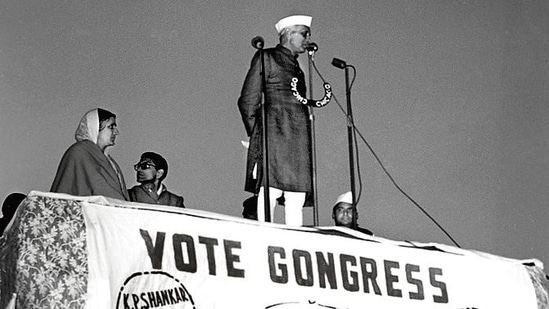

A commitment to the democratic ideals was Nehru’s mark on polls

Jawaharlal Nehru’s stamp on the first election is unmistakable. He not only personally led the election campaign on behalf of the Congress with great gusto, but seemed rejuvenated to leave the secretariat in Delhi for the open air of the maidans

Commenting on the smooth conduct of the first general election in India, the Manchester Guardian wrote on February 2, 1952: “The Working Committee of the Indian National Congress can draw pleasure from the extraordinary demonstration which India has given. If ever a country took a leap in the dark towards democracy it was India. Contemplating these facts, the Congress Working Committee may purr with satisfaction.”

From 25 October 1951 to 21 February 1952, the Indian people celebrated their first festival of democracy; dressed in their best, they lined up before 224,000 polling booths to elect 489 members for the Lok Sabha and 3,283 for the state assemblies. The vote was also treated as a valuable right and cast carefully, so that despite it being the first time for most people, only 3-4% of votes were invalid. When the election results were declared, it was found that nearly 46.6% of the eligible voters had cast their vote.

The first general election was conducted over a period of four months, and was a tremendous feat of organisation. Never before had such large numbers of people anywhere in the world been involved in an exercise of this kind. The election was held on the basis of universal adult franchise, with all those 21 years of age or older having the right to vote, with no qualifications based on gender, income, property, or education. This was a big change from pre-independence days, when even the last election held in 1945-6 was based on a very restricted franchise, with qualifications for eligibility to vote being determined by income, property, education, gender. Another big change was the absence of separate electorates which had determined constituencies not on the basis of territory, but on the that of religious belonging, thus dividing people into separate political boxes with no incentive to reach out across the boundaries.

Since the franchise had hitherto only been extended to roughly 13% of the people, most voters were first-time. In addition, the vast majority of the 173 million voters were from rural areas and three quarters were illiterate. More than a million officials had been pressed into service to register the voters via a house to house survey.

The spectacular achievement was in no small measure due to the strong democratic traditions established during the freedom struggle by the Indian National Congress and its leadership, especially Mahatma Gandhi, culminating in the Constituent Assembly and the adoption of the Constitution in 1950. It was no doubt also due to the strong commitment of the first prime minister to the democratic ideal and his constant pushing to speed up the process of organising the electoral exercise. His unhappiness at some unavoidable delays was well known. In fact, Jawaharlal Nehru’s stamp on the first election is unmistakable. He not only personally led the election campaign on behalf of the Congress party with great gusto, but seemed rejuvenated by the opportunity to leave the secretariat in Delhi for the open air of the maidans where he addressed innumerable mass meetings.

Travelling some 25000 miles by air, train, car and boat, he criss-crossed the country many times over, explaining to the multitudes who flocked to hear him the significance of the events they were participating in.

“As you know, there is no other example of general elections on such a vast scale as they are going to take place in India. It is a matter of courage to hold these elections, to make the necessary arrangements and let the people in their millions decide the fate of this country.”

He impressed upon them the necessity of a strong opposition in a democracy. “It is dangerous for the Congress or for any organisation to have it all its way. There must be opposition, there must be struggle, life is struggle, life is not ease.”“I do not want India to be a country in which millions of people say ‘yes’ to one man, I want a strong opposition.”

Nehru used the election campaign in which he addressed roughly 35 million people, or 10% of the total population, to educate the people about the challenges facing the country. Poverty remained the biggest issue, and could only be removed by promoting economic development, but that could only happen if the biggest obstacle, communalism, was removed. Divisive forces, of communalism, of provincialism, came in the way of progress. “If allowed free play,” he warned, communalism “would break up India”. And he declared: “Let us be clear about it without a shadow of doubt . . . we stand till death for a secular State.” In fact, Nehru turned the election campaign into a referendum on the nature of the Indian state. The people’s answer was to give a resounding defeat to the votaries of “Hindu rashtra” by confining them to 6% of the vote and 10 seats in the Lok Sabha.

Mridula Mukherjee is former professor of history at JNU and former director of Nehru Memorial Museum and Library

All Access.

One Subscription.

Get 360° coverage—from daily headlines

to 100 year archives.

HT App & Website