Write moves

If roughly 30,000 words make a novel, at least 3,60,000 are crying, daily, for attention at the Rupa office in Daryaganj.

If roughly 30,000 words make a novel, at least 3,60,000 are crying, daily, for attention at the Rupa office in Daryaganj. The publishing house gets 8-12 unsolicited manuscripts a day, says its publisher Kapeesh Mehra. Sometimes they come wrapped in cellophane, in a gift-wrap packaging with a red ribbon, or in a grey bureaucratic folder.

Tanya, an editorial assistant, keeps a record of these. “A tango team of seniors and juniors (editors),” says Mehra, “sift through the heap.” The day may yield everything or nothing — the next literary diamond. Or, the duds. Nearly 100 writers offer their fiction to Harper Collins a month. Five years ago, that number was nearly half. Penguin, the first international publishing house to set up an India office, would get less than 100 manuscripts (MS). It gets 320 MS/month now. Rupa gets 120 unsolicited MS; five years ago it would get around 70. New entrants, Hachette and Westland, get 120 and 70 MS a month.

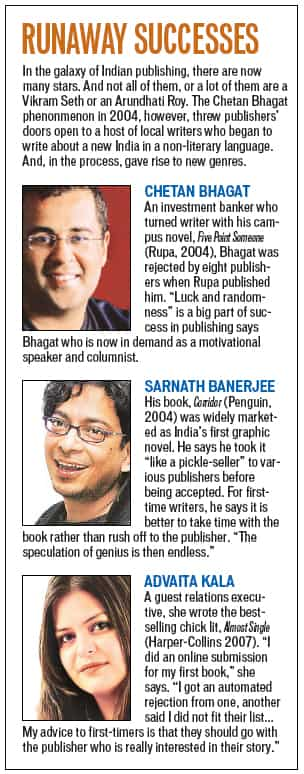

What’s making writing seem attractive to Indians? The fact that writers are now everywhere. The rise of the book launch and its sister act, the literary festival, as social dos. The growth of the publishing industry in terms of numbers (besides Penguin, there are 10 other major publishing houses to post MSes to). The presence of literary agents as an influential tribe (Aitken Alexander Associates will be the first British literary agency to open shop in India and there are more to follow). The traffic between media and the publishing machinery and the combined ability to turn an unknown-person-who-writes into a personality with a good headline, display, guest columns. “When so many new writers get published (see box Runaway Successes), it makes it seem easy,” says Saugata Mukherjee of Harper-Collins India.

STIR THE POT

Easy, it isn’t. Since the entry of literary agents in India at least 10 years ago, the slushpile in English language publishing is seen as the Great Void and a wasteland where words without legs, thought without depth, sentences without syntax, characters without reflection are set up by well-meaning desperados eager to write but unable to do so.

But as publishing is a business without guarantees (“Even terrific books die without a trace,” says Prita Maitra, managing editor, Westland Ltd), the conventional wisdom is this: the slushpile is a pot that must be stirred even if writers or books rarely emerge from it. Junior editors mostly cut their teeth on the pile. It’s not really a plum assignment. Paloma Dutta, assistant copy editor, Penguin, who monitors the slushpile every Friday looks at 40 manuscripts a day of which “only five or six can be passed on to commissioning editors”.

Mukherjee, a gentle demolisher of writerly illusions, breaks up the pain in stats: “Of the 200 unsolicited manuscripts, 95% cannot be read beyond the first chapter, only 5% make it to the second reading level.” Once, he made the mistake, he adds, of “writing back to an author whose work I had rejected saying his manuscript was ‘impeccably researched’, so it kept coming back to me in different avatars — with a new epilogue, new chapters, new heroes, new brothers of heroes, and even, to my horror, as a novel in sequels”. The Harper-Collins India managing editor also mentions being hounded on Facebook and ‘poked’ on why he “never responded even though the manuscript was sent to his office”.

A person well-known in Delhi’s party circles is on Kapeesh Mehra’s case to convince him that his 11-year-old niece is a prodigy whose kid-lit fantasy of “aliens marrying an Indian superman” should be a Rupa book. Everyone he meets these days, he says, has a manuscript.

WRITERS, SELLERS, READERS

Are we, perhaps, turning into a nation of writers? “I don’t think so,” says Urvashi Butalia, publisher, Zubaan, and whose initiative, Kali for Women, started with Ritu Menon, was one of the first independent publishing ventures in India. “Nor are we turning into a nation of readers…our per capita book consumption is one of the lowest in the world.”

If that is so, who is reading and who is writing? And why does everyone want to write? An uncritical approval of authors as people whose success is both the moral of the story and the ‘goal’ of publishing, has sent out mixed signals to readers, so much so that it is the latter who now knocks at the publisher’s door for entry. This is a Reader who doesn’t want to Read any more. He wants to Write. And the market has added to his confusion.

How? The Reader has seen that the pop and ‘high’ literature hierarchy can be reversed. A Meenakshi Madhavan book has equal billing with an Amitava Ghosh book. (Unsurprisingly, the random and personal banalities, views on relationships, life, pets, of 25-year-old ‘Arshi’ in books such as Reddy’s You Are Here is now being seen as literature — Stephen Dedalus and Joseph K go take a walk — as the ‘universal experience’ of an ‘individual’). The production values of both are the same. Advances for first-time writers of commercial and literary fiction are on a par.

Must PUBLISHING be ABOUT ECONOMICS?

“It all depends on the maths, as in how many copies we hope to sell,” says an editor adding that the readership has changed. “No one wants metaphysical explorations any more. Self-help books are more popular than Salman Rushdie.”Commercial fiction is the new baby that everyone’s looking to publish. “Booker-winning The White Tiger sold over 200,000 copies. Advaita Kala’s chick-lit Almost Single is not too far behind. It sold about 100,000. What does that say?” asks a publisher.

There are ways to buck the trend, says Nandita Aggarwal, publishing director, Hachette India, while admitting that “one has to put books that will sell to a certain point or number”. “Hachette does quality commercial fiction…. As with the film industry, it is possible to do good Karan Johars,” she says. “We invest in our commercial list to pay for our literary.”

Often the hurdle is money. Talking of the Hachette list of Indian fiction authors, Aggarwal says, “The average print run of a good literary book is sometimes just 5,000. If we go simply with our India list of authors, we would find it difficult to sustain ourselves.”

Prasanta Chakravarty, associate professor of English at Delhi University, who runs an online project called ‘Humanities Underground’ which is trying to stretch the possibilities of arts beyond skill-oriented courses, draws a parallel with the world of publishing. “The popular always helps to redistribute the classic,” he says. “This rush for chick-lit or graphic novels shows an interesting shift and may become an important marker of our times. But the point is about homogenisation. Young and old are often looking to merge in with the available, rather than look for possibilities. Don’t give up on James Hadley Chase, but read and publish the other stuff too.”

THE RIGHT PUSH

There are two kinds of writers who are getting rejected by English-language publishing. Those who can’t write. And funnily enough — those who can. Avant-garde literature by writers without agents/contacts do not have equal purchase in the publishing structure. Pulp, on the other hand, which has the pretension of being ‘high’ is easy to push into marketing slots than, say, a ‘Joycean’ novel.

So, here’s a question. Actually two. Has the entry of literary agents made publishers lazy? Is it possible that in the slushpile might hide a gem and no one has been looking because agents are considered reliable first filters of literary merit? Says Butalia: “The agents publishers deal with, with one or two exceptions, are non-Indian and therefore they (the agents), mainly offer Indian writers living abroad, or the occasional Indian writer in India…. Agents have a long way to go in seeking out unusual authors. The authors agents do offer are not necessarily those the publisher would consign to the slushpile, but often people who are reasonably well-known in one way or another — even if not as writers. For slushpile authors it is very difficult to get a look in.” In 2010, Penguin India, for instance, published one literary fiction from the slushpile and bought 10 from literary agents.

However, there’s hope in individual initiative. Maitra says she “still finds very good writers who mail her directly”. Aggarwal says she attends to lots of writers who write to her “out of nowhere”. What editors say

Part of the Hachette slushpile is, in that sense, online. "We have an online address," says Aggarwal. "In the ‘Publish with us’ section, we say ‘Send us’. We mean it."

Publishers and books editors are not the bad guys, but as the saying goes, to beat the system, you have to change the system. And to stand with change is a beautiful thing.