When India and China talked

The history of peace is much longer than the history of discord. There are common challenges

While its implementation on the ground will be a key test, external affairs minister S Jaishankar and Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi deserve felicitations for agreeing on September 11 that our troops “should continue their dialogue, quickly disengage, maintain proper distance and ease tensions”. Meeting in Moscow in the midst of tension, and with our experience in Ladakh being agonisingly fresh, their agreement is an accomplishment of not just bilateral diplomatic reflexes but of practical intelligence.

It is, in fact, the most tangible, ground-level Sino-Indian development since the signing of the India-China agreement in Qingdao on June 9, 2018, on the sharing of hydrological data on the Yarlung-Tsangpo or Brahmaputra. Given our boundary dispute, China’s position on Aksai Chin, Arunachal Pradesh and post-Doklam, that agreement reached by Prime Minister (PM) Narendra Modi with President Xi Jinping was historic. I thought then and believe now even more, that it was, in fact, civilisational. In the Qingdao Agreement, India succeeded in persuading the upper-riparian “parent” to view the river downstream non-hegemonically. This was a gain for gravitational and ecological intelligence for both nations, faced with what Ma Jun, director of the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs in Beijing, in a 2017 interview, described as “the harsh reality that …it is not easy to find clean rivers and lakes anymore” and “the quality of groundwater aquifers is still deteriorating”.

A water crisis looms over our two nations, dependent as both are on rain-fed rivers, with global warming reducing sources for snow-fed rivers. Civilisations have, in history, been about river-based and river-nourished habitation.

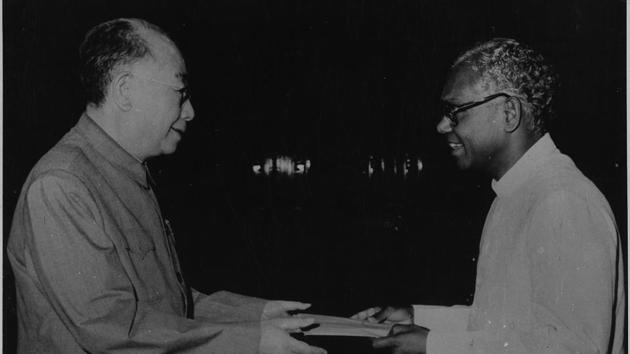

Seeing the reports from Moscow, I recalled the presentation of credentials in June 1998 by the new Chinese ambassador to New Delhi to then President KR Narayanan. Both the ambassador and the president knew that the occasion was not just ceremonial. Nothing between China and India can be “just ceremonial”. President Narayanan had, early in his career as an officer in the ministry of external affairs, been on the China desk. And being the scholar that he was, he used the opportunity to study Sino-Indian relations in-depth and prepared a paper on the subject.It dealt with both the strategic and civilisational dimensions of our ties. Shortly before the ceremony, he asked for a copy of that closely-typed paper from the ministry and re-read it. Those like me privileged to be serving on his staff knew he took no event for granted, and studied not just official briefs but old and new books as well. He used that learning, without ostentation, in the conversations that ensued around the occasion. The Chinese ambassador-designate knew, too, that the president he was presenting his credentials to, was not “just someone who happened to be president”. After the 1962 war, the two neighbours had withdrawn their ambassadors. When the positions were resumed, in 1976, Narayanan was chosen as the ambassador of India to the People’s Republic of China.

So it was as one who knew China that President Narayanan received the new Chinese ambassador to New Delhi. He had worked on the draft welcoming speech given to him, enriching it with his own special touches, like in these words: “As a sister civilisation in the East, India has had extensive contacts and exchanges with China which have been not only mutually rewarding but enriching for the Asian and world civilisation”. And in a way typical of the philosopher-President, he added: “We must promote exchanges at the level of the peoples of India and China”.

Two years later, as President Narayanan was leaving on a State visit to China, the then Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee told him that he hoped the visit “will open a new chapter in our relations”. I cannot say if it did that but the visit, in which he was accompanied by a political rainbow comprising Members of Parliament (MPs) Sushma Swaraj, Somnath Chatterjee, Sushil Shinde, S Ramachandran Pillai and a non-MP, Mohammed Afzal Meem, certainly made an impression there. “You were born in 1920”, President Jiang Zemin told him, “I was born in 1926. We belong to the same generation…We must make efforts that would be beneficial to both our peoples.” When President Narayanan called on the then Premier Zhu Rongji, he pointed to the wide spectrum of Indian politics represented in the Indian delegation and said all parties in India were united in wanting improved relations with China. And Zhu, thoughtfully, said something I can never forget. “There is a touch”, Zhu said, “of Indian civilisation in Chinese culture.”

President Narayanan, on more than one occasion during that visit, stressed on the fact that the time during which discord has marked our ties is much shorter than the time in which we have had concord. There is no telling how our relations will fare. But it is important that we do not let go of our sense of the two nations’ past in peace and give the maximum possible scope to what the Jaishankar-Wang text has described as “continuing dialogue”.

And going beyond the immediate concerns of that dialogue, we must strive to keep the Qingdao Agreement on track for it is about the waters of life.