Remembering Kamal Joshi: A hillman and a true national hero

Local heroes such as Kamal Joshi, who silently, self-effacingly, serve society, with no interest in fame or power or money, do not get the attention of the media. To be sure, they do not want it either. Yet it is these ‘local’ heroes who more truly embody the spirit of democracy and freedom in our Republic.

Back in 1983, when Arvind Kejriwal was a little schoolboy in short pants, a friend and I founded an organisation called AAP. This stood for the Association of Asthma Patients. My co-founder was a Garhwali scientist named Kamal Joshi, and we discovered our common ailment while huffing and puffing on a hill outside the town of Pithoragarh. Kamal and I had both come here on the invitation of the historian Shekhar Pathak, who had just brought out the first edition of an annual on Himalayan affairs called PAHAR (meaning ‘mountains’ of course, but also standing for Peoples Association for Himalaya Area Research). After the journal was formally released, we were taken on a tour of the countryside, where magnesite mines had left deep scars. While the lanky and impossibly athletic editor of PAHAR bounded up the mountain side, his two asthmatic friends lagged lamentably behind.

Back in 1983, when Arvind Kejriwal was a little schoolboy in short pants, a friend and I founded an organisation called AAP. This stood for the Association of Asthma Patients. My co-founder was a Garhwali scientist named Kamal Joshi, and we discovered our common ailment while huffing and puffing on a hill outside the town of Pithoragarh. Kamal and I had both come here on the invitation of the historian Shekhar Pathak, who had just brought out the first edition of an annual journal on Himalayan affairs called PAHAR (meaning ‘mountains’ of course, but also standing for Peoples Association for Himalaya Area Research). After the journal was formally released, we were taken on a tour of the countryside, where magnesite mines had left deep scars. While the lanky and impossibly athletic editor of PAHAR bounded up the mountain side, his two asthmatic friends lagged lamentably behind.

Kamal and I were brought together, in the first instance, by our love of the Uttarakhand Himalaya; and in the second instance, by our affection for Shekhar, the historian, trekker, campaigner, writer, editor, and speaker who is the very embodiment of the Uttarakhand that both Kamal and I knew and loved. But that we were both chronic asthmatics provided a third, and intimately personal, connection. Some people bond over varieties of pipe tobacco; others over varieties of single malt whisky. Kamal and I bonded over bronchodilating drugs, composed of the chemicals Ephedrine and Deriphyline, and prophylactic inhalers with names like Seroflo and Formonide. Among the delights of our founding AAP was that the bronzed, supremely fit, fabulously healthy Shekhar was excluded from its membership.

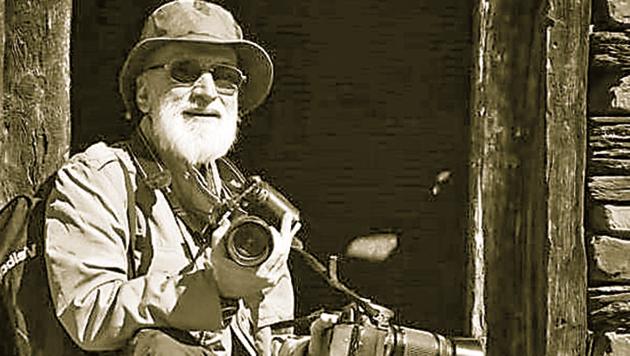

Kamal was born and raised in the town of Kotdwar, which is located on the edge of the Himalaya, where the hills meet the burning plains. He was an outstanding student of chemistry, and could have made a research career had not the fumes in the laboratory set off his wheezing. With a high first class in his Masters degree, he could have gone into covenanted government service; but neither routine nor pomposity much appealed to him, so he declined to become a babu too. In the event, he became a freelance writer and photographer, travelling through his beloved hills, chronicling landscapes and lives. Despite his physical handicap, he willed himself to make arduous treks across the high mountains, a pouch of pills and inhalers in his rucksack giving him the courage and the sustenance to do so.

Since that first issue of PAHAR was launched in 1983, some 17 further volumes have been produced; each several hundred pages long, composed of original essays on Himalayan culture, ecology, history, society, literature and politics. All along, Kamal curated the visual parts of the journal; and also helped with editing, fund-raising, and the like.

I met Kamal often in the 1980s; and erratically in the 1990s. He had an extraordinary effervescence of character despite his infirmities and illnesses. Thereafter, with me based in Bangalore and he in Kotdwar, we lost touch. I was saddened to hear of his death in 2017. Those who knew him better and longer than I were, of course, even more distressed by his passing. Fortunately, they chose to sublimate their grief in an admirably constructive manner, by holding an annual event in Kamal’s memory.

I missed the first such event, but was fortunate enough to attend the second, organised earlier this month in the capital of Uttarakhand, Dehradun. It was an all-day affair, held in the Town Hall, featuring talks, conversations, and a play. Despite it being a weekday, the hall was full. The audience was very diverse; composed of teachers, students, civil servants, traders, doctors, et al. The speakers included three quite remarkable Uttarakhandis. One was the aforementioned Shekhar Pathak; a second was Professor Pushpesh Pant, known to some as a scholar of international relations, to others as an expert on the culinary history of India, but here appearing as his original, authentic self, a hillman with a passionate interest in his state and his people. The third was Kamal’s own younger brother, Dr Anil Joshi, who has done pioneering work in water conservation and environmental sustainability in the hills. However, some non-Uttarakhandis spoke as well — such as the acclaimed cinematographer Apurba Kumar Bir, who had come from Mumbai to judge a competition for young photographers in Kamal‘s memory.

When he was alive, I hesitated to think of Kamal as an “activist”, for that term conveys a grim, humourless person with a tendency to think in black-and-white. This was foreign to my friend’s character. And yet, for all his sense of fun and mischief, Kamal was an activist, deeply engaged with his society, seeking to rid it of suffering and injustice. He was (as it were) active in many social movements, including those against large dams, against alcoholism, and, above all, for the creation of a new state of Uttarakhand. When the state was formed, in 2000, he — like many others — was deeply dissatisfied with its choice of capital. Dehradun, a town located at one corner of Uttarakhand, was not appropriate for a mountain state, and Kamal was of the view that the capital should be shifted to the inner hills, where a suitable location had been found near the village of Gairsain.

The media today is obsessed with national heroes — with larger-than-life prime ministers, captains of cricket teams, and the like. The language Press has more time for state-level heroes — but these tend to be film stars. Those, like Kamal, who silently, self-effacingly, serve society, with no interest in fame or power or money, do not get the attention of the media. To be sure, they do not want it either. Yet it is these “local” heroes who more truly embody the spirit of democracy and freedom in our Republic. The people who had gathered in the Dehradun Town Hall that day to honour the memory of Kamal Joshi understood this very well.