India has become good at faulting Gandhi, and adept at not consulting him

Seventy years on, we have become good at faulting that old, tried servant of the nation, and adept at not consulting him.

Seventy years ago, as the year turned from 1946 to 1947, we were not yet a free nation but were becoming one. We were not yet a divided nation but were becoming one. We did not have a prime minister but we had someone who was becoming one.

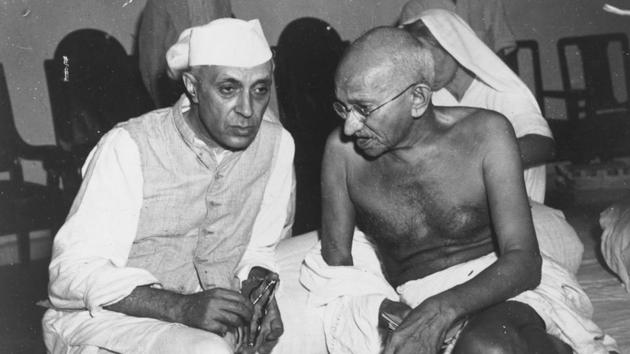

Described officially as vice-president of the Governor General’s executive council, Jawaharlal Nehru was PM-designate. But of a nation that he knew, as did Gandhi, was in the throes of a division. In the West, and in the East, of undivided India, freedom and Partition were in the air. With the worst massacres in recent memory having torn human beings apart in the eastern parts of Bengal and in Bihar, Gandhi was where the violence was, where the pain and desolation were. He was in the Noakhali region of Bengal.

In the first week of that December 1946, as Gandhi walked across East Bengal’s shattered villages, Nehru and Jinnah flew to London together, at the invitation of Attlee’s government, to find a solution to the great discord between the Congress and the Muslim League (ML) on the scope of the new Constitution. ‘The last ditch’ is a phrase that could be said to have been devised to describe that effort. Can an undivided India be saved? Jinnah was clear. For him saving undivided India from division was not the aim. Creating Pakistan was. Jinnah was as a clenched fist. Tight, firm. The talks, held over December 3 to 6 failed. London said it would not contemplate “forcing… a constitution upon any unwilling part of the country”. There was no chance for the talks to have succeeded. On the 6th, failure was officially announced and the two leaders flew back, Jinnah ebullient, Nehru in deep gloom.

Read: BJP attempt to obscure Nehru’s contribution to nation-building won’t work

On the 28th, he did what was the most natural thing for him. With Congress president Acharya Kripalani, he went to Gandhi, carrying with him his great burden of care, of worry. Fear he did not know. But gloom he did. He carried with him all his churning emotions to place them before the Mahatma, and seek from him the gift of some light in the dark, some hope in the hopelessness. He reached Srirampur around midnight and turned in to meet the Mahatma first thing in the morning. But the 77-year-old host was up by 2.30 am to check if the few rudimentary arrangements he had made for Jawaharlal in that little village had worked for the guest’s comfort.

No, he was told. Why? Jawaharlalji refused to have any special comforts made for him. Kripalaniji, likewise. But I had told you to, he up-braided people around him. What could we do, Bapu, when we told Jawaharlalji that Bapu has ordered us to give you these essentials he said: ‘Disobey him!’

Gandhi smiled at this. “That is Jawaharlal”, he said “so let it be”.

Read: A contemporary view of Nehru and Patel

Over the whole of December 29, Nehru gave Gandhi an account of the ML’s obstinacy at the London talks. He pleaded with Gandhi to leave Noakhali and return to Delhi so as to be there for the Congress and the interim cabinet to turn to, to consult. Gandhi was adamant that his work was where suffering was, Noakhali where Hindus had been slaughtered and Bihar, where Muslims were butchered. Nehru tried again, on the 30th. To no avail.

He had brought with him for his host, apart from the burden of his gloom and worry, a gift. A gift for the Mahatma? What gift – material gift – could Nehru possibly give to Gandhi and in that hour of the deepest darkness and sorrow, in the very heart of communal frenzy? And what is that gift that Gandhi would accept, not return or turn over for ‘public use’? It was, from the author of The Discovery of India, a pen, a fountain pen. The extraordinary Gandhi chronicler CB Dalal in his re-creation of Gandhi’s daily chronological sequence has a cryptic entry (in Gujarati) against December 28, 1946, Srirampur: “Jawaharlal and others came to meet. Gift of a fountain pen from Jawaharlal”. I have tried without success to learn more about that pen, its make, its present lodgement. I have not succeeded. Perhaps a reader of this column, a diligent researcher, archivist or a Gandhi museum conserver, will enlighten us about it.

Read: From South Africa to Israel, these roads and statues honour the Mahatma

I do not know but would like to believe that the following note to Nehru written at 3 am on December 30, 1946, was written with that new pen: “Your affection is extraordinary and so natural! Come again, when you wish, or send someone who understands you and will faithfully interpret my reactions…Nor is it seemly that you should often run to me even though I claim to be like a wise father to you, having no less love towards you than Motilalji….(But) somehow I feel that my judgment about the communal problems and the political situation is true…So, I suggest frequent consultations with an old, tried servant of the nation.”

On New Year’s day, as Gandhi left Srirampur he spoke to the villagers about his own shortcomings. “Point out my faults to me,” he told them. “Friends are friends only if they do that”.

Seventy years on, we have become good at faulting that old, tried servant of the nation. And adept at not consulting him.

Gopalkrishna Gandhi is distinguished professor of history and politics, Ashoka University

The views expressed are personal