Woven in chic: Baxter's book talks about Indian traditional textiles

Contemporary Indian Textiles written by Maggie Baxter puts the spotlight on innovative designers, who are infusing traditional textiles with contemporary sensibilities.

In November 2012, while attending a great Indian wedding, Australian art curator, textile artist and author Maggie Baxter was surprised to see her 35-year-old artist friend "who loved to shock" people with her dressing sense. Though usually seen "at the experimental end of Western" this time around, Baxter's friend had people agog with a sari bearing an 'African' design, topped with her tattoo-revealing, razor-back blouse.

The amazing sari as Baxter recounts was none other than the humble, Dhakaborn jamdani. A quintessential traditional Bengali fabric, with geometric motifs instead of the traditional floral pattern. The scintillating sheer weave at the hands of Kolkata-based independent design label bai lou, founded in 2002, had a contemporary makeover. This has made the nine yard garb appeal to modern Indian women such as politician Sonia Gandhi, her daughter Priyanka and actresses Tabu and Vidya Balan.

Known for its labour-intensive weaving patterns, the jamdani textile has been metamorphosed by 42-year-old husband and wife duo Bappaditya and Rumi Biswas, founders of bai lou and designers trained from National Institute of Fashion Technology and National Institute of Fashion Design respectively. They entwine tiny silver sequins within two layers of fabric to create what they call a Latitude sari. "We wanted to give the sari an embroidered look. My wife, Rumi, sat down with the weaver and his wife with a crochet needle and taught them how to make a sequin yarn," says Bappaditya. This ingenious technique earned the duo The UNESCO seal of excellence for Handicrafts award in 2006.

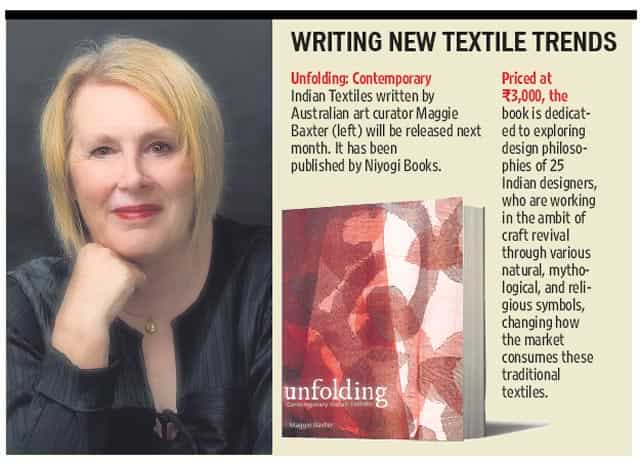

Baxter, 64, in her book, Unfolding: Contemporary Indian Textiles, has written about 25 such design labels in India that are reinvigorating the traditional textiles of the country such as bandhni, leheriya and jamdani, by giving them a new and an appealing identity in the world of contemporary designs. "These are not just making heads turn but are also re-interpreting tradition in a new mould," says Baxter, in an email interview.

The book is dedicated to exploring the design philosophies of these designers and artists who are working in the ambit of craft revival, minimalism, surface decoration, textures, and narratives through various natural, mythological, and religious symbols, changing how the market consumes these traditional textiles. These include the Delhi-based Raw Mango, Play Clan, Gaurav Jai Gupta for Akaaro, 11.11/ eleven eleven, Aneeth Arora for Pero and Goodearth and Noida-based Abraham and Thakore, Kolkata-based bai lou and GreenEarth.

"The book is an unprecedented effort as it is likely the first major document to record and share the more recent and exciting period of Indian textile design," says textile historian Rahul Jain. "From the late 1990s, we have seen a huge surge of younger textile and fashion designers bringing to the field a far bolder, and much more individualistic, creative expression. There was a clear need for a book like this."

The book takes shape

The journey of the book began in 1990, when Baxter first visited Gujarat. She was trying, unsuccessfully, to manufacture some bed linen and decided to try to produce some of it off-shore from Australia. On a friend's recommendation she visited India. "I fell in love with the place and textile crafts there," says Baxter. "It was strange really because back then I had no interest in crafts at all. At art school I majored in sculpture, focussing on installation art and photography. This did not equip me for block printing!"

In September 2012, Baxter initiated research on the idea of the book as she had been noticing the growth and emergence of young designers who merged tradition with the contemporary, a trend that she herself has been part of for the last 25 years.

With meagre information available on the topic, she admits her initial research depended on "going to designer shops and fashion weeks and then checking out designers online. I did get a lot of recommendations and then I would look them up online," says Baxter. She had also banked upon her 70 visits that she had made to India from 1990 to 2014, as well as five that were solely dedicated to the book.

Eventually between May 2013 to 2014, she sat down structuring the book on the lines of techniques like survival and revival, re-view, surface, texture, minimalism, narrative and inter-disciplinary crossover highlighting how each design label approached traditional textiles with a different design philosophy.

New-age players

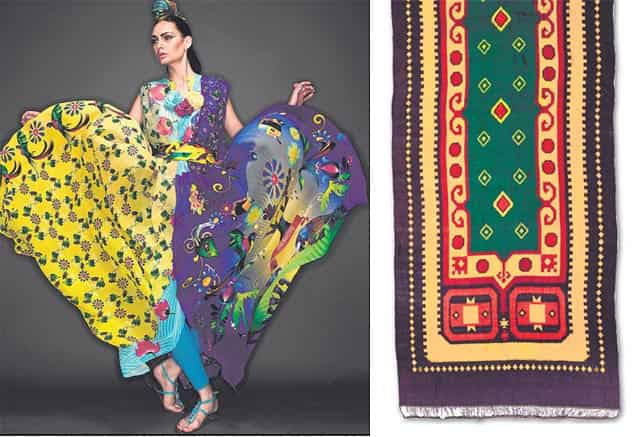

Edgy and popular, Play Clan is an example that has a loyal urban following with its brand of everyday subculture tweaked by a digital mix of design and art. "Play Clan has funky digital prints and embroideries, (which) are derived from life in villages across the country, whether it is in Nagaland, the Konkani coast, Rajasthan, or old Delhi," says Baxter. "Its founder Himanshu Dogra, 42, hand draws scenes from village life then scans them to digitally manipulate them. These are then printed onto silk, wool or canvas. He works with a small group of male embroiderers just outside of Delhi," adds Baxter.

From L to R: Play Clan’s Chitrahar sari is a medley of digital prints derived from traditional textiles; designer Kirit Dave’s Kilim sari uses ikat in a distorted and pixellated manner. (Photos: Niyogi Books)

This sense of design sensibility is percolating down to the artisan too as organisations like Kala Raksha Vidhyalaya Design Institution, in Kutch, by textile scholar Judy Frater, make the craftsmen understand the needs of the new-age consumer and train them to create their own designs rather than just working as artisans for established brands. Twelfth generation craftsman, Abdulaziz Alimohammad Khatri, 37, from Bhadli village in Kutch is one such craftsman. Working with the international design team label, 11.11/ eleven eleven Khatri has learnt to combine bandhni, Japanese clamp-dyeing and block printing.

"In 2006 I enrolled at Kala Raksha on my father's suggestion, without knowing what they teach," says Khatri. "We never knew what to offer to the client before. When a foreigner would come asking for bandhni, I would present colours like bright green and orange without knowing that those do not appeal to their sensibilities. Now, adept at design and market needs, I along with my brother Suleiman Khatri, 40, have exhibited our 'modern' and 150-year-old designs in Lucknow, Mumbai, and Delhi."

Another prominent designer in the field is fashion and textile designer Gaurav Jai Gupta, 33. He weaves the fabric with stainless steel wires and crystals, on a handloom. "I am an advocate of slow fashion. I prefer the handloom as opposed to the power loom as I don't feel the need to reproduce unnecessarily when the planet is already clogged with so many products," says Gupta.

"I have learned several technical aspects of design under Gauravji," says Gopal Basak, 54, one of the craftsmen who work for Gupta. "When I was working with my father I had never imagined that I would someday weave electric wires," adds Basak, originally from Fuliya, Nadia district in West Bengal. The threads of rural culture and fate of artisans run through all traditional textiles of India, says Baxter, "India has a stronger connection to its material culture than any other country with textile production and embellishment, being second only to agriculture in rural areas as a means of income - and many are living close to or under the poverty line. Therefore design intervention as a means of producing new markets is essential first to improve income and secondly as a means of survival of the craft tradition," adds Baxter.