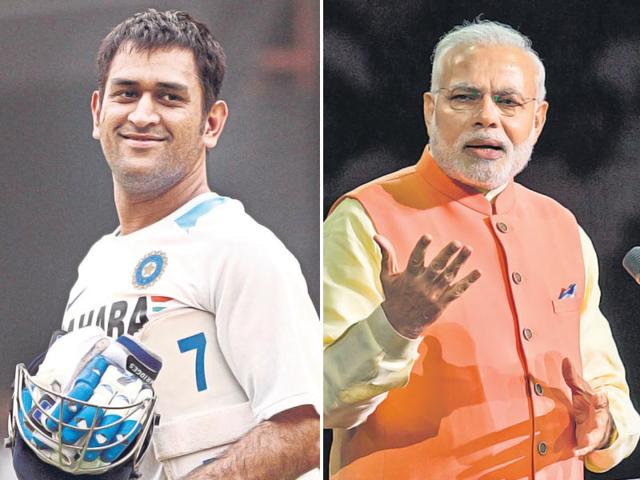

Fire in the belly: Both Dhoni and Modi are real gamechangers

Both Modi and Dhoni would probably be seen as the ultimate icons of the neo-middle class. The problem at times is that this class isn’t concerned about the means but only focuses on the end result, writes Rajdeep Sardesai.

You know a ‘small town’ boy has made it really big when he stays at London’s upscale Mayfair, when he has an office in Hyde Park, and leads a company with revenues of more than Rs 77,000 crore. Two years ago, while interviewing Anil Aggarwal, the scrap dealer turned billionaire head of Vedanta Resources, I asked him what his success mantra was. “Fire in the belly, when you live in a small town it comes naturally,” said the Patna-born businessman in less than perfect English.

I recall Aggarwal’s success formula while looking back at the life and times of India captain Mahendra Singh Dhoni on his retirement from Test cricket. There are various ways to assess Dhoni’s career. The easy way is to look at his achievements in pure statistical terms: Most catches for an Indian wicket-keeper, most runs as an Indian Test captain, a man who led India to a T20 World Cup win, victory in the 50-over World Cup, a rise to the number one Test team in the world. But to restrict the Dhoni legacy to mere statistics would do grave injustice to his persona. Dhoni is special because he, more than any other Indian cricketer before or since, has come to typify the ‘democratisation’ of Indian cricket, its spread from clubs and gymkhanas to every nook and corner of this country. Much like Aggarwal represents the triumph of Indian capitalism beyond the bright lights of Nariman Point.

Yes, before Dhoni there was Kapil Dev (like before Aggarwal, there was Dhirubhai). The ‘Haryana Hurricane’ was seen to challenge the dominance of the metropolitan elite over the sport, even bowling fast, something that was considered unthinkable in the land of spin. Dev, with his toothy smile and effervescent all-round skills, was undoubtedly a magnetic personality. And yet, he is, in my view, a transitional figure, someone who still belonged to a pre-liberalisation age when cricket still hadn’t fully discovered its commercial potential. It is with Dhoni that the circle is complete: He exemplifies the ultimate rise of the small town boy with a determined glaze in the eye and a feverish self-belief to a life of unimaginable riches and glory. Is it any surprise that it is in the age of Dhoni that the Men in Blue have addresses from Rajkot to Meerut?

In a sense, Dhoni is to cricket what Narendra Modi is to politics: A real gamechanger. Vadnagar, the prime minister’s home town, is much smaller than Ranchi: The capital of Jharkhand has a bustling city centre with its favourite son staring at you from neon-lit hoardings. Vadnagar is a dusty, sleepy, temple town that could easily fall off the map. If Dhoni’s cricket career was shaped on the matting wickets and bumpy maidans of Ranchi, Modi’s worldview was determined by the hard, unforgiving environs of Vadnagar. When you play cricket in Ranchi, or cut your political teeth in Vadnagar, then it’s highly unlikely that you will play by the rules set by the traditional elites.

Dhoni has been successful because he has refused to be cowed down by history or reputation. There is a delicious story, possibly apocryphal, of how Dhoni was once asked what he thought of Farokh Engineer, India’s original wicket-keeper batsman hero. “I haven’t heard of him,” confessed Dhoni. Clearly for him the past was dispensable; like many of this generation, he wants to live in the moment. Which is perhaps why he is such a fearless cricketer, ready to take a close match to the final over, convinced that he possesses the skill and power to win a game off his own bat.

In that sense, he is a bit like the prime minister, who Congress leader Jairam Ramesh once accused of playing “Bodyline” politics. In the 2014 elections, Modi changed the rules of election campaigning, defying conventional wisdom, which suggested that the BJP couldn’t win a majority on its own. If Dhoni would explode with a ‘helicopter shot’, Modi had his 3D ‘brahmastra’; if Dhoni has been tireless across all formats of the game, Modi too set a punishing schedule for himself. Both relish an aggressive approach to any contest, unwilling to take a step back when faced with a challenge.

Of course, there are significant differences too in style: Dhoni is a man of few words unlike the prime minister who is a natural orator. While Modi takes great delight in constantly being in front of the camera, Dhoni has preferred to shun the arclights, zealously guarding his privacy and choosing to switch off with a near Zen-like composure. And while Dhoni is seen to have been a genuine team-man, who could inspire both his younger and older teammates, there is still a question mark over whether the prime minister’s authoritarian style is suited to taking along his entire team with him.

Both Modi and Dhoni would probably be seen as the ultimate icons of the neo-middle class, a reference to the aspirational, post-liberalisation Indian who is looking to ride on the super-highway to instant gratification. The problem at times is that this class isn’t concerned about the means but only focuses on the end result. So, Dhoni’s supporters brush aside charges of ‘conflict of interest’ and even perjury in the Chennai Super Kings case as inconsequential just as Modi’s cheerleaders don’t see any reason for their leader to show greater remorse for his failures during the Gujarat 2002 riots. So long as Dhoni was delivering results on the field much like Modi has now mastered electoral strategy, little else seems to matter.

Post-script: I once referred to my late father, Dilip Sardesai, as the Dhoni of his generation in the 1960s. Born in Margao, he remains to date the only Goa-born cricketer to play for India. I remember asking him once why he thought he had succeeded at the game whereas I hadn’t. “Fire in the belly son, you big city boys just don’t have it!”

Rajdeep Sardesai is a senior journalist and author of 2014: The Election that Changed India