celibacy were permitted. The idea behind the settlements was to train future satyagrahis and educate young children to develop pride in Indian heritage. Religious practices now identified as Gandhian — respect for all religions — evolved at these settlements. Women were encouraged to work in the press.

Today, Phoenix is one of the most important heritage sites in South Africa, for it served as an example of how human beings could live differently.