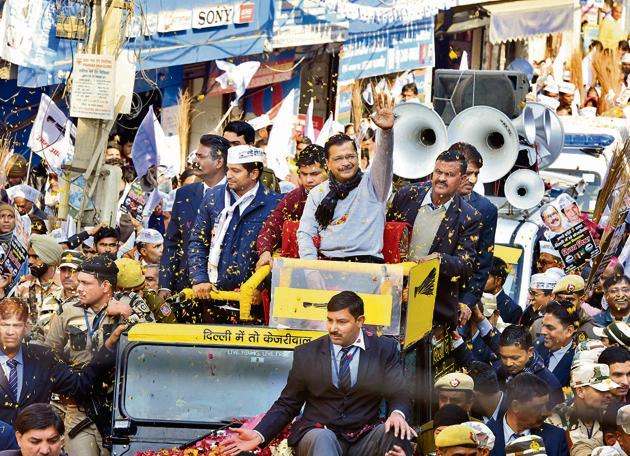

How Kejriwal avoided the trap laid by the BJP in this election, writes Barkha Dutt

The system has mellowed him. But the CM has also placed new political cards on the table

Arvind Kejriwal, tipped to have the advantage in the Delhi elections, has framed his campaign as being about “kaam ki rajneeti (politics based on work) ”. In an interview with me, he reiterated his argument that the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) was seeking votes on its governance record — on the schools it has turned around, on the slashed electricity bills, on its public healthcare schemes. This, he said, is “true desh bhakti or nationalism.”

Liberal pundits have been quick to seize on his campaign as an illustration of how the humdrum of people’s daily lives matters more to them than the rhetoric of religious polarisation. Their argument goes something like this: If AAP is able to defeat the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) after the unprecedented and aggressive polarisation attempts by the BJP, it is proof that Indian voters care more about economic well-being than they do about any other issue.

Yes and no.

It is true that the AAP’s mohalla clinics, its stellar commitment to raising the standards of government school education, and its offer of free or subsidised electricity appear to have won it the working class and lower-income vote for Delhi. So, yes, without that track record and model of welfare economics, this election would have been very different.

ALSO WATCH | Delhi Election 2020: ‘Hurt by BJP’S terrorist jibe’, says Arvind Kejriwal

But if you examine the Kejriwal campaign carefully, you will notice several tactical moves and shifts that indicate that Hindutva has not been disregarded as a factor by the strategists of the AAP campaign. And nor has the BJP’s strident attempt to own the nationalism space.

The recital of the Hanuman Chalisa by Kejriwal in an interview was no coincidence, for instance.

In the very last mile of the campaign, all the party candidates could be seen at temples in their constituencies, as also photographed while performing yagnas and poojas. Prashant Kishor’s team (which is working with AAP in this election) had clearly decided to take no chances. More than anything else, this was to empower AAP cadres with answers if confronted with the charge of being anti-Hindu, something the BJP has often accused its political opponents of.

Kejriwal’s deft sidestepping of the Shaheen Bagh protests against the citizenship legislation, and his virtual dare to Amit Shah to shut down the protests and open the road, is in keeping with this strategy. “I say schools, they say Shaheen Bagh, I say roads, they say Shaheen Bagh, I say hospitals, they say Shaheen Bagh,” said Kejriwal to me, thrusting the responsibility for handling the women-led vigil onto the home minister.

How he handled the tag of “terrorist” is also instructive. Not just did he see an opportunity here to convey a sense of emotional injury; he also used the slur to underline his nationalistic credentials. “I am a kattar deshbhakt ( staunch nationalist),” he said, “my political journey began with the Anna Andolan whose central slogan was Bharat Mata ki jai (victory for Mother India).” The patriotism curriculum in Delhi schools is part and parcel of this tactical refusal to let the BJP cast its opponents as anti-national. In many ways, Kejriwal has been consistently careful to avoid the sort of liberalism associated with progressives on the Left of the spectrum. For instance, he supported the effective nullification of Article 370 in Jammu and Kashmir.

Kejriwal calls his political style “authentic desh-bhakti.” It is much more nationalistic “to talk about schools and education than it is to constantly harp on Hindu-Muslim politics,” he says.

His popularity in Delhi has also been aided by his own transformation. He is clearly less impetuous and reactive than before. His politics may have been rooted in the belief that he was the clean “outsider” in a corroded system; but the system has mellowed him and taught him to hunker down and work and build relationships even with those he once used the choicest of words for.

You could call it the mainstreaming of Kejriwal. But he has still played a political hand that has placed a new set of cards on the table.

It would be a complete misreading of the AAP campaign to believe that its architecture has been built around an ideology stridently opposed to the BJP. It is also erroneous to think that this is entirely a bijli-paani election. After the Amit Shah-led BJP hitback made it clear that it would not allow that to be the framing of the polls, Kejriwal had to adapt and re-adapt. And though Kejriwal invited Shah to a debate with him after the BJP failed to declare a chief ministerial candidate, one of the cleverest things about the AAP campaign has been to avoid a direct rhetorical confrontation with its key opponent.

In the language of combat, it would be called avoiding the landmine. Stepping onto one can either freeze you or kill you.

Kejriwal has preferred a different route. To win the battle before the war.