Silver lining of 2014 elections: the professional as politician

The freedom movement was largely led by those who exchanged professional success for an uncertain life of struggle. With independence came the career politician, in quest of prestige and profit, Ramachandra Guha writes in a new HT column.

The Indian freedom movement was largely led by those who exchanged professional success for an uncertain life of struggle and sacrifice. Mohandas Gandhi, Motilal Nehru and Vallabhbhai Patel each abandoned a lucrative legal practice. Subhas Chandra Bose and Morarji Desai turned their back on careers in the civil service. Jamnalal Bajaj built a flourishing business empire before joining Gandhi in prison. Had they not chosen politics as a vocation, Maulana Azad and Ram Manohar Lohia could have been famous academics; Jawaharlal Nehru and Jayaprakash Narayan prosperous writers.

Some outstanding women also subordinated professional ambition to the wider movement for national emancipation. Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya left behind a promising career in the theatre to go to prison. Sushila Nayar and Soundaram Ramachandran were medical doctors who bent their training to social service rather than augmenting their bank balance.

This trend was present outside the Congress as well. BR Ambedkar sidelined his legal career to focus on the emancipation of the Dalits. Syama Prasad Mookerjee was a successful university administrator before joining politics full-time. Several Communist leaders could have had alternative careers in journalism or academics.

In an unpublished novel written in the early 1950s, Verrier Elwin noted how khadi, once 'the symbol of insurgence against British rule', had now become 'an almost official uniform, the sign of authority and power'. With independence came the career politician, he (much less often she) who never had, and often never could conceive of, a career outside the party office, the legislature, or the secretariat. The odd lawyer-turned-MP apart, the political class was now overwhelmingly composed of individuals in quest not so much of public service as prestige and profit.

Over the years, the political class has become increasingly self-reproducing; as the proliferation of 'hereditary' MPs shows. For some people, politics is family business; for others, just business, a means to acquire wealth through the preferential allocation of contracts once in office. Studies by the Association of Democratic Reforms demonstrate how, between elections, the wealth of MPs and ministers rises in ever increasing proportions. The buying and selling of Lok Sabha tickets and Rajya Sabha seats, and the increasing entry of real-estate dons and mining mafiosi into state and national legislatures, are further manifestations of the corruption of the political class as a whole.

The larger context is depressing; even so, the candidates' lists for the 2014 elections indicate a modest revival of the idea of the professional-turned-politician. Consider the case of Sugata Bose, who has taken a leave of absence from his chair at Harvard University to contest as the Trinamool candidate from Jadavpur South. Or of Rajmohan Gandhi, acclaimed biographer of Patel and Rajagopalachari, who is now AAP's candidate for the East Delhi constituency. Another AAP candidate with a sterling record of public service is Medha Patkar, who has spent three decades fighting for the rights of peasants, tribals, and slum-dwellers rendered homeless in the name of 'development' and 'progress'.

The two national parties have their own exemplary professionals in the fray. Nandan Nilekani was an outstanding CEO of the iconic software company Infosys, before entering government to start the Unique Identity programme.

He is now the Congress candidate for Bangalore South. Meanwhile, the BJP has nominated, as their candidate for Jaipur Rural, a man who has had two extremely demanding careers already. This is Rajyavardhan Singh Rathore, who served almost two decades in the Indian Army, while winning an array of Asian, Commonwealth, Olympic, and World Championship medals in shooting on the side.

I don't suppose all these candidates will win. But I hope at least some do. They would bring a much-needed seriousness and depth to Parliamentary debate. Further, their status as MPs would allow them, individually and collectively, to constructively shape public opinion as a whole.

Were Nilekani to win, he would bring to Parliament the experience of a successful (and technologically adept) entrepreneur; Rathore, that of a long-serving army officer-cum-sportsman. As an activist who has lived her life with the disprivileged, Patkar can make discussions of social welfare more grounded. Bose's insights into education policy would draw upon his years spent teaching in the finest universities in the world. As for Rajmohan, he is a scholar-journalist with an unparalleled knowledge of modern Indian political history, who knows better than anyone alive what Ambedkar, Nehru, Patel and company intended Parliament to be.

There is a final reason for us to hope that this new generation of public-spirited professionals succeeds in politics. Indian parties have become increasingly subject to the wishes of a single individual (or family). The cult of the Gandhis in the Congress has now been equalled, if not surpassed, by the cult of Arvind Kejriwal in AAP and of Narendra Modi in the BJP. Regional parties exhibit this tendency in an even more exaggerated form. In this context, those who have independently made their name outside politics are far less likely to unconditionally accept the word of the Leader. Where their party-mates might use flattery and intrigue to promote themselves, they will instead use reason and experience to promote good ideas in their parties, in Parliament — and beyond.

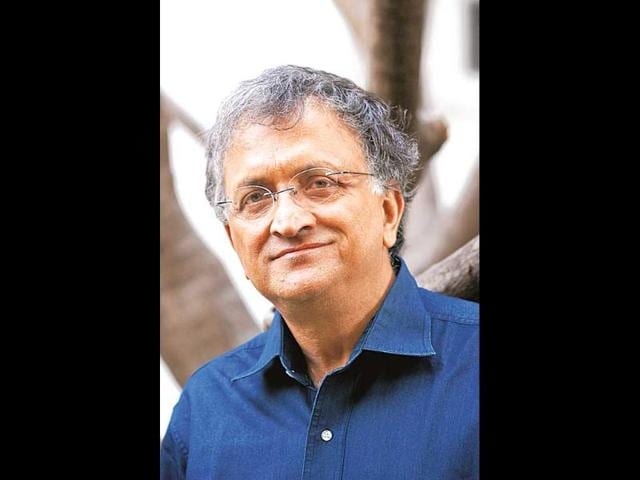

Ramachandra Guha's most recent book is Gandhi Before India You can follow him at @Ram_GuhaThe views expressed by the author are personal