‘In line with public trust standards’: How SC judges arrived at Central Vista decision

Majority verdict held it is not the court’s concern to enquire into priorities of an elected government.

Arriving at a decision granting approval to the Central Vista redevelopment plan was not straight forward. The majority decision of the Supreme Court, authored by two on a three-judge bench, laboured to arrive at a conclusion by examining underlying constitutional principles, environmental safeguards, and the standard of judicial review to be maintained in examining an iconic project of this nature.

Some of the important aspects that make the 611-page judgment interesting are:

Rule of law and democratic due process

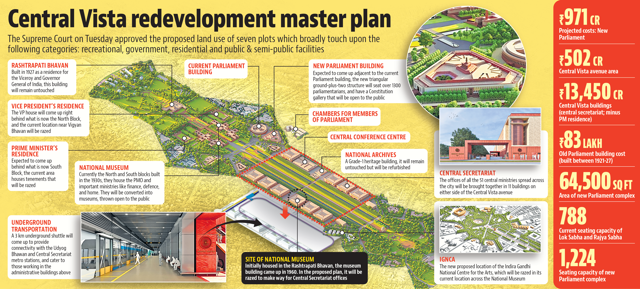

The petitioners implored the apex court to apply the “rule of law” instead of “rule by law”, which they argued, the government followed to bypass the “democratic due process” in order to obtain various approvals and clearances for the project worth over Rs 15,000 crore (this does not include the PM’s residence, and some other elements of the project).

The majority verdict by justices AM Khanwilkar and Dinesh Maheshwari maintained that the rule of law provides a constant trigger to any state-citizen exchange and calls upon the court to strike a balance between two entities both bound by the same principle of superiority of law. But it added that the import of an expression like “democratic due process” in an administrative matter is fraught with serious consequences, for it will mean a decision on the subjective notion of the court, and not in accordance with the “procedure established by law”. An expansive approach towards democratic due process, where issues of constitutional rights are not involved, will be tantamount to substituting the government’s decision with the wisdom of the court regarding a better course of action or a policy.

“Even if a Court finds it debatable, that can be no ground for the Court to quash an action taken strictly in accord with the prescribed procedure,” said the majority view, adding application of democratic due process will lead to withdrawing the task of governance from the democratically elected representatives and the executive by creating an illusory bar on the exercise of their power to function freely despite being within the four corners of the law.

Plea for a heightened judicial review

Keeping a safe distance from executive policymaking functions, the judges held that it is not the court’s concern to enquire into the priorities of an elected government. “We cannot be called upon to govern. For we have no wherewithal or prowess and expertise in that regard. Judicial review is never meant to venture into the mind of the Government and thereby examine validity of a decision.”

The judges noted with concern the misuse of PIL (public interest litigation) jurisdiction by a section of people in society who seek substitution of the government’s view with their view by filing a PIL. “Judicial time is not meant for undertaking a roving enquiry or to adjudicate upon unsubstantiated flaws or shortcoming in policy matters of Government of the day and politicize the same to appease the dissenting group of citizens — be it in the guise of civil society or a political outfit.”

Referring to the present set of petitions challenging the project, justice Khanwilkar said, “We need to say so because we had to spend considerable time and energy on this matter despite the pandemic situation, which at the end, we find to be devoid of substance.”

The petitioners argued that the courts must adopt a “heightened” judicial review. Discarding this argument, the bench said, “There is absolutely no legal basis to ‘heighten’ the judicial review by applying yardstick beyond the statutory scheme and particularly when the Government has accorded no special status to the project and has gone through the ordinary route of such development projects as per law.”

Public participation

The majority verdict addressed the petitioners’ complaints as regards the absence of sufficient public participation in the entire process. The court discussed the principles of natural justice while underlining that the subject matter of a development project, with no direct bearing on lives and livelihoods, cannot be equated with a project which has a direct impact.

It noted that whether in a given case, personal oral hearing is to be provisioned for, or mere representations be invited, or public discussion is called for, is a matter for the legislature to make a law in that regard and that a court can’t prescribe a legislation in this regard.

“The citizens are completely free to advocate any notion along the government policy or the manner of making it in their free exercise of right to speech and expression, but enforcement of such notion cannot be fructified by resorting to judicial review...No country with a sizeable population like ours can give a promise of direct participation to every individual in the decision-making process (of the government) in administrative matters unless the law so prescribes,” it held. Thus, the scope of public involvement in government processes, it said, is a matter dependent on legal framework of a country and the court should be loath to venture into that area.

Environmental concerns

While accepting the environmental clearance granted for the development of the new building, the majority decision felt it proper to direct the Central Public Works Department to set up smog towers of adequate capacity at the project site and install smog guns throughout the construction phase to mitigate pollution.

“Time has come to advance the intent behind improving air quality a mandatory feature for modern buildings and more particularly during the phase of construction of such major projects in the cities most affected by air pollution.” The court called upon the Ministry of Environment and Forests to issue directions.

In addition, the court asked the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs to issue general directions to ensure smog guns and smog towers are made mandatory while constructing government buildings, townships or other major private projects.

This shall be made an integral part in all future major development projects for grant of development permissions, particularly in cities with bad track record of air quality, the judges held.