Covid-19: What you need to know today

Six months after the pandemic began (though the World Health Organization dragged its feet, declaring it as a pandemic only on March 11), it can be safely said that when it comes to Covid-19, there is no such thing as an exception. If the data is too good to be true, it probably isn’t true.

Data and science, I wrote in this column a few weeks ago, are the only two things needed to fight the coronavirus disease — and establishments around the world have always had an uneasy relationship with both.

I was reminded of this after The New York Times reported that the US federal government has ordered hospitals to stop sending Covid-19 patient information to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and instead send it to a central database. The piece added that “the move has alarmed health experts who fear that the data will be politicised or withheld from the public”.

Also read: Covid-19 rapid antigen tests high on accuracy, but protocols crucial

Around the world, governments and provincial and local administrations are being feted or faulted for the number of Covid-19 cases and the number of deaths in their countries, states, cities, even districts. This is understandable — the number of new cases and the spread of infections are directly related to how well administrations manage to enforce the wearing of masks and social distancing, and their effectiveness in testing and tracing; and the number of deaths depends on access to and quality of health care.

As the number of cases in the US rises (the average new cases for the past week was around 60,000 a day) in an election year, it is understandable that the Trump administration wants to control the data. Understandable, but still not correct.

Click here for complete coronavirus coverage

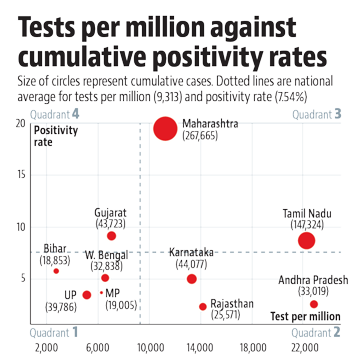

Closer home, states that aren’t testing enough are equally at fault. Among large states (with a population in excess of 50 million), the states that perform the worst in terms of number of people tested for Covid-19 for every million of the population are Bihar (2,737 per million), Uttar Pradesh (5,144 per million), Madhya Pradesh (6,344 per million), West Bengal (6,589 per million), and Gujarat (7,035 per million). The national average is 9,313, and all other states with a population in excess of 50 million test more than that. If the states don’t test enough, they won’t show enough cases, and the thinking is that this makes them look good. That it may — but only in the short-term.

Six months after the pandemic began (though the World Health Organization dragged its feet, declaring it as a pandemic only on March 11), and nearly four months after I started writing this column, it can be safely said that when it comes to Covid-19, there is no such thing as an exception. If the data is too good to be true, it probably isn’t true.

Every country, and every region within a country, invariably traverses the same trajectory of infections. It may not when it comes to deaths, because that is also a function of health care, and there may be other factors at play — such as the BCG vaccine, which research, including a very interesting Indian study, has shown to provide some kind of protection from Covid-19 (HT has reported this extensively).

Also read: 99 doctors have died fighting Covid 19, IMA sounds ‘Red Alert’

The only lucky break anyone can catch is probabilistic — the disease doesn’t infect everyone exposed to it, and everyone infected by it does not transmit it. All of this adds up to just one thing — if every state in India were to test at the same level, the number of infections they find per million of the population should fall within a range. If it doesn’t, there are other factors at play.

With deaths beginning to come under control across India, the two key parameters to watch are the tests per million and the positivity rate.

The chart accompanying this column shows how large states (population in excess of 50 million) perform when mapped against this — in a classic matrix of the kind that consultants love. States that are housed in the first quadrant (low testing and low positivity rate) are the ones India should be worrying about the most. States that are in the third quadrant (high testing and high positivity rate; Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra) will all eventually enter the fourth one (high testing and low positivity rate) signalling that they have travelled the course of the pandemic. The caveat (there is always one): it is important that states traverse the trajectory in terms of positivity rates as they increase testing. That means Rajasthan, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh, which are already in the fourth quadrant, have to be evaluated against this metric. It also means a weekly snapshot of average daily tests and average positivity rates may provide states with a good dashboard to measure their progress.