Greed, thrill of beating system incentives for match-fixing

The protagonists involved, the ingenious ways in which corruption can intrude into the sport almost unobtrusively, makes for riveting viewing. But by the end of it one is left with a sinking feeling that cricket may still be far removed from being a clean sport.

I’ve watched Al Jazeera’s documentary ‘Cricket’s Match-Fixers’ a few times since it was first telecast on Sunday and it’s had me both fascinated and depressed. (Here’s the link for those who haven’t seen it: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uYlk4izYVmw)

The protagonists involved, the ingenious ways in which corruption can intrude into the sport almost unobtrusively, makes for riveting viewing. But by the end of it one is left with a sinking feeling that cricket may still be far removed from being a clean sport.

READ | Three Test matches featuring Indian cricket team were fixed, claims Al Jazeera sting

The sting operation is done by an undercover journalist over 18 months and features some former international cricketers (among them Pakistan’s Hasan Raza), former first-class players (including Robin Morris from India), a Sri Lankan pitch curator, a tournament promoter and a frontman for an alleged underworld betting syndicate.

It is difficult to gauge whether those caught on camera are not speaking with affected bravado to make a fast buck out of a punter beguiled by the easy money to be made.

The fixers claim that curators can be asked to ‘doctor’ a pitch as they dictate, they can get a short-format league started in which players can be bought to spot fix and influence match results. Why, even get ‘sessions’ customised, as it were, in a Test match!

READ | Al Jazeera TV sting sends cricket world in a spin as ICC demands all evidence

What boggles the mind is not just the nonchalance with which such insidious methods are discussed but scenarios being played out as forecast by the alleged fixers in two Tests in India in 2016-17, one each against England (Chennai) and Australia (Ranchi).

The documentary highlights three English and two Australian batsmen (names blanked out in both cases) who the bookie says would play in a certain manner in a period of play. It transpires as he promises. Was this co-incidental or is there something deeper?

READ | Michael Atherton ‘highly sceptical’ of England, Australia spot-fixing claims

Given the texture and tenor of cricket, it is impossible to separate the real from the fake. No balls, wides, dropped catches, batsmen ‘downing shutters’ nearing close of a session, losing rhythm and timing or regaining it are intrinsic to the game. Or can be contrived. And therein is the problem.

Former England captain Michael Atherton, while acknowledging the dangers from fixing in his column in The Times (London), has expressed scepticism on the Al Jazeera story. “But highly paid international players in very visible, high profile matches?” he questions.

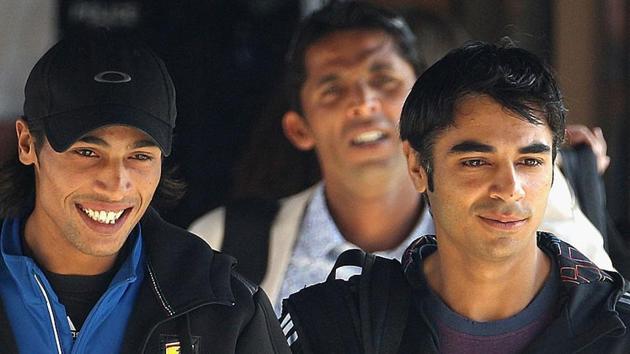

Atherton’s being either naïve or hopeful. Match-fixing scams in circa 2000 (featuring Hansie Cronje, Salim Malik and Mohammed Azharuddin among many) and 2010 (when Salman Butt, Mohammad Asif and Mohammad Amir were exposed by a newspaper sting) involved international players, highly rewarded and revered.

READ | Cricket corruption ‘goes right to the top’ in Sri Lanka, says former captain Arjuna Ranatunga

Even in the IPL corruption scam of 2013, though the players involved were not so high profile, they were hardly beggarly, rather from the top 5 % income earners in the country.

Why players would cheat with everything going for them is a vexing socio-psycho-ethical question. The thrill of ‘beating the system’ can be an incentive, but more certainly it is greed. There is enough evidence of human nature that greed can be without limit.

Mentoring players from an early age is an important endeavor to prevent corruption. Alas this is no guarantee that an individual will not succumb to greed. Which is why stringent checks, balances and other measures are imperative.

In the Indian context, legalising betting has long been advocated, including by Justices Mukul Mudgal and RM Lodha, both of whom investigated into the 2013 IPL scam. A bill to make corruption in sport a criminal offence, (like New Zealand passed in 2014 with a seven-year prison term for the guilty), was also mooted in India. Both these provisions for some reason hang fire. (Wake up government of India!)

Coming back to the Al Jazeera sting, without forensic tests confirming what the ‘sting’ shows or other compelling evidence, no conclusive proof that could stand scrutiny in court emerges.

However, experts who feature in the documentary, including a former investigator with Interpol, aver that the evidence is incriminating.

The ICC, after getting bellicose about the documentary being telecast without prior approval (how supercilious!) has agreed to investigate.

The cricket boards of England, Australia, India and Sri Lankan have extended full support. This is the sensible way forward rather than being ostrich-like, unconcerned about the threatening clouds that may be circling this great game.

The author is a senior cricket writer. Views expressed here are personal.