Burden of farming outweighs rewards: Is India staring at another Nandigram moment?

Interventions such as loan waivers or MSP revisions can at best offer temporary succour. At worst, they deflect attention from the real issues behind the crisis that has been in the making for long

On March 14, 2007, when 14 farmers died in a clash between villagers and police forces in Nandigram of West Bengal over acquisition of land for an industrial project, few had imagined it would mark a turning point in the state’s politics. Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee of the then ruling Left Front in West Bengal had just stormed to power on the promise of reviving the industrial glory of the state, but Nandigram proved to be his nemesis. Overnight, farmers across the state turned hostile; the Opposition closed ranks; the intelligentsia distanced itself from the “bhadralok” chief minister and eventually, the Left lost the plot in a state it had ruled for 34 years.

Cut to 2017, the nation is perhaps staring at another Nandigram moment. The killing of six farmers in a police crackdown in Mandsaur in Madhya Pradesh earlier this month has put the spotlight on India’s worsening farm crisis. The farmers’ unrest that has since spread to other parts of Madhya Pradesh and elsewhere in India is a wake-up call. For it is a result of years of neglect of agriculture, something that still provides livelihood to two-thirds of the India’s 1.3 billion people.

Burden of farming outweighs rewards

At the core of the problem lies a growing mismatch between what it takes to grow food and what a farmer fetches for his produce in the marketplace. Economists explain this using the phrase ‘terms of trade for agriculture’, which improved for a brief period in the 1990s before turning unfavourable for most part of the new millennium.

Sample this: In 1992, a typical farmer in Punjab paid Rs 6 per litre for diesel are 10 times higher. In contrast, the minimum support price (MSP) of wheat, which is what most of Punjab grows, has increased only five-fold during this period — Rs 330 per quintal to Rs 1,625 per quintal.

Moreover, farmers in the past rarely spent much money on pesticides, to protect their crop. They do now, and pesticide prices have spiked more than the cost of any other input. Twenty-five years ago, farmers didn’t have to bore deeper every year to pump water into the fields. They do now, because water tables are dropping at an alarming rate.

In other words, the burden of farming has grown much faster than the rewards it brings. Demonetisation made it worse. As my journalist colleague Harish Damodaran wrote, “We’ve entered deflation territory in farm produce, whose proximate trigger clearly has been demonetisation.” Much of the trade in farm goods is cash-based and financed through a chain of intermediaries — wholesale buyers, processors and retailers. Demonetisation crippled this network of informal credit, causing a free fall in the prices of farm goods across the board.

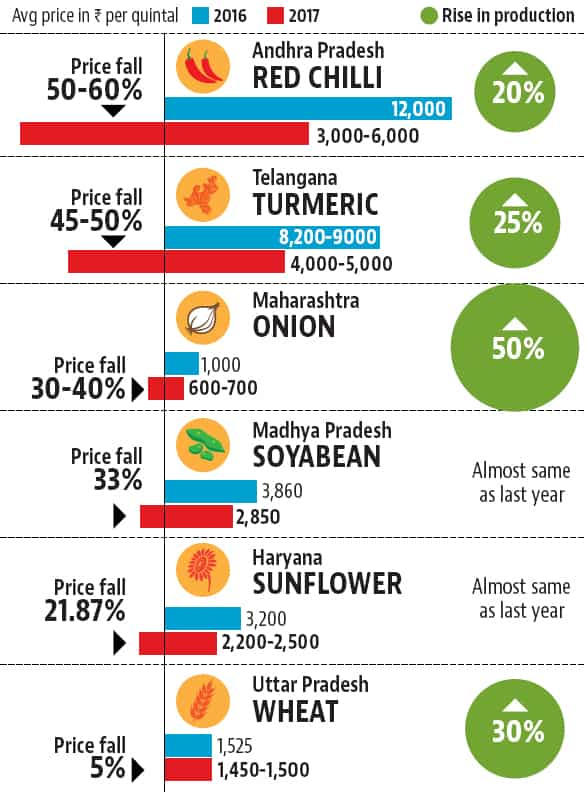

Like everywhere else, Mandsaur farmers were agitating after they were forced into distress selling. The prices are well below what they fetched in 2016: Onion for Rs 1 as against Rs 7, turmeric for Rs 50, half the price in 2016, soya bean at 33% lesser than the rate in 2016 and so on.

A bountiful harvest, which helped the broader economy post a somewhat impressive growth of 7.1% in 2016-17 despite a demonetisation-driven slump in manufacturing, had turned into a curse. What could have been an occasion for celebrations has turned into a season of mourning for deaths triggered by a glut in farm produce and their plunging prices.

As someone said, it is the worst time to be a farmer. A five-part series – Being A Farmer Now -- that will appear in this newspaper, starting Monday, brings out the depth of the despair that is sweeping farmlands across India.

Years of neglect

The imbalance between input costs and remunerative prices, however, is just one explanation for the growing farmers’ unrest. From sluggish infrastructure to lack of research breakthroughs, India’s farm sector faces many challenges. For most crops, yield per acre grew at a slower pace over the past one-and-a-half decades compared to the 1980s and 1990s. So did the expansion of the irrigation network. Successive governments have paid little attention to building research and institutional support to the farming community. As we speak the most premiere agricultural research institution, IARI, is into its third year without a full-time director.

The share of government spending in agricultural research and education in the gross domestic product (GDP) has fallen by almost half in the past 15 years – from about 0.5% to under 0.3%. Developed countries, which depend much less on agriculture, spend 2% of their GDP on agriculture. The figure is at least twice higher for even countries like China and Brazil.

The neglect of agricultural research has had a bearing on growth in farm productivity. In a well-researched article published recently in the Economic and Political Weekly, economist Shantanu De Roy demonstrates how, for most crops, yield per acre grew at a slower pace over the past one-and-a-half decades compared to the 1980s and 1990s. So did the expansion of the irrigation network.

Public investment in agriculture has been stagnant for nearly a decade, while private capital flows have not picked up enough to provide the stimulus that the sector needs.

From my reporting days in the late 1990s, I remember how the government built a narrative to defend its failure to invest enough in the farm sector. Foreign-returned economists, many of whom occupy positions of power, would twist data to show how private sector investment could more than fill up the gaps in public investment. It never happened. We know that now.

As a result, growth in agriculture has decelerated from an annual pace of 2.8% in 1990s to 2.4% through the decade of 2001-10 and to 2.1 % in the first half of the current decade.

What India’s farm sector desperately needs is a radical policy overhaul based on a new imagination. Interventions such as loan waivers or MSP revisions can at best offer temporary succour. At worst, they deflect attention from the real issues behind the crisis that has been in the making for long — India is reaping what it sowed as it scripted a story of economic transformation that left the farmers out.

Rajesh Mahapatra is the chief content officer, Hindustan Times. He tweets at @RajeshMahapatra