How to get a religion: Veerashaivas and Lingayats stake their claim in Karnataka

What’s the link between the deaths of three dissenters and followers of a faith who now demand a ‘separate religion’ in poll-ready Karnataka

Real weapons are hardly ever a match for the weapon of criticism. Especially if the latter is not the lone gun it appears to be at first sight, but is an entire battery of cannons. This is why the story of the targetted assassinations of Karnataka’s public intellectuals, Gauri Lankesh and MM Kalburgi, is also the story of the people who are stepping forward to continue their unfinished work.

The things that made both Lankesh and Kalburgi see red were the same. A former vice-chancellor of Hampi University, Kalburgi, till the time he was silenced, was researching the irrationalities in Hindu religion, the unequal caste system that exists to perpetuate the dominance of upper castes, and the need to smash them. Kalburgi was also a litterateur. He was, therefore, somebody who was invited to speak at diverse fora and had a following. He was heard. Journalist Linganna Satyampet was a Lingayat like Kalburgi. A follower of Basavanna, that unorthodox 12th-century Brahmin who preached open revolt against Hinduism and its sacred texts and practices, Satyampet was murdered in 2012; Kalburgi in 2015. Like Kalburgi and Satyampet, Lankesh, a journalist, was a Hindutva critic and had lately developed a fatal flaw.

“Lankesh had spoken up about JNU, she was perceived to be pro-Maoist and she backed the separate religion demand too…this may have been the last straw,” says retired IAS officer SM Jamdar.

Kalburgi, on his part, had compiled 15 volumes of 12,000 pages of the work of Fa Gu Halkatti, an authority on Basavanna. “It sheds new light on the religion of the Lingayats, and on who we were,” says MB Patil, a prominent Lingayat minister in the Congress-led Karnataka government. Simply put, this research has been the engine that now drives the Lingayats’ demand to be recognised as a separate religious community. That has also meant that Lingayats like Kalburgi and Lankesh –– both of them backed the ‘separate religion’ demand –– have placed themselves in the line of fire from two quarters: the Hindu right, which finds their ‘separatism’ a threat and a challenge to its quest for political power, and certain sections of the Veerashaiva community.

The Veerashaiva-Lingayats are sociologically the same but with some differences in their beliefs and practice of ‘religion’. Basavanna’s was an anti-Brahminical movement, but it drew followers from all castes. Academics claim, Veerashaivas are the descendants of his upper-caste followers who, after his death, smuggled Vedic and Brahminical rituals, and worship of Hindu gods back into the faith that Basavanna had helped found.

For Lingayats, their relationship to Shiva, for example, is through the ishtalinga. The Shiva of the Lingayats is not the god that he is in the Brahminised Hindu pantheon. He is, instead, a symbol of anti-Brahminism, and the only deity they recognise. Lingayats follow no ritual in death or marriage, which Veerashaivas, in their affinity for Hinduism, do.

Kalburgi’s research was a reminder of these differences. The prominence of Veerashaivas is at stake if the separate religion project goes through, admits some Veerashaiva community members. “It would also divide the Hindu vote. Veerashaivism is Brahminical. Veerashaivism is about coming back to Hindutva,” says Patil.

To understand the issue that is roiling Karnataka today, as the state shifts gears to move towards assembly elections in early 2018 (the BJP has announced BS Yeddyurappa as its chief ministerial candidate), and how its outcome may impact other neighbouring southern states with a Veerashaiva-Lingayat population, we need to know about three old men.

Spiritual heads

Three men are dear to the Veerashaiva-Lingayats and for conflicting reasons. Basavanna, born in the 12th century, was a Brahmin in the Lutheran mould calling for an end to Brahmin domination and ritualistic religion. Lingayats love him. Veerashaivas, the other unit of the community, love him too, but they love Renukacharya more. Renukacharya is said to have emerged from the tip of a shivalinga. And, most importantly, he was born 1,400 years ago, beating Basavanna by a straight 500 years in antiquity. This one-upmanship seems to have been a friendly match till the Karnataka government, on receiving petitions from the community this April to move the Centre yet again for a separate religion status, placed a ringer around the subject –– should the religion be called Lingayat or Veerashaiva-Lingayat? And the questions the community had not asked itself for years, swiftly acquired a new force and meaning.

Veerashaivas are talking up “hurt” and saying that “this will split the community”. Lingayats see it as an opportunity to correct “historical blunders”. The latter say that Kumaramangalaswamy, the third old dear, despite being a Lingayat, founded the community organisation in 1904 and called it the Veerashaiva Mahasabha to spite his own community for not making him the leader of a mutt. More than 100 years later, Lingayats feel it’s not too late to “claim” their inheritance.

A Lingayat leader of Belgaum in northern Karnataka, Shankranna, has, in fact, been sacked, along with the entire district unit of the Veerashaiva Mahasabha, for putting forth a proposal to start a separate Lingayat Mahasabha. He says the movement will now see no let-up. “We are planning huge rallies in Vijaypura (on October 19) and Bengaluru (on December 10).”

Shankaranna is not an isolated case. Lingayat separatism now has important backers. All political parties seem interested in the idea even though they are unsure whether they should stake their entire reputations on it. Those from the Congress who are active on this ‘separate religion’ issue -- there are difference in nuances in their demands (see box ) -- are ministers such as MB Patil, Sharan Prakash Patil, Eshwar Khandre, SS Mallikarjun, Vinay Kulkarni, Mohan Kumari; from Janata Dal (Secular) it’s Basavaraj Horatti. BJP’s Yeddyurappa, a former chief minister and a Lingayat himself, too had earlier signed a petition asking for a separate religion but is now silent on the issue. The decision to have him contest from a north Karnataka seat, the hub of the Lingayat demand to be recognised as a separate religion, indicates the party’s recognition of this as a crucial poll issue. Will Yeddyurappa get the vote this time too?

Battle of ideas

In the 2018 assembly polls, a divided Veerashaiva-Lingayat community will confront difficult choices – should it vote for a fellow Lingayat or go with the spirit of Basavanna? The BJP with Hindutva as its political agenda runs counter to the essence of Lingayatism, hence, Basavanna. But does that mean the Congress or the JD (S) can be the party of Basavanna? That Kannadigas are now seeing the election as a battle of ideas is due to the ground laid by the work and lives of intellectuals such as Kalburgi and Lankesh.

HM Renuka Prasanna, the All India Veerashaiva Mahasabha secretary, says Kalburgi’s momentous work on the seers of the religion and their Vachanas – the prose-poems of Basavanna’s followers ranging from the weaver and the cobbler, to the town crier and the prostitute – has brought to the fore the openness, and the pragmatic and radical nature of this indigenous spiritual tradition.

Jamdar, now secretary of the Lingayat Horatta Samiti formed three months ago, explains it thus: “We are not Hindus. We Lingayats have a better tradition. The Right is more rattled if you challenge it in the name of an indigenous and older religion. Its proponents can’t say we came from ‘outside’. Basavanna said earn what you need, eat what you require. You could say we are the old Left. Our humanist philosophy predates Marx. Even the rationalists support Basava. Ours is actually a demand for recognition of our old religion. Vested interests are trying to diminish our stand by emphasising the separateness angle.”

His religion, he says, is 900 years old, older than the time Sikhism has spent in this country. “The RSS”, he adds, “wants a Hindu Rashtra. By propping up Veerashaivas, they feel Veerashaivas will do that job for them.”

There is, however, no clean break-up of political loyalties. Shankranna, a Lingayat, is a BJP man. He, however, feels the Karnataka chief minister did “great by installing Basavanna’s photo in all government offices next to those of Ambedkar and Gandhi, which none of the BJP CMs, Yeddyurappa or Jagadish Shettar, did”. Some members of the Veerashaiva community, on the other hand, such as Mahadevappa, a teacher at Tumkur, says that while he is “uncomfortable with the BJP’s Hindutva project”, he notes the Congress’s “preference for non-Veerashaiva-Lingayat chief ministers.” Lokesh, a Veerashaiva social activist from Mysuru, says his personal preference is for keeping the community united, and support the demand for a separate religion. He doesn’t want to “talk politics”.

‘The main thing’

MB Patil says his campaign is neither about dividing the community nor about “throwing the Veerashaivas out”; it’s about a rational way of sharing socio-economic power. “Veerashaivas joined the Lingayats instead of the other way around…. Adding Veerashaiva to our identity has been a blunder. It makes us seem aligned to Hindus and weakens our case for a separate religion. Veerashaivism is part of us but it is not the main thing. The community should unite under the Lingayat banner.”

Professor HS Shiva Prakash, author of the acclaimed play Mahachaitra, which draws on the historical and legendary aspects of Basavanna’s life, says the birth of the religion was a political act. So is the present demand for a separate religion from which socio-economic benefits are expected to flow.

Prasanna, the Mahasabha secretary, says the community should stay united and tackle more urgent worries.

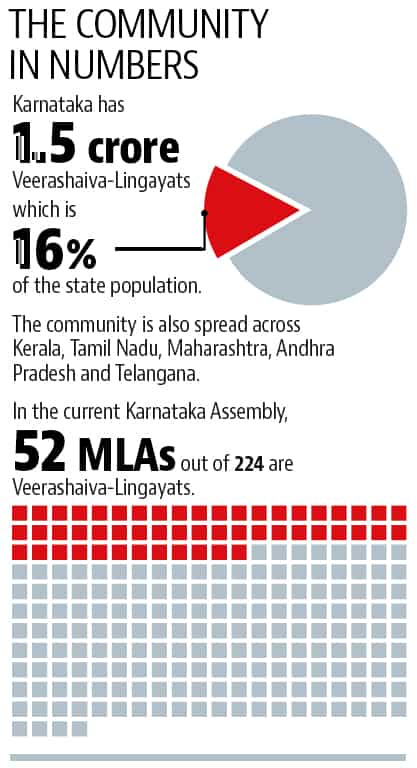

The Veerashaiva-Lingayat community is listed in the state’s Other Backward Classes category. Prasanna says the last two Census reports show the growth rate of the community’s population has remained static at 16%. “This is just not possible. It means people are not identifying themselves as Veerashaiva-Lingayats but as other OBCs who get more by way of government benefits and reservations.

“In Karnataka, reservation for our community is just 5%, which we share with some other castes, and certain traditional occupational groups within Christians and Jains. The fulfilment of our separate religion demand will get us minority status like that of the Jains, Christians, Buddhists, Sikhs and Muslims. [As minority religious communities they are not entitled to reservation but some sections from these communities get reservation because they belong to certain occupationally backward groups.]

“This will ensure we become eligible for other socio-economic benefits from the government, over and above the quota we already have.” says Prasanna.

A few minutes later, Shiva Kumbhar (name changed, not the surname), a student, lands up at Prasanna’s office. His case seems to prove Prasanna’s point.

Shiva is a Lingayat Kumbhar. But there are non-Lingayat Kumbhars as well who constitute another backward sub-caste, which has 15% reservation earmarked for it at the state level. For that reason, Shiva has tried to pass off as a non-Lingayat Kumbhar but now approaches Prasanna for accommodation in Veerashaiva-Lingayat-only hostels by owning up as a member of the community.

The recent demand that the community be recognised as a separate minority religious denomination will, according to Prasanna, change the contours of the Veerashaiva-Lingayat community. Pointing to the framed portraits of Renukacharya and Basavanna hanging close to each other in the Mahasabha’s office, he says in half-jest: “We don’t want Basava and Renukacharya to quarrel. This is why we always keep a picture of Hangalakumaraswamy in the middle.”

As we leave Bengaluru, the irony of the situation strikes us: a people fighting for an organised religion when the man who had initiated their movement had said there was need for none. The other side of the coin: the movement to institutionalise Basavanna’s cult could thwart the advance of the Hindu right-wing in the south.