Heroes of our time: Meet Indians making a difference

You’ve seen the pictures. You’ve heard the names. Read on to see what some of the winners who have largely remained away from the spotlight achieved and how

In times of bad news — disaster and distress in Chennai, smog in Delhi, the Yamuna covered in toxic foam — the Padma Shri awards handed out this week were a reminder, even in such an age, of the power of one. On the list were people who picked a mighty mission and persevered with it. You’ve seen the pictures. You’ve heard the names. Read on to see what some of the winners who have largely remained away from the spotlight achieved and how

Jaswantiben Popat, Maharashtra - A cracking good success story

You may not know her name, but you will definitely have heard of her brand.

Jaswantiben Popat, 94, is one of the seven co-founders (and the only surviving one) of Lijjat Papad. These women struggled together, 62 years ago, to set up Shri Mahila Udyog Lijjat Papad, which now employs 43,000 women.

On Monday, when the Padma Shri so lifted her spirits, she missed her sisters , her grandson’s wife Nitu Popat told HT. “She always says, they are not employees, all women working at Lijjat Papad are owners.”

Nitu says the seven women started out with ₹80 in capital. Once all their housework was done, they would gather on a building terrace in south Mumbai, knead the dough for their papads, and lay it out in discs to dry. Their product was so good, it grew organically into a company larger than they could have imagined, helping thousands more women gain some measure of independence.

“Jaswantiben still visits the Girgaum branch and attends meetings,” says Ramnik Nathwani, the company’s public relations officer.

Crafting healthier rice, wheat - Chintala Venkat Reddy, Telangana

He was going to meet the President and Prime Minister at Rashtrapati Bhavan! That was Chintala Venkat Reddy’s first thought when he heard that he had been awarded a Padma Shri.

Reddy, 71 and based in Hyderabad, is India’s first independent farmer to receive an international patent. In February this year, he patented his innovation for producing foodgrains (particularly the widely consumed rice and wheat) that are enriched naturally with Vitamin D, making them more nutritious. He also secured another international patent for his technique in soil swapping to improve soil fertility.

A farmer who opted out of formal education in Class 11, Reddy has worked his marvels through painstaking experiments conducted, over 10 years, in his own fields at Alwal in Telangana. He used various nutrient-enhancing compositions such as carrot extract, maize flour and sweet potato extract, which increase Vitamin D content in plants when applied during irrigation. In some cases, the seed of the crop must also be soaked in these extracts before sowing.

Already, private seed companies have approached him, he says. But Reddy does not want his work commercialised.

“These awards and appreciations give me immense satisfaction. But the real satisfaction will come when people across the country benefit from my work,” he says. “If the Indian government can take this technology into fields, India can export grain enriched with Vitamin D to the world.”

The seed saver - Rahibai Popere, Maharashtra

When her grandson kept falling ill as a child, Rahibai Popere decided to trace the problem to its roots. “I realised we had to resume organic farming,” she says. “It is at that point that I started conserving indigenous seeds.”

That was 21 years ago. Since then, Popere, 57, a farmer and mother of four, has created a seed bank of 154 varieties of native grains and vegetables in her village of Kombhalne, in Ahmednagar, Maharashtra.

Initially, people made fun of her, she says. “I had to convince people that what I was doing had value. My home was small and I didn’t have proper space for my conserved seeds. There was a time when I used to cry at night, but in the morning I resumed work.”

At social gatherings, she would gift saplings to other women. She reached out through NGOs and self-help groups. Her mission is healthy eating, conservation of indigenous foods, and revival of crop diversity.

“Now my work has reached many and I get invitations to speak or people visit my home,” says Popere, speaking over phone from Delhi where she received the Padma Shri on Monday. Anyone who comes her way leaves with lessons in organic farming, biodiversity and wild food resources.

Her efforts are now supported by the Pune-based BAIF Development Research Foundation, a non-profit that has set up seed banks in Palghar and Nandurbar districts. Thousands have availed of seeds from the collections traceable back to Popere.

Her village, meanwhile, still has no good roads and sporadic water supply. This came up in her brief interaction with Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

“I have invited Modiji to my village,” she says.

A hero who rose from tragedy in Bhopal - Abdul Jabbar, Madhya Pradesh

For Abdul Jabbar, as for so many others, the Bhopal gas tragedy never ended.

Until his death in 2019, aged 62, Jabbar fought to help those who suffered health crises and were denied compensation after breathing in the toxic gases released during an accident at the Union Carbide factory in Bhopal in 1984. He has now received the Padma Shri posthumously; his wife Saira Bano accepted it on his behalf.

Jabbar was 27 and lived 1 km from the site at the time of the disaster. After rushing his mother and brother to safety, he returned to save others.

Jabbar lost his mother and brother that night. He lost 50% vision; he would struggle with heart and lung conditions for life. But he worked in the area for 15 days without a break. His work would continue long after.

Jabbar fought Union Carbide for compensation in street protests and in court. He fought to have the definitions of who was eligible for compensation expanded to include, for instance, widows and daughters of men who died.

He launched an NGO and a vocational training centre where trainers taught women to use computers and stitch clothes. He rushed people to hospital himself, when the effects of the gas tragedy surfaced, sometimes decades later, in horrific ways.

“The people respected Jabbarji because he was a most honest activist,” says activist Rachna Dhingra. “Even the officials respected him. He always turned up if someone was in trouble. He never stopped working for the people.”

No tusk too daunting for the elephant doctor - Kushal Konwar Sarma, Assam

As a child, Kushal Konwar Sarma was often scolded for abandoning his homework to spend time with Lakhi, an elephant who lived with the family for part of the year, in Barama village, Assam.

It was his love for Lakhi, though, that led to him becoming a veterinarian, then a veterinary surgeon.

Decades later, elephants are now legitimately his life. He’s known across the state as the elephant doctor, and was recently awarded the Padma Shri for his efforts to save the lives of pachyderms in the wild.

“I was always very comfortable with domestic elephants, but I felt I could get close to wild ones too. In 37 years, I’ve treated other animals, but my priority is always pachyderms,” says Sarma, 60, now also a professor and head of surgery and radiology at the College of Veterinary Science in Guwahati.

Sarma has performed an estimated 2,000 surgeries on elephants so far, and treats about 700 a year. He also works with NGOs to educate people about non-violent ways of dealing with human-elephant conflict, a big problem in Assam.

“I’ve known Sarma for nearly 30 years. Despite his vast experience, he treats every new case with a fresh outlook and is always sincere,” said Bibhab Talukdar, who heads the wildlife NGO Aaranyak.

“His involvement was key in translocating 22 rhinos from Kaziranga National Park and the Pobitora Wildlife Sanctuary. The Padma Shri honour to him is very well-deserved.”

Even on his visit to Delhi, he ended up rolling up his sleeves. A pachyderm at the zoo needed its tusks removed. One of Sarma’s former students Abhijit Bhawal, now chief veterinarian there, called and asked if he could help.

“He’s a very busy man but he’s always full of enthusiasm to work with elephants,” says Rathin Barman, joint director of the conservation NGO Wildlife Trust of India.

Finding new life, dancing to a new tune - Manjamma Jogati, Karnataka

When Manjamma Jogati, 64, walked past Prime Minister Narendra Modi and other dignitaries towards Indian president Ramnath Kovind on Monday, it was already one of the most iconic moments for her community. Then, she stood before the President and blessed him by holding the fringe of her sari over his head. A community long shunned and relegated to the margins was at centrestage.

Manjamma Jogati was born biologically male in mineral-rich Ballari, to parents who were so concerned that she “acted like a girl” that they tried a range of offerings and rituals to “cure” her. Distraught, she attempted suicide in her teens. When she survived, she was told to leave the house.

On the streets of Ballari, alone, she saw a young man dance with a deity on his shoulders. That was what she wanted, she realised. To be free, to perform, to be her true self.

She made her way to Kolar in southern Karnataka, where she worked at a small restaurant. She met Kaalavva Jogatti, from whom she learnt the art of Jogati, a ritual folk dance in Karnataka performed by members of the Jogappa transgender community in Karnataka.

The Jogappa is a tradition of gender-fluid holy women who are born biologically male and believed to be possessed by the goddess Yellamma. They are seen by devotees as a special link with the goddess.

Manjamma Jogati now began performing as part of Kaalavva Jogatti’s troupe. Eventually, she took over the troupe when her guru died. In 2019, she became the first transgender person to be appointed president of the Karnataka Janapada Academy, set up to promote folk art in the state.

Manjamma was awarded the Padma Shri for her contribution to the arts. But her success also throws light on a community of people still compelled to beg on streets or forced into sex work because most means of employment remain closed to them.

That struggle continues. “You can give the Bharat Ratna, Padma Vibhushan, Padma Bhushan, Padma Shri, but how do we change mindsets,” says transgender activist Akkai Padmashali. The government needs to act to recognise and protect the rights of the transgender community, Padmashali adds.

A school from oranges - Harekala Hajabba, Karnataka

Sometime in the late 1970s, a tourist walked up to Harekala Hajabba and asked the price of his oranges. He sat and gaped, not understanding a word. The foreigner tried again, but of course that didn’t help. A passerby explained what was being asked.

On his way home, Hajabba told himself this shouldn’t happen to his children, or any children. There was no school in Hajabba’s village of Harekala-Newpadpu, and therefore no place to learn English. He decided he would change that. It was an impossible dream, given that he was earning about ₹80 a day from the orange stall at the time, but he began to save up.

“My wife would ask me how many years it would take to build a school with little money I was saving. But however long it took, I wanted to build that school,” he says.

It took Hajabba more than two decades. The Harekala-Newpadpu village school opened to students on June 17, 2000. Government funding has provided a boost and a high school section was opened in 2007. From 28 students, it now accommodates a total of 175, all the way to Class 10.

Hajabba, now 66, feels that more than his savings it was his perseverance that realised the dream. “I knew that it would be difficult to do it on my own, so I went to a lot of people asking for help. In most of the cases, they came forward when I told them what I was doing.”

His Padma Shri, he says, he merely received on behalf of his village and all those who made the school possible. “I’m just an orange seller. I can’t say that I built that school because it is not possible to build a school with the savings I had. The school was built because so many people donated,” he says.

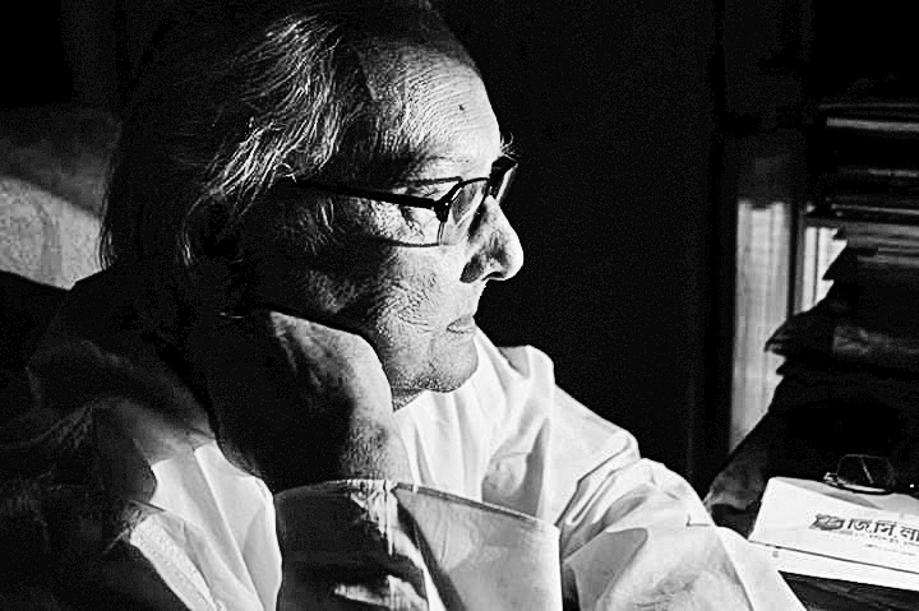

The making of a superhero - Narayan Debnath, West Bengal

In a time of strife, he gave the nation a cheery superhero. Legendary comic creator Narayan Debnath, 97, received a Padma Shri this year, for his artistry and for the joy his work has brought to generations of Indians. He created the long-running and much-loved Bengali comic series Handa Bhonda in 1962. It followed the adventures of two mischievous boys and their bad-tempered uncle.

Then, during the 1965 India-Pakistan war, he created Bantul The Great, a man of extraordinary power. Bullets bounced off him; he could not be defeated. The ongoing war featured in the comics too; Bantul chased away Pakistani tanks and brought down fighter jets with a lasso.

Today, Debnath can’t hear very well. “Sometimes he speaks very softly and incoherently. He is bedridden,” says his youngest son Tapas Debnath, 55. His work still speaks. It tells tale of a simpler time when fun was an afternoon annoying the neighours, and when all of India came together in times of trouble.

Debnath created other characters too, a detective, an adventurer; he wrote horror tales too.

Born and raised in Howrah, West Bengal, his family ran a business detailing gold jewellery, but he only ever wanted to draw. His talent was not formally schooled; Debnath signed up for an art degree but did not complete it. The love he had for pencil and ink never waned. He was drawing until as recently as three years ago, his son says.