Choosing a Congress president, democratically, writes Ramachandra Guha

Rather than choose their new president behind closed doors, the Congress should consider organising a series of debates between candidates, conducted in Hindi and in English, and moderated by a television anchor who commands respect

I have just returned from two weeks in the United States, my visit coinciding with the primaries being held to choose the Democratic candidate for the next presidential election. Conversations with American friends were entirely about this topic, contrasting the relative merits of the candidates. In the evenings, in my hotel room, I watched television debates and town halls where candidates made the case for themselves directly. I was impressed by Bernie Sanders’ earnestness, Elizabeth Warren’s intelligence, and Peter Buttigieg’s charm, while Joe Biden’s track record was not to be scorned either.

While I was away, the topic of who might be the next president of India’s main Opposition party was being discussed at home. Some senior Congress Members of Parliament (MPs) had called for an election to decide the issue. Their voices were amplified by younger Congressmen in signed articles in the newspapers, who likewise thought that choosing a fresh face to lead it was the best way for India’s oldest party to renew itself.

These calls from within the Congress for electing a new president presumed a one-off event, with individual candidates putting themselves forward, and the 1,200-odd members of the All India Congress Committee voting. However, the example of the Democratic Party in the United States offers another and (as it were) more democratic alternative. Why can’t the Congress consider holding a series of televised public debates and town halls, where the candidates present their views and showcase their potential for leadership, before conducting a formal election restricted to party members?

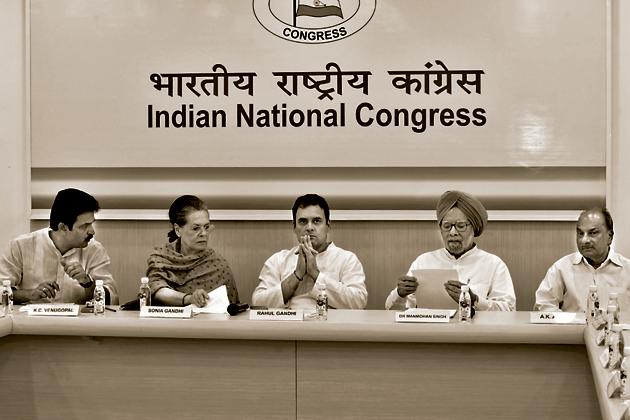

Before I say more about what such a process could look like, let me state two important truths about Indian politics today. First, general elections in India are increasingly presidential, and the person who so lamentably failed to take on Narendra Modi in 2014 and 2019 cannot hope to succeed in 2024. This, in itself, should rule out Rahul Gandhi resuming the Congress presidency, or his sister taking the job instead. For young Indians in particular detest family entitlement and privilege. I recently met with some 80 college students in Delhi, almost all of whom were opposed to the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP)’s majoritarian politics. When I asked who among them thought Rahul Gandhi could effectively take on Narendra Modi, not one hand went up in assent.

The second truth is that despite its decline in recent years, the Congress remains the only party apart from the BJP with a footprint across India. On the choice of its next president critically rests the hopes of the Opposition denying Modi and the BJP a third term in office. That is why it should choose its new leader on the basis of the widest possible consultation and the most transparently open process. The Democratic primary offers an excellent model to emulate, at least in its basic format, if not in every detail.

Who are the individuals who should or might put themselves forward for election as Congress president? A student from Odisha recently wrote to me suggesting the names of Captain Amarinder Singh and Shashi Tharoor. The first is an experienced administrator and former Army veteran; the second is formidably intelligent and articulate. A third possibility might be Bhupesh Baghel, currently chief minister (CM) of Chhattisgarh. His first year as CM suggests that he might relish the challenge of a larger responsibility. A fourth candidate could be Sachin Pilot, who played a vital role in helping the Congress win the assembly elections in Rajasthan, and who has been an MP and Union minister as well. A fifth could be Siddaramaiah of Karnataka, an entirely self-made politician with a strong connect to the rural masses, and vast administrative experience.

The five people listed above are all members of the Congress. However, the process suggested here would be made more meaningful if it were open to former members as well. I think, in particular, of Mamata Banerjee, who cut her teeth and made her name in the Congress, and left only because the old men of the party gave her no space to grow. If she could join the debate, and make the case for why she should take over the presidency of a once-again united party, it would make the debate more credible — as well as more colourful.

In fact, there is no reason why (following the model of the American Democrats) such a primary should not be open to those who have never been members of the Congress. Were (for example) a successful entrepreneur and a charismatic social activist to also throw their hats into the ring, the contest would become even more interesting.

Rather than choose their new president behind closed doors, the Congress should consider following the model suggested here. It should organise a series of debates between candidates in different cities, conducted in Hindi and in English, and moderated by a television anchor who commands respect, such as Ravish Kumar. The candidates would at the same time be free to state their case in one-on-one interviews to the press, in speeches on the stump, and in individual manifestos.

Such a process would take several months. Were it to begin soon, it could be concluded by the end of the year, three-and-a-half years before the next general elections. The winning candidate would have earned his or her victory in an open and transparent manner, giving him or her the necessary authority to lead the party. Perhaps the new president’s first priority would be to bring breakaway units such as the Trinamool Congress, the Nationalist Congress Party, and the YSR Congress back into the main party. The second priority would be to establish close and cordial relations with regional parties with whom it would wish to form alliances. Once these are in place, the Congress could concentrate on raising funds and building organisational capacity to fight the general elections.

It’s been fun writing this column, indulging in this thought experiment about how a once great, now moribund, party can begin to renew and reform itself. However, while the column may be read, I somehow doubt its recommendations will be acted upon.

Ramachandra Guha is the author of Gandhi: The Years That Changed The World

The views expressed are personal