The Republic of India is not the home for all its founders imagined

In this last week of 2013 that has seen sleaze in politics and misdemeanour of all kinds, we ought to know who and what ‘we’ are as a people. Gopalkrishna Gandhi writes.

Time is timeless, calendars mere memory joggers and watches no more than silent or noisy alarm bells.

And barring a few ‘un-contacted’ people like the perilously few on the North Sentinel Island in the Andaman Islands, time-free ‘original people’ are not to be found any longer on the planet. But if such people did exist, they would doubtless be happier than us, their time-bound fellow humans. They would conceivably be far more creatively occupied, for want of the manacles of measured time, than us.

They would, of course, not understand the end of the year business. The beginning of a new year would mean nothing to them, the beginning of a new day, with its signals of the ambient weather, its likely mood-swings, the growlings of the sea and the roarings of the sky, meaning more, much more, than they do to us in our sealed-up cement jungles.

Not all that long ago some Indian anthropologists, including TN Pandit, found themselves trapped among the reefs off the North Sentinel Island. Sentinelese ‘warriors’ were out in a trice, gesticulating belligerently at the team.

Vocalised attempts at expressing goodwill met with contempt and, fortunately, with no projectiles adding point to the emotion. Then something — strange to the anthropologists — happened.

The men and women paired off, a few ‘warriors’ being left to guard the island.

These pairs, according to the anthropologists, then "sat on the sand in a passionate embrace…this… being repeated by other women, each claiming a warrior for herself, a sort of community mating, as it were".

Keeping the description on the correct side of any voyeuristic impropriety, the eyewitness account says, "Thus…when the tempo of this frenzied dance of desire abated, the couples retired into the shade of the jungle".

Some say the Sentinelese number no more than about 50, while others viewing them from afar through census lenses say they should be around 500. Be that as it may, the Sentinelese are Indians without knowing what India is, and are ‘governed’ by the Union Territory of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands without the foggiest idea of what that means or can mean.

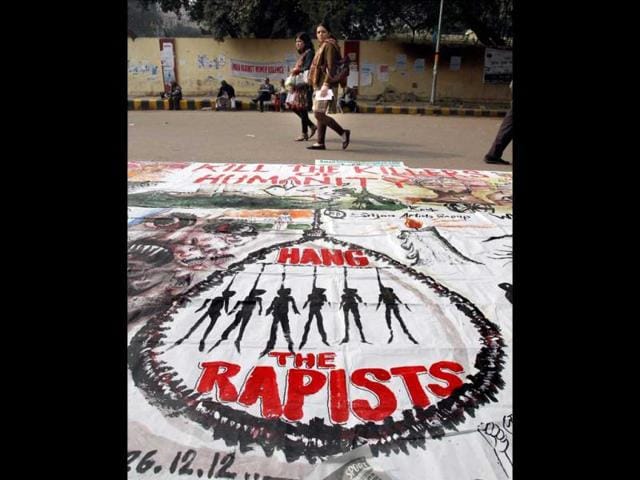

There being no hotel lifts and suites in the North Sentinel Island, nothing like what is said to have been attempted by an editor in Goa or a former judge in New Delhi can ever happen among these people. No woman would be attacked there by debased males as the Delhi gang-rape victim was.

No Pandher-type child abuser and murderer can possibly be found among them.

For that matter no man would be hacked and burned to death as Ehsan Jafri was in Ahmedabad on March 1, 2002, with 69 others at the same spot, the same day, and for the same reason, namely, that they belonged to a religion other than the religion of the murderers. They, presumably, have no religions of the kind we know, and therefore none of our religious bigotry.

So, am I romanticising the tribal way?

I am not. I just want to say, in this last week of our current year, which has seen sleaze in cricket, in politics, in government, attempted rape, ‘actual’ rape, rape with murder, lies, perjury, misdemeanour by very important and influential people, un-edifying conduct by a diplomat leading to unacceptable retaliation by her host government, that we ought to know ourselves. We ought to know who and what we are as a people, notwithstanding risks of generalisation.

‘We the people of India’ are a creation of optimistic imagining, nation-building animation and political self-deluding. In reality, we are only the ‘we’ of present company. When we use that self-flattering pronoun, we are talking of a very small number that are ‘we’.

Not only are we incapable of ever thinking of the Sentinelese when we ‘we’ ourselves, we invariably we in one kind to we out another. Far from making it an inclusively republican dynamo of the plural of ‘I’, we have made ‘we’ a most walling-in and walling-out concept.

Speaking in Bangalore recently, distinguished sociologist Andre Beteille spoke of the Indian propensity for creating factions. The anthropologist, who first drew attention to factions in Indian politics, he said, was Oscar Lewis, while Paul Brass later wrote a book on factional politics within the Congress in Uttar Pradesh.

Everywhere there are categories, groups, identities. But the phenomenon of coteries, cliques and factions thrives in India as in few other places. All political parties, public organisations, even, alas, many NGOs, faculties, corporates, sports ventures, cultural associations, have factions.

Through the process of a very typical Indian reductionism, ‘we’ are cosiest when down to its smallest possible final un-factionable we.

Caste’s grip has, without doubt, loosened. And the middle class’ bulge has made that the dominant class in India, taking away the sharp edge of the earlier polarisations of the Marxist sense of class.

But the reign of factions, cliques and coteries has tightened beyond belief. Indian democracy is not so much about political parties as about political factions.

We dream of the pot, but live in its shards. Intrigue rather than direct contestation, whispers rather than straight speech, have given us walls with ears and corners with tongues.

The pairing of woman and ‘warrior’ among the Sentinelese that the anthropologists described is the aboriginal and most foundationally creative ‘faction’ in human life. But that integer of Sentinelese life is not what makes and sustains life among ‘we the people of India’. Crass self-interest does.

The Republic of India is not the home for all its founders imagined but a honeycomb of hexagonal cells that protect their own larvae and their stores of honey and pollen.

If there is an exception, apart from North Sentinel Island, it lies in two arenas where life is whole not factious, subtle not gross — the pre-school square and the ICU. The purity of life’s dawn in the first and the torpor of dusk in the second give us a choice — self-renewing hope or self-mortifying resignation.

(Gopalkrishna Gandhi is a former administrator, diplomat and governor)

The views expressed by the author are personal