Has GST been inflationary for India?

There are two ways in which GST could have caused a spike in inflation: by raising the rate of tax on goods and services, and bringing within its coverage business activities outside the tax net earlier.

With the first anniversary of the implementation of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) coming up, it makes sense to ask the question. After all, the government went out of its way to make sure this wouldn’t happen, even setting up a watchdog to ensure companies didn’t use GST as an excuse to raise prices.

The short answer is that we still don’t know for sure.

The long answer, however, is more interesting, because it highlights the pulls and pressures on the economy over the past year.

Annual growth in the 2012 series of Consumer Price Index (CPI), India’s benchmark inflation measure, was the slowest (1.46%) in June 2017. India implemented GST in July 2017. The inflation cycle turned from July 2017 and annual growth in CPI reached a 17-month high of 5.21% in December 2017. It has continued to hover above the 4% mark in the subsequent period. Purely based on numbers, GST seems to have had an inflationary impact on India.

There are two ways in which GST could have caused a spike in inflation: by raising the rate of tax on goods and services, and bringing within its coverage business activities outside the tax net earlier. The latter would push up inflation as any tax incidence on such businesses is bound to be passed on to consumers in terms of higher prices. In a country like India, with a huge informal sector, successful implementation of GST may have brought a lot of non-tax paying firms and transactions under the tax net.

After the implementation of GST, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) had ruled out any significant inflationary impact due to an increase in taxes due to two reasons: a large number of items in the CPI basket were exempted from GST, and the effect of a rise in the tax rate on some items was compensated for by a fall in the rate on other items.

GST’s inflationary impact due to expansion of the tax net is a more difficult thing to estimate, although, if the government knew beforehand who was evading how much in tax, it would have forced them to pay taxes anyway. Even after the implementation of GST, key commodities such as petroleum and alcoholic beverages are outside the GST net. Also, GST is not the only factor which is likely to be influencing inflation at any given point of time.

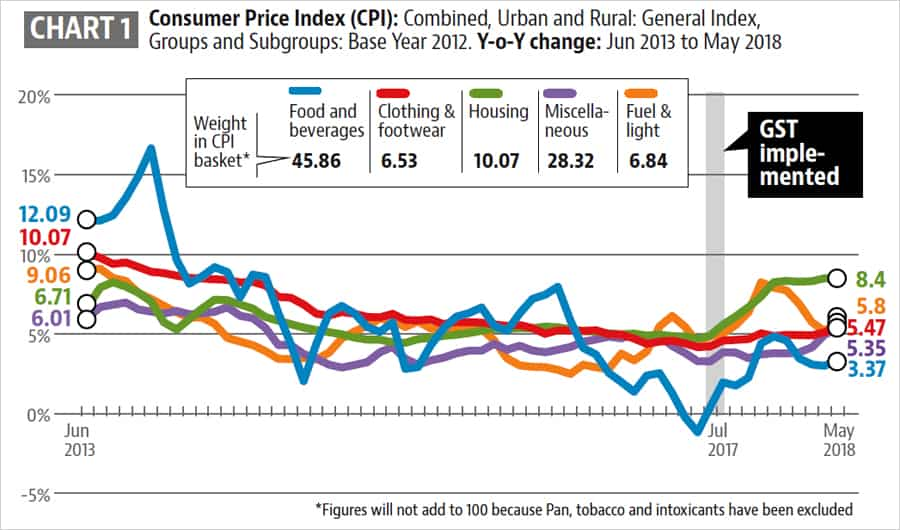

With these caveats in place, it is worth looking at the trends in inflation and inflationary expectations after the implementation of GST. Chart 1 shows annual growth in various sub-components of CPI. Except fuel and light, which had reversed its declining trend in 2016 itself, all other sub-components show a trend reversal in or immediately after July 2017, the month when GST was implemented. It is worth noting that other sub-components of CPI were not rising between August 2016 and June 2017, even though the fuel component of CPI had already started increasing. (Chart 1 here)

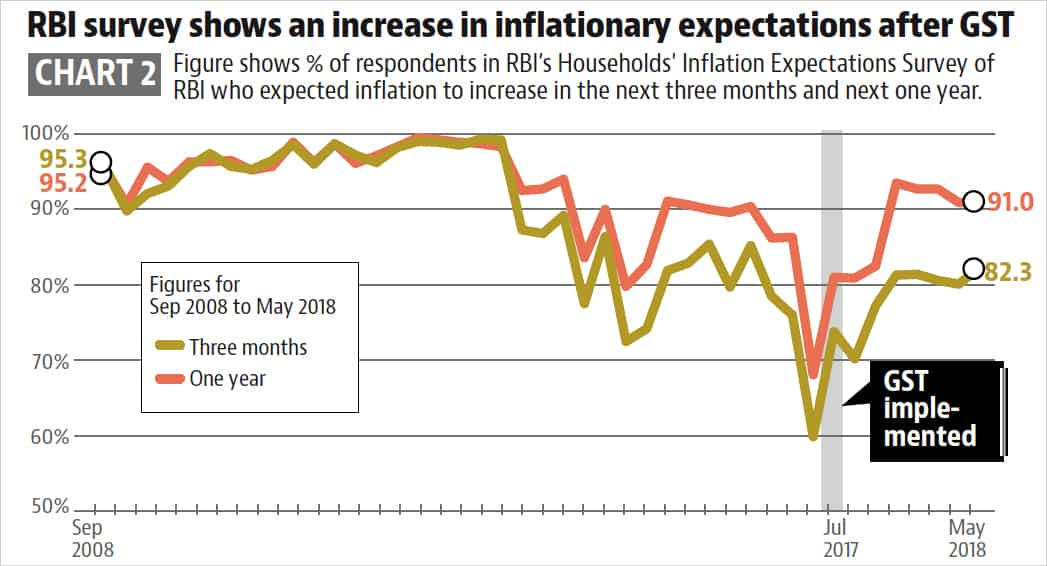

A similar pattern can be seen in inflation expectations also. RBI’s consumer confidence survey seeks responses about their expectations about inflation increasing in the next three months and one year. Between June 2017 and September 2017, the interval which corresponds to implementation of GST, the rise (between two consecutive surveys) in the number of respondents who thought inflation would increase in the next year was the second highest since December 2008. The highest figure is for the period between December 2016 and March 2017, which was probably due to the disruption caused by demonetisation. (Chart 2 here)

What is also interesting is that the difference between share of respondents who saw inflation rising in the next three months and next year was the highest since September 2008 in September 2017. One can assume that expectations of inflation rising in the next one year are driven more by structural factors (such as GST) than seasonal factors, which are more likely to influence expectations about inflation in the next quarter. The numbers also show that the gap between respondents who expect inflation to increase in the next year and next three months has continued to remain high in the post-GST period. The average value was 3.5 between September 2008 and June 2017, but it has increased to 11 between September 2017 and May 2018.

But this could be mere correlation, not causation.

Do these numbers offer conclusive proof that GST has had an inflationary impact on the Indian economy? Experts call for caution. Rise in petroleum prices and increase in house rent allowances under the 7th Pay Commission, both of which are not related to GST, might have contributed to the rise in CPI in the post-GST period, said Himanshu, an associate professor of economics at Jawaharlal Nehru University.

Fuel prices have a cascading effect and could have resulted in higher prices of several products. While it is true that GST might have had a cost-push inflationary impact due to passing of taxes, its overall contribution to inflation growth might have been subdued due to erosion in demand because of small businesses coming under strain due to implementation of GST and rural distress in the economy. It is only when these factors dissipate that we will know the answer for sure, Himanshu added.