Cause and Effect: Importance of the humble straw in the fight against pollution

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development estimates that around 380 MT of plastic waste is produced globally each year.

The United Nations Environment Programme has announced that the second part of the fifth session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) to develop an international and legally binding instrument on plastic pollution will take place in August in Geneva.

The treaty, however, hangs in balance like most international agreements since the return of Donald Trump to the White House.

On February 10, US President Donald Trump issued executive orders aimed at encouraging purchase of plastic drinking straws, pushing back efforts by his predecessor to phase out single-use plastics and tackle waste.

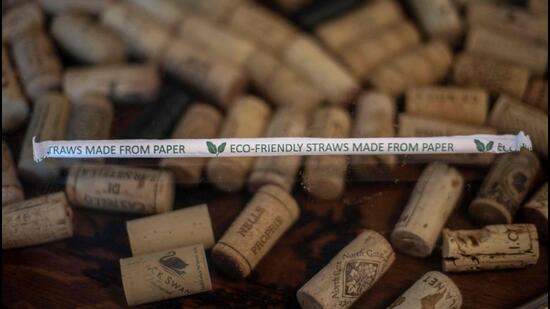

“We’re going back to plastic straws,” Trump said as he signed the order, saying that paper straws “don’t work”. “I don’t think plastic is going to affect a shark very much, as they’re munching their way through the ocean,” Trump said. While he may be right in the first part of his statement, the second is in fact incorrect with ample proof of ocean life being affected by plastics.

Trump’s order seeks to reverse President Joe Biden’s work who had proposed environmental measures to lower consumption of non-biodegradable single-use plastics. He also rescinded a policy to end the use of all single-use plastic products on federal lands by 2032. Locally, a number of US cities and states — including Seattle, Washington; California; Oregon; and New Jersey — have adopted rules that limit the use of plastic straws or require that businesses provide them only after being asked by customers.

Previous estimates on plastic straw use in the US have put the number at 500 million a day, but this number, arrived at by then a nine-year-old Milo Cress in February 2011, is highly disputed.

The numbers that aren’t disputed are on plastic consumption, plastic waste and plastic emissions.

The Global Plastics Outlook from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development estimates that around 380 million tonnes of plastic waste is produced globally each year, with around 23 million tonnes of that finding its way into the environment. It estimates about 1.7 million tonnes of that ends up in the ocean annually, although other studies have put the figure at somewhere between 4.8 and 12.7 million tonnes.

If no new controls are introduced, the amount of plastic waste dumped into the environment is projected to rise from 81 million metric tons in 2020 to 119 million tons in 2040, according to the research published last year.

Of 380 million tonnes of plastic waste produced, about 43 million tonnes comes from consumer products that include single use plastics from the food and beverage industry. Roughly 14 million tonnes of this, or 3.7% of total plastic waste, is made of polyproplyene, the main material used in plastic straws.

When looked at more closely, the data suggests that plastic straws account for a minuscule amount of the total plastic generated and used. Separately, alternatives may not be as environmentally damaging as previously believed. Paper straws assessed by researchers at the University of Antwerp, Belgium, were found to contain more forever chemicals – per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances or PFAS – than plastic. These long-lasting PFAS can stay in the environment for decades, can contaminate water supplies, and are associated with a range of health problems.

The researchers behind the study say their results suggest that paper straws – along with their bamboo counterparts, which were also found to contain PFAS – are not necessarily a more sustainable alternative to plastic. The higher levels of forever chemicals they contain, they say, could be seen as a question mark over how “biodegradable” these alternatives are. To add to mistrust of paper straws, they disintegrate so much upon use that they are often rendered non-recyclable, or have a plastic coating on the inside, or are too thick for recycling.

Additionally, most recyclers refuse products contaminated with food or beverage.

An impact assessment study by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) of the government of the United Kingdom in 2018 found that when sent to landfills, “plastic emits very few carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2 e) emissions relative to paper”.

So why the campaign against plastic straws?

Perhaps, plastic straws became the poster child in the campaign against plastic because of the role an individual can play in limiting its use. Depending on which part of the environment a person is looking at for the impact of straws, it perhaps would be better to reuse each kind of straw or maybe shun them altogether.

In the meantime, consumers and producers will look to the August meeting on plastics in the hope of some legally binding treaty, which as the history of climate negotiations goes, has been elusive.

All Access.

One Subscription.

Get 360° coverage—from daily headlines

to 100 year archives.

HT App & Website