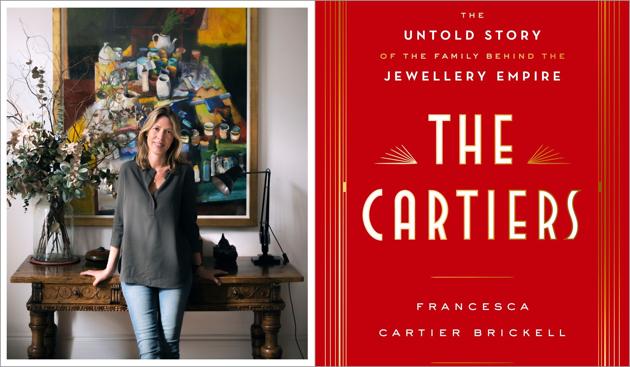

Letters from my Grandfather: Francesca Cartier Brickell on her earliest memory of a Cartier jewellery, the India link and how she keeps the family story alive

In an exclusive interview, Francesca Cartier Brickell talks about her grandfather, his letters, the Cartiers family story, her favourite vintage Cartier pieces and the link between the Cartiers and India.

There is something about old letters. They take you back in time and remind you of all the things you are made of. Letters have a different voice. They seal fate with ink in the most beautiful way and it is tough to decide whether we find these old letters or they find us. Some years ago in the South of France, when Francesca Cartier Brickell was visiting her grandfather, Jean-Jacques Cartier’s house celebrating his 90th birthday with four generations of the family gathered for the occasion, she came across a cluster of letters in an old leather trunk. The letters chose her. They were a proof of the fascinating journey of the Cartier family, their struggles, told and untold love stories, the complicated Cartier history and the many forgotten tales weaved in those words. Francesca could not bear putting back those letters in the trunk as she felt that the Cartier narrative needs to be told, a tale of personal memory and not just the brand story.

When Francesca came across the letters she had a sense – even then – that it was one of those moments she would never forget. She shares, “I remember that summer holiday I had been talking to my grandfather, Jean-Jacques Cartier, about the discovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb in Egypt in the 1920s, and how his father Jacques had been so excited that there was all that history suddenly available to learn from (it actually inspired him to create some truly stunning Cartier Egyptian Revival style jewels in the early 1920s). This felt like my Tutankhamen moment, opening a window into another era, into the real lives of my ancestors – and all in their own words. It was as exciting to me as discovering a chest of hidden jewels! After taking the case up to my grandfather, we spent the remainder of that summer reading those letters together, and suddenly those black and white ancestors that I had grown up seeing in photo frames around his house sprung to life. I realised then I couldn’t simply shut the trunk and leave them there for another few decades. This was a story that deserved to be told – if only to keep it alive for my children.”

In an exclusive interview, Francesca Cartier Brickell talks about her grandfather, his letters, the Cartiers family story, her earliest memory of a Cartier jewel, her favourite vintage Cartier pieces and the link between the Cartiers and India. Excerpts from the interview:

What are your fondest memories with your grandfather? How have those memories helped you shape the legacy into a book?

I was very close to my grandfather. He had run Cartier London until the 1970s when the business was sold (just before I was born) but he was so modest that you would never have known that he had created jewels for everyone from royalty to film stars. He was a very talented artist, always sketching something – and when we were little, he would draw us animals or fun cartoon sketches to make us laugh. I feel very lucky to have known him for so long – he lived into his nineties, and I was, fortunately, able to record his memoirs before he passed away. I learnt so much about him beyond the retired grandfather I had always known, and I came to understand where the family values that I had been brought up with had initially come from. He opened a window into the lives of our shared ancestors and I promised him I would try to keep the family story alive. In fact, that was the inspiration and motivation for this book.

Many people don’t know that the Cartier family was not privileged from the very beginning and it was quite difficult for the first two generations. What was the journey like?

My great-great-great-grandfather Louis-Francois Cartier, the founder of Cartier, was born into a working-class family. His mother was a washerwoman, his father a metal worker and though he wanted to stay in school his parents couldn’t afford it so instead he was sent out to earn his keep. He became an apprentice to a jeweller, Bernard Picard, and after working hard for many years he was able to take over Picard’s workshop, which he immediately renamed Cartier. It was small back then – leagues away from the glamorous showrooms his grandsons would later manage – but it was an important start. He did well and laid the foundations for future generations, including laying down the principles and family values by which the Cartiers did business.

His son, Alfred Cartier, married into some money, which definitely helped matters, but it wasn’t until the three brothers came on the scene at the turn of the 20th century that the business exploded onto the international scene. I think this was a function of the complementary talents and close bonds of the brothers. Of the three, it was Louis Joseph Cartier, the eldest, who was the most creative. For instance, he came up with the idea of the first wristwatch for men, and the idea of using platinum in jewels at a time when it was largely an industrial metal. Pierre Camille Cartier, the middle brother, was a brilliant salesman. He knew instinctively how to gauge the motivations of each individual client. For example, with Evalyn McLean (who bought the notoriously cursed Hope Diamond), he knew that by lending her the diamond overnight, he was more likely to secure a sale because she was more used to receiving beautiful objects than giving them back. And JacquesThéodule Cartier, the youngest brother and my great-grandfather was a mixture of his two brothers: He loved to design, but he was also a keen businessman and very good with people. In time, he secured an incredibly loyal client base, many of whom became friends. Of the three, Jacques was also the gemstone expert and his many trips to India, the world’s gemstone trading capital, would ensure Cartier stayed one step ahead of the competition when it came to precious stones.

What is your earliest memory of a Cartier jewel or piece?

I used to look a lot at old auction catalogues, Sotheby’s and Christie’s, with my grandfather where he would explain to me the inspirations behind a specific piece, and how it was made, the complications they encountered along the way etc. It was a great training – I learnt about an enormous range of pieces in that way – and I came to recognize that unique style, what made a piece truly Cartier, from Belle Epoque Cartier to the Cartier Tutti Frutti style to the bespoke watches made by Cartier London in the 1960s, like the Cartier Maxi-Oval, the Cartier Crash or the Cartier Pebble.

In terms of the first Cartier piece I owned, that was a Trinity Ring that I was given by my parents when I was a teenager. I loved it, so wearable and chic - even 100 years after it was first created -but sadly, I lost it swimming in the Mediterranean soon after. Fortunately, many years later, my husband (who had heard this sob story a fair few times) surprised me with another ring as a perfect birthday gift. Oh and I later found out that the ring I lost is in good company down on the Cote d’Azur seabed – a furious Coco Chanel threw jewels from her wealthy lover into the sea after finding out about his affairs.

What was the story behind Cartiers buying the Hope Diamond? Did your family believe in the curse?

The Hope was supposed to be cursed. Since its discovery in seventeenth-century India by Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, a French gem merchant, all those who had owned or been close to the 45-carat blue Hope Diamond stone were said to have suffered terrible fates. If you were to believe the stories, their endings included being torn apart by wild dogs in Constantinople, being shot onstage and, in the case of Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI (who had enjoyed the diamond as part of the French crown jewels) famously being beheaded during the French Revolution.

My grandfather told me how he had been worried that the notorious curse affecting the Hope diamond might affect his family because his uncle, Pierre Cartier, had at one time owned the Hope. His father wrote to him at boarding school, assuring him the curse was nonsense –my grandfather was enormously relieved!

When the Cartiers started a store in New York, they wanted to get on the radar in America. Instead of advertising in the press (which they believed back then wasn’t the best approach if they wanted to appeal to the elite), they decided to focus on word of mouth. And how better to get people speaking about Cartier than by buying a big, blue, notoriously cursed diamond - and particularly by selling it to such a well-known heiress as Evalyn McLean? She never believed the curse but still suffered a fair amount of bad luck over her lifetime. Her husband, Ned, ran off with another woman and later died in a mental institution, their family paper, The Washington Post, went bankrupt, her son was killed in a car accident, and her daughter died of a drug overdose. Vagaries of life, maybe, but enough to bolster the Hope’s notoriety.

What are your five favourite vintage Cartier pieces and why?

With the caveat that this list changes all the time as there are so many wonderful pieces, here’s a top-five list at the moment:

Tutti Frutti bracelets that join together to form a bandeau: they were bought by Lady Mountbatten before her husband became Viceroy of India and are now in the V&A Museum. I love the vibrancy of the jewels but also the practicality of the piece: the fact that it can be worn as bracelets or a bandeau depending on the occasion: 2 jewels for the price of one!

The Figurine Mystery Clocks of the 1920s: a mystery clock where the dial is made from transparent crystal and the inner workings are not visible. The caused a sensation when they were first made (the banker J.P. Morgan bought an early model) because no one could fathom how they worked. Even the salesman wasn’t told the secret so their sense of wonder could be passed to the client in its purest form: it was as if by magic. It took the Cartier workshop, led by the exceptionally talented clockmaker, Maurice Couët a full year to make the first one. And, by the 1920s, the mystery clocks that were being created were truly extraordinary. Perhaps the most extravagant example was the jade elephant mystery clock bought by the Maharaja of Nawanagar in 1928.

An emerald pendant brooch made with carved Indian emeralds: This was bought by American heiress Marjorie Merriweather Post and currently in her former residence, Hillwood Museum in Washington, where I gave a launch book lecture in November 2019. She was a great collector and would be a client of Cartier for many decades, but this is one of my favourite of all the pieces she bought, so striking and yet timeless.

The Trinity ring: I mentioned this above, now this is a simple piece – no big gems but so wearable, even 100 years after it was first created by Louis Cartier for, it is said, the French writer and artist Jean Cocteau.

The Tank Watch: Not a jewel but I have to include it as it is so classic and timeless and works as well with jeans as a dress. I wear mine all the time.

Tell us about the links between the Cartiers and India.

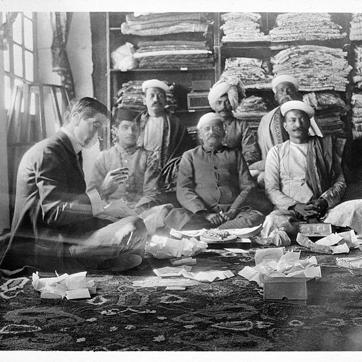

My great-grandfather Jacques’ first visit to India was in 1911 at the time of the Delhi Durbar but he visited regularly through the 1920s and 30s, along with trusted employees like Maurice Richard and Clifford North. Though the trips took him away from home and family for months at a time, Jacques loved his visits to India – he was fascinated by its history and culture even tried to learn Hindi with the help of a language book and the ship’s crew on journey over there! He was awed by the country – everything from the architecture to the fabrics, to the colours had an enormous effect on him. “Out there everything is flooded with the wonderful Indian sunlight,” he wrote, “one does not see as in the English light, he is only conscious that here is a blaze of red, and there of green or yellow”. He compared it to an impressionist painting. “Nothing is clearly defined, and there is but one vivid impression of undreamed gorgeousness and wealth”.

Over time, India became increasingly important for the Cartiers. I would say this was for three main reasons. Firstly: the clients. The list of Indian royal families who entrusted the Cartiers with their custom was extensive and included those from Indore, Kapurthala, Nawanagar, Calcutta, Jodhpur, Jaipur, Patiala, Hyderabad, Baroda and Bahawalpur among others. Secondly: the gems. India was the gem-capital of the world and as Jacques scored the gem markets out there for precious stones to bring back home, so Cartier gained a reputation as having the highest quality rubies, sapphires and emeralds in the West. Thirdly: the inspiration. This may have been a by-product of Jacques’ trips rather than an early motivation for his travels East but it was no less important. The Indian colours inspired vibrant coloured jewels (he called them ‘Hindou jewels’ but they would later become known as ‘Tutti Frutti’), while Indian carvings and motifs fed into designs on everything from tiaras to cigarette cases.

Your book captures never-heard-before stories, betrayals, love stories as well as the wider social context. How did you weave all that into the narrative?

Before writing, I spent a lot of time structuring the narrative. I had to keep crisscrossing from Paris to London to New York, which required hours working on chapter outlines on big whiteboards trying to keep the overall thread as organised and clear as possible. In total my book covers four generations, that’s plenty of characters acting in multiple countries through over a century of ground-breaking world events. Yes, of course, there’s a lot of information and history, but there is also a lot of action and drama! After all, they lived through exciting times – everything from the marriage of Napoleon III to Empress Eugenie, to the Siege of Paris, the Russian Revolution, two world wars, boom time in America, India of the Raj, the Great Depression, the rise of Middle Eastern petro-dollars, all the way to the Swinging sixties. So I needed to convey all that but most of all, I wanted the characters to come to life for the reader as they had come to life for me when I read the letters and listened to my grandfather talk about them. As I wrote, I asked myself how would I explain this event or that character in an engaging way if I was just having a chat with a friend?

Finally, what are the key elements you wanted to incorporate into ‘The Cartiers’ in terms of its design?

It’s mostly a book about the family and the people behind the jewels, not a coffee table book that is filled with jewellery images. I did a lot of background research but I didn’t want the book to become weighed down by detail so I put the sources into endnotes so they wouldn’t disrupt the reader but remained accessible. When I was reading history books, I found it so helpful when authors shared their sources like this.

I also wrote a series of jewellery spotlights, where I describe in detail a few special pieces in separate “spotlights” (like the Romanov Emeralds or the Crash Watch). I tried to offer a variety of different creations, from jewels to watches to cases but I also wanted to discuss pieces where there was a story to tell behind their creation.

Image-wise, I included a lot of photographs of the family to bring them to life as people in normal settings (such as Jacques and Nelly and their children having fun on the slopes on a skiing holiday) and not just in a posed formal way. But I did also include colour inserts of Cartier jewels as I felt it was important to the story to see how they changed through the eras. So, as you flick through the colour inserts, you have a journey through time, each page representing a different era to show how the Cartiers were continually innovating while always focusing on the highest quality in terms of the design, gems and craftsmanship. I wanted to show the reader – just as my grandfather had shown me – how, although the jewels made in 1900 were very different to those made in the 1930s or the 1960s, all of them are recognisably Cartier.

Finally, when you open the cover of the hardback book, you are confronted with a montage of some of the old letters and telegrams and sketches I found in the trunk. I love the way this has turned out. I wanted the reader to have that sense (a bit like I had when opening the trunk) of seeing all that history just lying in front of them. You can read about the family in the book and it might almost read like a novel at times but it’s true, and hopefully, the endpaper bring this home to see those real-life letters written over 100 years ago.

Catch your daily dose of Fashion, Taylor Swift, Health, Festivals, Travel, Relationship, Recipe and all the other Latest Lifestyle News on Hindustan Times Website and APPs.

Catch your daily dose of Fashion, Taylor Swift, Health, Festivals, Travel, Relationship, Recipe and all the other Latest Lifestyle News on Hindustan Times Website and APPs.