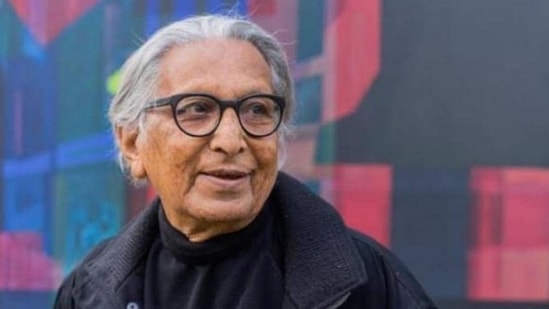

Doshi, a pioneer who opened the doors for Indian architecture

My introduction to BV Doshi was through my father, Umakant Oak, also an architect and Doshi’s classmate in NMV School, Pune

My introduction to BV Doshi was through my father, Umakant Oak, also an architect and Doshi’s classmate in NMV School, Pune. When I was scouting for architectural schools, my father asked me to apply to Prof Doshi’s school — School of Architecture in Ahmedabad.

I landed at the school, and was pleasantly surprised by the wonderful atmosphere there. We were just 30 in class, that helped keep us close to him. Doshi wanted to expose us not just to architecture, but to Indian culture, music, and our rich heritage. He wanted us to be in tune with our environment, hand in hand with age-old crafts, music, and various other art forms.

Doshi used to get architects and other eminent personalities from all over the world to the school – he was abreast of not only what was going on in India but also across the world; he was, after all, the protégé of Le Corbusier.

Doshi’s institution was the expression of a visionary. He wanted students to be exposed to all aspects of design. He would even bring masons on campus and make us construct bricks for small projects. He said, when you go on site, you should know what needs to be done – you should know what to expect of a mason and a carpenter.

As students, we were immersed in his philosophy, his design, and his attention to detail. The School of Architecture was his pride and joy. It was unlike any other school – the environment was such that the students and faculty were closely connected. That was the intention in interconnecting the studios making sure that the students could work closely with each other. The school building was light and airy; it had windowsthat allowed the light to filter into the studios during the day, and there was very little of artificial lighting.

We are talking about sustainability today, but all that was built in the school design then. We did not require air-conditioning at all. Doshi put up huge load bearing structures in the east-west directions and kept the north-south open to allow breeze to flow in. There were beautiful views of the lawns from the classrooms and the studios.

The space just flowed from the basement upwards, and from one side to the other.

He also built the IIM Bangalore with the same philosophy. He believed that you learn not just in the classrooms but also in corridors, where most discussions take place.

Another project which expresses his vision is Vidhyadhar Nagar, a new township next to Jaipur, commissioned by the Jaipur Development Authority, in 1982. It was named after the architect of Jaipur itself, one of the most planned cities of India.

He derived his design from Jaipur to build the new city. He thought Jaipur had a character that was neither too overwhelming, nor too modern. He wanted to weave those elements here. Doshi believed there was much to learn from history, which had to be modified to the present context: after all, cities are meant for people, he would say.

Aranya, a housing project in Indore, built in the 1970s and 1980s was unique, as it was envisioned for the economically weaker sections (EWS). Up until then, the government could only think of giving a finished product to the citizens. But Doshi came up with a unique idea – he felt people were actually capable of building on their own. They only needed sites and services, which can be provided to them in terms of infrastructure, source of water and a sewage system.

With the help of local masons and people themselves, he made a library of different elements of a building. His idea was to make a material bank and let people decide what would work best for them. Their homes should not be an imposition on them, like the egg-crate architecture that have mushroomed all around us today.

After experts had put the basic structure in place, people were given room for expansion as well. They had the space to add rooms. They could choose what kind of staircase to build – spiral, ladder or L-shaped. He was letting them decide. It took around eight years to build.

As a young professional, I moved to New York for several years. Doshi stayed with me when he visited the city. He was a disciplined man – he would be up at 5:30am, do his pranayama and get the day started. He wore his fame easy – he did not wish to be called Doshi ji or Doshi saab; he communicated with every one as an ordinary person.

Apart from being meticulous about his work, he was a great lover of classical music, and would organise programmes at Sangadh. Architecture was in a box until now – he liberated it by letting diverse art forms influence him.

His Pritzker win in 2018 put India on the map in world architecture. Having worked in New York, I knew people in that city were not exposed to architecture in India. This recognition made him the most important person in architecture in India.

The passing of B V Doshi is indeed a great loss to the fraternity, nationally and internationally, and to me personally. We are still recovering from the shock.

(The writer is head of department of urban design programme, Aayojan School of Architecture and Design, Pune. He worked with B V Doshi soon after graduating from School of Architecture, Ahmedabad in 1982)

All Access.

One Subscription.

Get 360° coverage—from daily headlines

to 100 year archives.

HT App & Website