Hindustan Times and the Mahatma

When Gandhi inaugurated the Hindustan Times press in 1924, he knew it was time for a paper that reflected sentiments and the shared national agenda of Indians

[In 2019, Hindustan Times marked Mahatma Gandhi’s 150th year with a special series comprising reportage, invited columns, essays and archival material. On the occasion of the Mahatma’s birth anniversary on October 2, this article has been published from a curated selection of our coverage.]

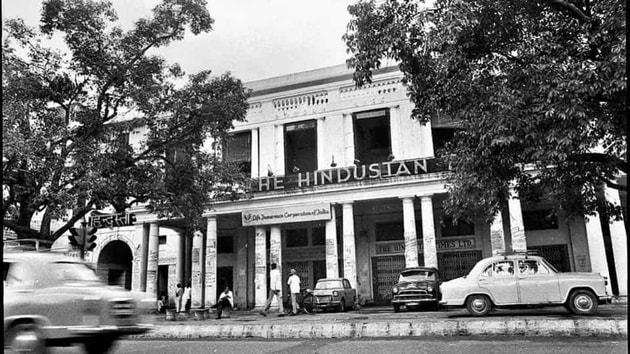

It was a sunny day in Delhi on September 15, 1924. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, who usually didn’t like giving speeches, stood in front of a three-storey building in a grain market on what was then called Burn Bastion road, not far from the Old Delhi Railway Station. Inside it, a Dawson Payne Hand Fed Stop Cylinder Press and a Miele Press — the only makes available in Delhi at the time — were crammed into two rooms measuring 24 feet by 24 feet on the ground floor. The top two floors had wooden benches and chairs. The Mahatma then proceeded to inaugurate the Hindustan Times press.

Gandhi, who was himself the editor of an English daily, Young India, and a Gujarati weekly, Navjivan, started off by saying that under the present conditions in the country, he would stop the printing of all newspapers except Young India, if he could. He hoped that the paper would prove worthy of the responsible profession, conducted with truth, tact and fearlessness. “Every word and sentence published in the paper should be weighed. There should not only be no untrue statements, but no suggestio falsi or suppressio veri,” he advised the small group gathered. Eight days later, the first edition was taken out, painstakingly, hand-pressing each letter in place.

Also watch| ‘Thud of falling newspapers was like lullaby’: Tara Gandhi on family’s association with HT

Gandhi set the agenda for the Hindustan Times, started by the Akalis with an initial investment of ₹25,000. He was also instrumental in getting K.M. Pannikar, a university professor, to become editor. However, within six months, freedom fighter Madan Mohan Malaviya bought the newspaper and by 1927, Hindustan Times was incorporated as a joint stock company, with Ghanshyam Das Birla as one of its biggest shareholders. Gandhi and GD Birla were also close associates, with the former staying often at Birla House. On January 30, 1948, he was assassinated there.

Gandhi was not cracking a joke when he expressed his disenchantment with the press at the inauguration. In a Navjivan piece, published in April 1924, he wrote, “Dr. (MA) Ansari [a Congressman] writes to say that those [north Indian] papers regard it as their duty to make allegations against each other, to spread false rumours, to calumniate each other’s religion and thereby to vilify each other. It seems this has become a means of increasing the circulation of their papers. How to stop this infection from spreading has become a big problem.”

Also Read: A city that nurtured a young Mahatma

Other newspapers, like The Statesman and The Times of India certainly had more capital; they were also English-owned, and often toed the imperial line. Thus, a paper that would reflect back to the reader her own fervour and sentiment was the need of the hour. Gandhi could not have been more correct. “Hindustan Times’ association with Mahatma Gandhi went beyond the circumstances of its founding and Devadas Gandhi’s editorship of the paper. It involved a shared national agenda and at the time, the only national agenda was freedom,” said Shobhana Bhartia, chairperson and group editorial director of HT Media Ltd, which publishes Hindustan Times.

The 1920s began on a sombre note. On April 13, 1919, General Dyer had ordered his troop to fire on unarmed protesters gathered in Jallianwalla Bagh in Amritsar. The news of the firing only trickled out of the Punjab town two months later. To date, the number of casualties remains contested. Then, in 1920, Gandhi had begun what he called the Harijan tour — an all India journey — to spread the word about abolishing untouchability. He also became increasingly concerned with the Khilafat movement, which Muslim leaders like Shaukat Ali, Mohammad Ali and MA Ansari, were involved in, over reinstating the Caliphate in Turkey after the First World War. Hindus and Muslims together protested against the Rowlatt Act, which sought to detain political prisoners without trial. Then, in 1921, Gandhi and the Indian National Congress called for a Non Cooperation movement to ensure swaraj, or self-rule, thus igniting a nationwide protest that involved making bonfires of foreign made goods.

In 1924, around the same time that the printing press of the Hindustan Times first cranked into motion, a small temple town called Vaikom in what was then the princely state of Travancore, was witnessing its own upheaval — those belonging to lower castes were prevented from entering the temple, or even walking on the roads outside it. The protesters adopted Gandhi’s satyagraha methods — courting arrest, fasting, non violent resistance — to protest this form of untouchability.

For Gandhi, nation building was as much about Hindu-Muslim unity, as it was about social reform within communities. A newspaper was needed that would not only reflect history in the making, but also the people — the common men and women — making it.

By the 1930s, as Krishna Kumar Birla writes in his autobiography, Brushes with History, his father, GD Birla, had taken complete charge of the paper. In 1937, GD Birla appointed Devadas Gandhi, the Mahatma’s fourth son, as editor. Devadas would go on to be the paper’s longest-serving managing editor. His term ended only with his death in 1957.

As with the Mahatma, the going was not easy for Hindustan Times. A 1903 Press Ordinance gave the British the right to confiscate the press, and seize property. Hindustan Times was called upon to furnish “securities of five, ten, and twenty thousand rupees (equivalent to ten, twenty and forty lakhs of rupees today,” JN Sahni, one of the earliest editors of the paper, wrote in his 1971 autobiography, The Lid Off: Fifty Years of Indian Politics 1921-1971.

Also Read: Gandhi’s impact on the Tamil psyche

After Devadas became editor, the alignment of Hindustan Times with the national struggle became more pronounced. “So great was the involvement of Devadas Gandhi’s family with the Hindustan Times that whenever the rotary press fell silent, I would wake up,” wrote Rajmohan Gandhi about his father, Devadas, in an article titled, My Father’s Father. It was Devadas who oversaw the buying of the land on which the current office still stands.

The late KK Birla, who joined the board of Hindustan Times in 1957, wrote in the foreword to 75 Years of the Hindustan Times: History in the Making, “A newspaper may be a business, but the Hindustan Times has always been a crusade.”

Devadas personified this. After Hindustan Times published an article in 1941 over judicial impropriety — the chief justice of the Allahabad High Court had reportedly asked judicial officers to contribute to the Second World War fund started by the government — the paper was hauled up for contempt of court. Devadas went to prison too, on a matter of principle.

When the Quit India movement had been launched, the paper shut down for over four months to protest against the censorship on headlines that the British had imposed on all newspapers. Yet, the paper itself was doing better than it ever had. In 1944-45, the paper declared a dividend to its shareholders for the first time. “Devadas celebrated this by promptly raising the salaries of his staff and hiring more,” former editor, Prem Shankar Jha, wrote in 75 Years of the Hindustan Times.

The paper published many pieces by Mahatma Gandhi through the 1930s and 1940s, on a range of subjects. In February 1943, when the British released a pamphlet, Congress responsibility for the Disturbances, 1942-43, over the 1942 Quit India resolution, Gandhi — then imprisoned at the Aga Khan palace in Poona — responded with a letter, several pages long and exhaustive in its defence of the call for political freedom. The letter was published in seven instalments in the Hindustan Times.

“My chief purpose is to carry conviction to the Government that the indictment contains no proof of the allegations against the Congress and me. The Government knows that the public in India seems to have distrusted the indictment and regarded it as designed for foreign propaganda,” Gandhi wrote.

Not only did the Mahatma know the pulse of the nation, but the paper that he inaugurated made sure that India was reading each word.

It still does.