A disaster in the making: How rising temperatures will affect India

The past decade has been the warmest since 1901 in India. Effects of rising temperatures will manifest in frequent and intense heat waves that will impact lives and livelihoods.

Weather data from over a century of record keeping, at the India Meteorological Department (IMD), captures an alarming warming trend that is having real impacts on people’s lives, experts warn.

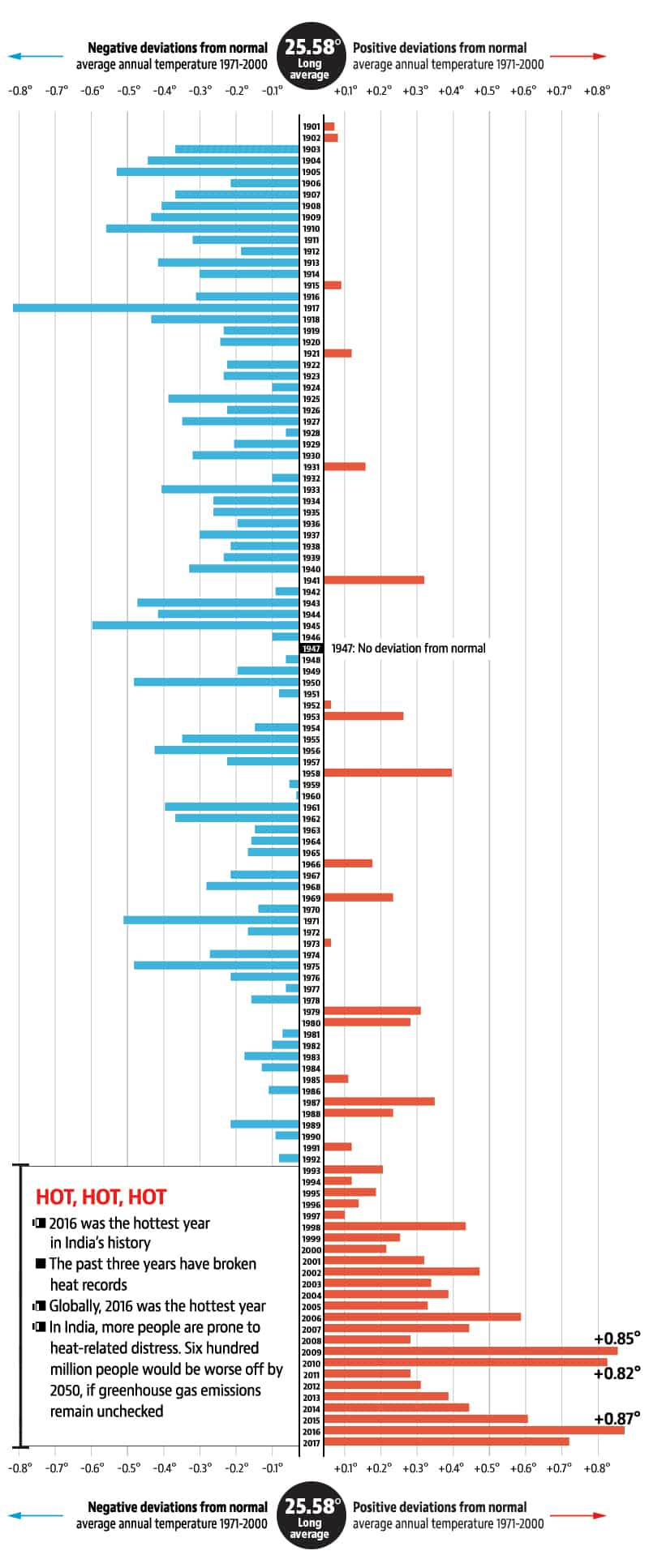

Not only have the last four years been record-breaking in terms of heat, the past decade has been the warmest since 1901, when record keeping started. Between then and now, annual average temperatures have risen by 0.66 degree Celsius every 100 years and maximum temperatures by 1 degree Celsius.

The rate of increase has been faster in recent decades. “The decade from 2008 to 2017 has been the warmest decade on record for India,” Arvind Srivastava, senior scientist at the climate monitoring and analysis division of the IMD, said, adding, “it was more than 0.5 degree Celsius above average.”

What is considered normal temperature today is an average of the annual temperatures for a 30-year period from 1971 to 2000.

It is pegged at 25.58 degrees Celsius. This ‘normal’ is due for an official update next year, Srivastava said, with data from the time period 1981 to 2010. The new normal: 25.77 degree Celsius, a 0.2 degree Celsius jump.

This increase may seem trivial, but benchmarked against 2 degrees Celsius, it is significant.

Under the Paris agreement, keeping average global temperature rise under 2 degrees Celsius by 2100 is essential, to avoid catastrophic effects for the planet.

If action to check climate change on the lines of the agreement is taken, India’s average annual temperatures could see an increase of around 1-2 degrees Celsius by 2050 but if no measures are taken this increase could be as much as 3 degrees Celsius, a recently released World Bank report, said.

‘Slow disasters’

The direct effects of rising temperatures will manifest not just in more intense and frequent heat waves, according to studies, but have more pervasive, long-term impacts that go beyond heat wave death tolls.

“Climate change induced environmental degradation, sea level rise; desertification and even drought are slow disasters,” an environment ministry report noted.

“These are considered disasters in the sense that they cause damage and disruption to human well being and the ecosystem.” The World Bank report warned that shifting average temperatures and changes in rainfall patterns would ultimately depress living standards across India, especially in the inland areas. There is an optimal temperature beyond which any increases in temperature lead to a fall in household consumption expenditure, used as a proxy for living standards.

India, according to the World Bank report, has already crossed that point.

“These changes are being driven by changes in average temperatures,” Muthukumara S Mani, lead economist for South Asia at the World Bank, said, adding that they “will result in lower per capita consumption levels that could further increase poverty and inequality in one of the poorest regions of the world, South Asia.”

Rise in average temperatures impinge on people’s lives in many ways: through adverse effects on health, uncertainty in agricultural production, forced migration and lower productivity, which all show up as decreases in basket of goods and services consumed by households.

Abnormal heat increases the chances of heat-related illnesses, fuels the spread of vector-borne diseases such as malaria, dengue and chikungunya, increasing the health expenses of households. Families that are heavily dependent on agriculture are at greatest risk, the report found.

“What is most challenging is the gradual change in temperature over the last 50-60 years and the changing precipitation patterns, these could have huge implications,” Mani said. “If you are a farmer even a 1 degree (Celsius) increase could make a huge difference in terms of what crop you can plant.”

Uneven impacts

India has consistently called attention to the injustice embedded in global climate negotiations against developing countries that historically contributed the least to carbon emissions but are likely to suffer the most from its impacts.

Of the 10 districts in India, likely to be impacted the most under the worst-case scenario, where no action is taken to check climate change, seven are in Maharashtra. These are concentrated in the Vidarbha region, where farmer distress is already very high.

In the rest of the country too, the impact of climate change will be disproportionately felt. Studies have shown that those areas that are most vulnerable to heat stress are characterised by low levels of urbanisation, literacy rates, poor access to water and sanitation and household amenities.