HT @ 100: Army to politics — Snippets from a storied journey

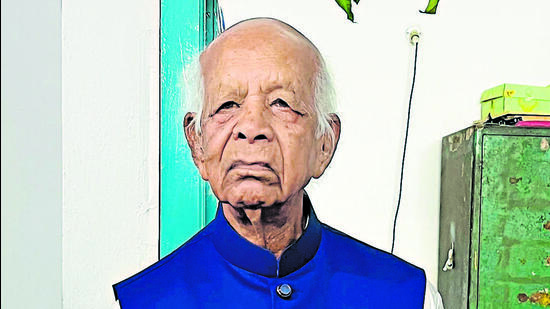

Murthy, born on June 15 ,1924, spent his life in Hyderabad, growing up in a confluence of tongues and traditions

M Krishna Murthy often remembers Nizam Mir Osman Ali Khan.

When Murthy was a toddler, the Nizam still ruled Hyderabad and India was 13 years away from Independence. India’s largest trade fair, the “Numaish Masnuāt-e-Mulki”, or an exhibition of all things local, was held at the city’s famed public gardens built by the Nizam, who was, by some accounts, among the world’s richest men. Hyderabad’s roads were washed and watered every morning and the streets leading to the Nizam’s many palaces were lit up.

“The Nizam was an enigma,” said Murthy. “Some say he was generous, others say he was miserly. But it was just a matter of pride to be his subject.”

Having spent much of his life between Chadrkhandil and Bazaarghat, neighbourhoods in the old city, Murthy’s most distinct memory is of the Nizam’s two-time Prime Minister, Maharaja Sir Kishen Pershad.

“Kishen Pershad ji used to stand in his silver Rolls-Royce Phantom and throw newly minted coins as we lined the streets. We used to call out to him as ‘Shad’ (happy, his pen name) or utter Allah’s name and he would throw fistfuls of coins at us. I still have the two paise and three paise,” Murthy said.

And even after 100-odd years have passed since he stood on those manicured streets, Murthy doesn’t look back at that display of opulence with disdain. “Hyderabad never lacked in anything. There was always plenty and the Nizam’s ministers used to give us all inaam every Diwali and Eid,” he said.

Tryst with the army

Till a few years ago, Murthy travelled across the city on public transport to meet his friends and relatives. Now, age has prevailed. But, crucially, the city has lost “that magnetism”, said the 101-year-old.

The city’s old landmarks, the tombs and ‘baradaris’ of Sufi saints and ‘kamans’, or gated archways that led up to the palaces are gone from the skyline. The sunshine now bounces off tall towers of glass and metal. “Hyderabad then was about vineyards, gardens, mosques, and palaces,” he said.

Murthy, born on June 15 ,1924, spent his life in Hyderabad, growing up in a confluence of tongues and traditions. A polyglot, Murthy is fluent in Telugu, Urdu, Hindi, English “and some pedestrian Marathi”, which he picked up during his time in Pune, where he joined the Indian Army.

He served between 1941 and 1951, watching keenly from within the system as the country transitioned from British subservience to freedom. But he also watched keenly from afar as his home, once part of a princely state, blended into independent India in 1948.

Murthy was part of the Remount Veterinary Corps (RVC), an administrative and operational branch of the Indian Army, one of its oldest formations.

From Pune, work took him to Ambala, and then to Meerut. where he looked up at the skies with promise as the Tricolour was hoisted on August 15, 1947.

“Being in the Army, we weren’t part of the politics or the nationwide protests. But I remember the day we got our Independence. As a 20-something-year-old, I did not realise the value of it, but looking back, I know I have lived to see something truly historic,” Murthy said.

Murthy lives with his two daughters and son in Yousufguda in central Hyderabad. He lost his wife, Savitri Devi, in 2019, when she was nearing 90.

A compliment from the Field Marshall

He bats away the encumbrances of age with ease as he sits on the floor on his mattress and entertains visitors. The sharp eyesight and keen intellect have remained loyal to him, even if his hearing hasn’t.

Murthy exercises for nearly an hour in the morning and credits the army’s discipline for his sanguine state and harmony.

“I used to be very good at football. It was one of the reasons I was picked to be part of the army,” he said. But the other reason he chose to be part of the army was his difficult relationship with his first employer, an electrical store owner.

His day job included running errands for the owner, a “foul-mouthed man who made people work many hours extra, but didn’t even pay us properly”.

Murthy then, buoyed by his sporting prowess, served in the armed forces for a decade. His fondest memory was receiving a compliment from Field Marshal KM Cariappa for his handwriting.

“It was around 1946. We were in the Meerut Cantonment. We had a roster for all duties and on that day, it was my turn to list every officer’s duties on the blackboard. General Cariappa passed by the board and asked the junior cadet to summon the person who had made the list. When I bolted from my run on the ground and saluted the General, he appreciated my handwriting and allotted me the duty to write on the blackboard until I was transferred out of Meerut.”

Murthy keeps an eye on national politics and followed this year’s general elections held earlier with child-like enthusiasm.

But, he said, politics has changed. Having lived through his entire prime ministership, Murthy has a soft corner for Jawaharlal Nehru, the country’s first premier.

“I’ve only ever liked two prime ministers — Kishen Pershad and Pandit Nehru. They knew what was good for the country.”

Chance encounter

Around 1950, Murthy recalled meeting BR Ambedkar who was in the city to resolve a political impasse between Congress leaders. Murthy was among the officers who were part of Ambedkar’s security detail.

“Three of us accompanied Ambedkar everywhere he went in Hyderabad. I always wanted to sit inside the venue and listen to him address Congressmen, but we were asked to stay outside and stand guard,” he said.

Murthy returned to Hyderabad in 1952 as the army worked to thin out the swelling Veterinary Corps.

There, he began the next chapter of his life — as a male nurse and compounder at Pradeep Clinic in Gunfoundry. “It was a quiet, routine life — work at the clinic and nursing home, and heading back home by 6pm.”

By then, Hyderabad was already changing. “Hyderabad changed a great deal after I returned from the Army. I was not happy with the administration.”

He asked Marri Chenna Reddy, a Congress leader, for a ticket from Bazaarghat, and was promptly declined.

“I went to the Election Commission and asked for a symbol for an independent candidate. They allotted me a cycle” he said. Decades later, one Mulayam Singh Yadav would pick the same symbol for his fledgling outfit — the Samajwadi Party.

What began for Murthy was an ambitious project — to unseat the sitting Congress legislator as an Independent. Around him were a ragtag group of school and college students, who drove the shoe-and-leather movement to elevate him to the state assembly.

The students pooled in ₹100 - the fee the Election Commission charged at the time. “They regarded me as a soldier who fought for the country,” he said.

“I walked on foot to campaign and the boys used to beat the drums and ask people to vote for me. I had no pamphlets or other election material.”

The drumbeats ended abruptly. “I got very few votes and lost my deposit,” he said.

His political sojourn ended with that bruising attempt and he returned to the quiet, perfunctory cycle in the clinic.

And he didn’t get off that cycle, till he retired in 1985.