Constitution @ 70: A look at how citizens are reanimating its progressive ideals

As the Constitution completes 70 years, its stirring Preamble continues to inspire Indian citizens

On January 17, Chandrashekhar Azad, the charismatic Bhim Army chief, arrived at the Indian Women’s Press Corps in Delhi for a meet-the-Press event, holding a copy of the Constitution. In his opening statement, which included a measured reading of the Preamble in Hindi, Azad, sporting his trademark blue scarf, said, “If the Bharatiya Janata Party government believes that the Preamble is provocative, then I do not mind reading it again … The Constitution says it is the duty of every citizen to protect it... I am doing that,” said the Ambedkarite activist and lawyer.

The Constitution completes 70 years today. Cutting across religion, gender, age, and caste, people across the country have been celebrating the 117,369-word document — which broke the conventional thinking prevalent at the time of its creation — in a unique way, by making it the centrepiece of their protests against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA), the National Register of Citizens (NRC), and, of late, the National Population Register (NPR). The trinity, dissenters say, goes against the fundamental constitutional principles of secularism and equality. To be sure, the government has said that there is no immediate plan for an NRC.

From the steps of the Jama Masjid in Delhi, where on December 20, 2019, Azad held up the Constitution in one hand and a photo of BR Ambedkar in the other, to university campuses across the country, copies of the Constitution are being waved in the air, and the document is being celebrated for its progressive ideals.

In many places, such as Guwahati, citizens organised samvidhan (Constitution) sabhas; in other places, there have been well-attended marches, mass readings of the Preamble, accompanied by spirited renditions of the National Anthem, and the waving of the Tricolour.

WE, THE PEOPLE OF INDIA

It’s not difficult to see why the Constitution, especially the Preamble, resonates with citizens, and continues to play a strong role in political activism and public argument in this country.

“The life of the Constitution lies in the Preamble. As a statement of principles and beliefs, it works to give life to the legal language of the Constitution,” explains Alok Prasanna, senior resident fellow, and head of the Bengaluru office of the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy. “It is framed in such a manner that each generation finds new meanings in its depths to meet their own needs.”

Historian and lawyer Rohit De’s The People’s Constitution, he adds, shows that the Constitution was always owned by the people, and that it is not a document drafted by the elites for the people.

To many, the Constitution is a document of inspiration, and a means to transform society and the State-citizen relationship. “The provenance of the Constitution isn’t as foreign as some would like us to believe. It is an Indian document. It is a document that we’ve given to ourselves. To keep our democracy thriving, therefore, we need to reanimate the Constitution’s spirit,” says Suhrith Parthasarathy, an advocate practising at the Madras High Court. “When we see people waving it today, what we’re seeing is a reclaiming of its text and spirit”.

CITIZEN-CENTRIC

The Constitution, which lays down the governance structure of the State, procedures, powers, and duties of government institutions, and sets out fundamental rights, directive principles, and the duties of citizens, is one of the landmark constitutions of our time.

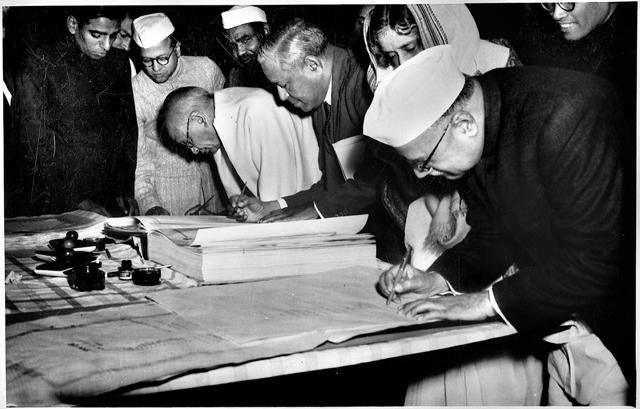

In 1946, 389 men and women from a variety of intellectual backgrounds, and holding different ideas about the new nation, came together to form the Constituent Assembly (CA).

The CA had a formidable task: Drafting a Constitution for a nation that was coming out of centuries of colonial rule, was poor and illiterate, riven by caste conflicts and religious and linguistic differences.

Yet, as legal scholar Madhav Khosla writes persuasively in The Indian Constitution, the Constitution’s creators decided that it should be a “decisive departure from the past.” The Constitution’s enumeration of rights, the granting of universal adult suffrage, finds no parallel in the colonial legal system. Importantly, Khosla adds, the CA was attentive to caste and religious identities, and also the rights of the regions, putting in place a federal State. “It was an extraordinary experiment in Indian history,” writes Khosla. Notably, despite the substantial presence of a single party in the CA (the Congress), the assembly was a body of remarkable intellectual diversity, and Jawaharlal Nehru must be celebrated for ensuring that.

While the document is loved by lawyers, they are not the custodians of the document; people are central to the Constitution, and are the real owners. “They [CA] believed in the possibility of creating democratic citizens through democratic politics,” Khosla writes in his latest book, India’s Founding Moment: The Constitution of a Most Surprising Democracy.

In that sense, the Constitution, lawyer Gautam Bhatia argues, was “transformative” too.

In his closing speech to the CA on November 25, 1949, its chairperson BR Ambedkar said: “Political democracy cannot last unless there lies at the base of it social democracy.” These words, Bhatia writes in The Transformative Constitution, distilled the heart and soul of the document: “Liberty, Equality and Fraternity were the three mutually reinforcing pillars.”

Thanks to these basic, universal ideals that the Constitution so well captured, the spirit and the values of the document have seeped into the crevices of India’s collective consciousness over the last 70 years, sometimes without citizens even realising it.

“Since the protests broke out and the State-led violence in my alma mater, I have been travelling to the poorest parts of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. The poor are at a loss to understand the CAA-NRC... they may not use not use the word samvidhan in their protests, but have internalised the Constitution’s values, and are aware about the rights that it provides them,” says Dr Maskoor Ahmad Usmani, former president, Aligarh Muslim University Students’ Union. “For the last 100 years, the farmers told me, they have provided food on the nation’s table without getting any land rights ... so why is the government now asking them to prove their citizenship?” Through these interactions, Usmani says he understood the “superior quality of the Constitution… its human values and ideals that are ensuring that these protests don’t turn violent”.

FOR THE APOLITICAL

The beauty of the Constitution is that its principles are not just spurring protests in expected political arenas, but also making the “apolitical” take a definite stand on the politics of the day.

“Our college has always stayed away from campus politics and protests. But this time we decided to join the protests because we want to reiterate that we still believe in constitutional values,” says Maitreyi Jha, a third-year BA Hons. (History) student at Delhi’s St Stephen’s College. “I think people are using the document to fight back, to highlight, and to remind the government that normalising a state of lawlessness and regular violation of rights doesn’t mean that people will forget the rights granted by the Constitution”.

The ongoing mobilisation and the re-reading of the Constitution could turn out to be a watershed moment for India.

“I don’t know what this movement will achieve; tomorrow Shaheen Bagh [a locality in south Delhi where citizens have been holding protests, seven days a week, 24 hours a day, for more than one month now] may die down, students will go back to classes, but India will never be the same again,” says Aman Wadud, a “citizen-lawyer” from Assam, where the first spark of protests against the citizenship law was lit.