Jayaprakash Narayan’s fears are as valid now as they were in 1966

JP had started life as a Congressman. Even after he left the party, he retained a close personal friendship with Jawaharlal Nehru. Nehru’s daughter Indira Gandhi was prime minister in 1966, yet JP did not hesitate to remind his audience of how the Congress had contributed to the decline of public morality in independent India

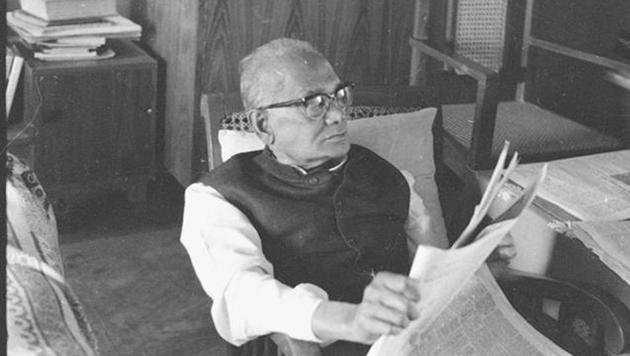

Among the more fascinating figures in modern Indian history is Jayaprakash Narayan. Radical socialist and hero of the Quit India movement while the British ruled us, he had three distinct careers after Independence: as a labour leader and Socialist Party activist; as a Sarvodaya worker and striver for peace in Kashmir, Nagaland, and the Chambal Valley; and finally as the leader of a nation-wide movement against the authoritarian regime of Indira Gandhi.

Read: Why we must listen to Jayaprakash Narayan on Kashmir

It was while he was a social worker that Jayaprakash Narayan was asked to be the Chief Guest at the annual convocation of my alma mater, the University of Delhi. The function was held on 23rd December 1966, almost exactly 50 years ago.

JP began his Convocation Address by speaking of the less than satisfactory state of higher education in the country. He noted that ‘the examination system seldom discounts neglect of studies’ (namely, that one could be irregular in classes, yet commit notes and guides to memory and get high marks). University teachers for their part, remarked JP, ‘seldom lead, inspire or interest the student to the gathering of knowledge’.

JP then spoke of politics on the campus. He thought political parties had the right to set up branches in universities, but believed that the students’ union, the collective body that represented the concerns of all students, should be truly non-partisan.

Moving from the university to society at large, JP deplored ‘the precipitous decline in the standards of public behaviour’, the ‘growing indiscipline in all walks of life’. He felt that the blame for this ‘must be placed squarely at the door of the Congress Party’. They had been in power ever since Independence, and the slippage in their own standards of conduct had ‘set the tone for every other [form of] public behaviour’.

From the dominant political party in the India of the time, JP moved on to the dominant religion. Speaking as a Hindu himself, JP voiced his ‘serious concern over the state of the Hindu religion as it is found in practice’. For ‘some important sections of the Hindu community’, he pointed out, ‘piety or religiosity is only a means to obtain divine sanction for unethical behaviour, such as black-marketing, tax-evasion, profiteering, etc.’ Meanwhile, for ‘the mass of the Hindu people, the Hindu religion means nothing more than a few mythological tales, crass superstition, some taboos and observances’.

In this ritualistic, instrumental, practice of Hinduism, remarked JP in 1966, ‘religion as a formative, humanising, ennobling force hardly seems to have survived’. The ‘great movements of religious reform of the 19th and early 20th centuries have spent their driving force’, he noted, and ‘the outer dead shell of karma kanda is all that seems to be left of the Hindu religion, nothing or very little of the inner core’.

Read: 19th-century politics for a 21st-century society

In his travels around the country, JP found that it was ‘not uncommon to meet the catholicity of Vedantism in words accompanied with the most narrow-minded caste observances in deeds’. He added that ‘we talk glibly about the tolerance of the Hindu religion, yet do not raise an eye-brow when men, women and children are butchered for no other crime than of belonging to another religion’.

JP’s strictures were relevant when he issued them, and may be even more relevant today. As a Hindu, he saw the need to renew the life-affirming aspects of his faith. He worried that ‘the revivalism that is now taking place will push Hindu society further backwards, and may incidentally destroy even what we have of the unity of the nation’.

JP then remarked (accurately, in my view) that ‘the Hindu religion is a strange mixture of good and bad, the sublime and low, the most emancipated thought and the most bigoted obscurantism’. He thought that ‘what happens to the future of Hindu society depends upon which of these strains are to be selected and nourished and propagated’.

JP had started life as a Congressman. Even after he left the party, he retained a close personal friendship with Jawaharlal Nehru. Nehru’s daughter Indira Gandhi was prime minister in 1966, yet JP did not hesitate to remind his audience of how the Congress had contributed to the decline of public morality in independent India.

Read: How Narendra Modi resembles Indira Gandhi

JP was courageous in taking on the ruling Congress, and perhaps even more courageous in taking on the extremists of his own faith. He was speaking in the wake of the march on Parliament led by sants and sadhus, demanding a total ban on cow slaughter. That march had witnessed a greater deal of violence than had been seen in the city since the dark days of 1947.

What would JP have made of the gau rakshaks of today? He would surely have been appalled by them. I do not believe that JP would have been impressed either by the New Age gurus who now presume to speak for Hinduism, around whom flock upper-class Indians in search of personal consolation. In consorting with the rich and powerful, these gurus have done little to address problems of caste and gender inequality, which still so deeply disfigure social life in the India of 2016, as they did when JP addressed the students and teachers of Delhi University back in December 1966.

Ramachandra Guha’s books include Gandhi Before India. You can follow him on Twitter at @Ram_Guha

The views expressed are personal