Spice of Life: View from the cockpit on sortie back to Kargil War

With the Line of Control having lost its relevance, many would realise that they had been lucky to return unscathed from ‘foreign’ territory. Some even landed with the enemy’s ‘autograph’ on their machines.

It was a hot summer afternoon and we were watching a World Cup cricket match. “This is the time to be in Kashmir,” said Paramjit, my closest friend in the squadron. Sometimes, a casually uttered wish comes to pass. That very evening, we got orders to mobilise. Thirty-six hours later, we were headed for Kashmir; Kargil War had begun.

New to the profession of flying with practically no hill-flying experience, I mostly co-piloted with experienced aviators. While these mavericks carried out unconventional flight manoeuvres, I looked out for enemy activity in air and on the ground. Our fighter jet and a helicopter had recently been downed by the enemy and we couldn’t let our guard down. “Sir, I see low clouds at the valley floor,” I once reported to the captain. “Dammit, that’s the enemy’s artillery barrage,” he made me wiser.

The pre-flight briefings spelt out our mission, the post-flight debriefing would make us wiser about the ground situation. With the Line of Control having lost its relevance, many would realise that they had been lucky to return unscathed from ‘foreign’ territory. Some even landed with the enemy’s ‘autograph’ on their machines. Evacuating the wounded with a sight of hope in their eyes was gratifying but carrying body-bags was disheartening; a dead man weighs as heavy in the aircraft as he does in the mind of the pilot.

The media had inundated the warzone and war scenes went live in everybody’s homes. Seeing those images, the nation was galvanised with nationalistic fervour which till then had been hijacked by cricket. Watching the bombardment of Tiger Hill became a bigger thrill than the euphoria after India beat Pakistan, kicking it out of the World Cup. A soldier on the front, however, seldom feels the same elation as a citizen does in front of a TV.

The moral support extended to soldiers by the countrymen was heartening. Restaurants and shops took pride in giving ‘army discount’ and donations poured in from across the country. People thronged in thousands for funerals of the unknown soldier killed in action.

Those fateful days were full of anxiety, uncertainty and anger. We prayed for the safe return of Flt Lt K Nachiketa, who had ejected and was taken prisoner; the enemy’s un-soldierly treatment to Lt Saurabh Kalia, was still fresh in our minds. Paramjit’s crash one day made me cry; thankfully he survived with minor injuries. The ceasefire was declared when the enemy was in retreat. Having lost over 500 men and more than double wounded, he certainly didn’t deserve any mercy; so we felt then in our twenties.

We returned to Jalandhar after the guns fell silent. Battle inoculated, I now saw life from a different perspective. The relief of getting back was, however, dampened; Paramjit didn’t return with us. Providence had come to his rescue when he crashed, but fate caught up three months later when he died due to carbon monoxide poisoning. Such is the fickleness of fortune.

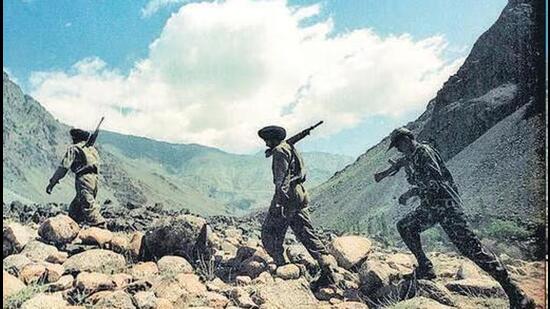

Twenty-five years later, I salute our hardy, patriotic and valiant soldiers who conquered those unforgiving heights against fearsome odds. Their victory resonated well with the codename of the operation: Op Vijay.

echpee71@gmail.com

(The writer is a Mohali-based freelance contributor)