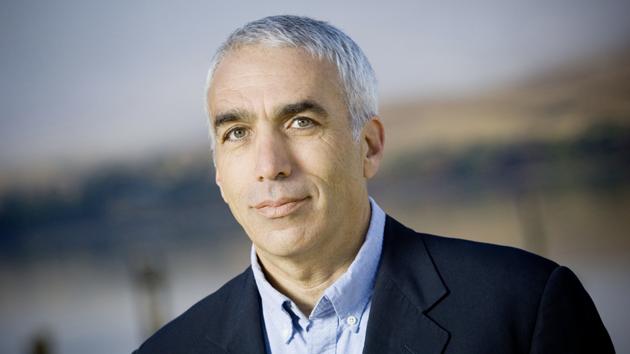

We must change our understanding of people who’re addicted: David Sheff

The Beautiful Boy author on the implications of pushing addicts into depths of seclusion, the need for better reform structures and his latest book The Buddhist on Death Row

It was after the release of David Sheff’s book A Beautiful Boy: A Father’s Journey Through His Son’s Addiction, in 2008, that many in the world understood the wider implications of addiction and the drastic impact it has on the individual and his/her family. The author says pushing them into the dark corners of the society, further alienates them and that needs to be understood. “We must change our understanding of people who are addicted. We must learn and teach others that the addicted aren’t bad people who lack morals and will power. They aren’t people making bad, selfish choices, because addiction isn’t a choice - no one wants to be addicted,” says the author, whose book was adapted into a film starring Steve Carell and Timothee Chalamet.

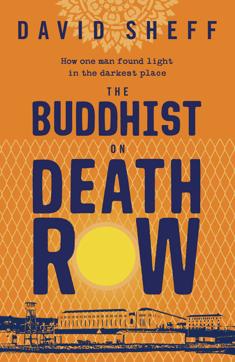

In his latest book The Buddhist on Death Row, he discusses issues related to “race, social justice, criminal justice, and spirituality,” which come together in the story of a death row inmate he was introduced to. Excerpts from the interview:

How did the idea of ‘The Buddhist on Death Row’ come about?

I’ve been interested in issues related to race, social justice, criminal justice, and spirituality, and they all came together in the story of a death row inmate I was introduced to. His name is Jarvis Masters, and he was a friend of a friend. She’d become a supporter, working to prove his innocence. Not only did she speak about his case, but about his life in SanQuentin where he’d been on death row for 30 years, 22 of those years in solitary confinement. It felt incongruous to hear her say that this man was the most remarkable person she’d ever known kind, loving, wise. He helped her in her life and others in theirs — all of which was extraordinary if you consider that he lived in a tiny cell in an institution with 3,500 other men convicted of some of the worst crimes imaginable. So, I went to meet him and I researched his case. The evidence clearly shows he’s innocent, but his appeals move through the courts at a glacial pace.

I’ve been interested in issues related to race, social justice, criminal justice, and spirituality, and they all came together in the story of a death row inmate I was introduced to. His name is Jarvis Masters, and he was a friend of a friend.

When I met him and returned over the course of several years, I saw what his friend described. Masters has every reason to be bitter and angry, but he is open and funny and joyful and kind to others. He’s written books that have helped people, including kids in gangs and growing up in violent homes. The more I learned about his life — he’d been, as he described himself, “a thug” who’d become a Buddhist teacher — the more intrigued I became. I saw how his story was one of forgiveness, injustice, suffering, and healing. It’s why I decided to write about him. I was a hard story to tell because a person’s spiritual journey isn’t outside but internal. Over the course of the years writing the book, I had to learn how to describe the very subtle and incremental process of how people can change.

You have worked as a journalist for years, how has that experience helped you choose and study your subjects? Has that experience made you a better writer?

Working as a journalist for years has helped me hone my interests. I’ve learned that writing a book is a commitment of years— years in which you are immersed in a subject and the people in your story. Because of that, I’ve learned to be very careful choosing a subject. I’ve reversed courses on books — rejected them — when I realized I didn’t want to spend years with subjects who were base, selfish, and cruel. Instead, I wanted to spend time with people who inspired me and who I could learn from and others could learn from. Since then, I’ve chosen my subjects very carefully. And it’s not only that I’m conscious of the kinds of people I’ll be writing about, but choosing a subject comes with a very big question about whether the story is worth telling given the world in which we live. It has to have meaning and importance - otherwise why do it? The point was driven home when I wrote Beautiful Boy. I wrote our family’s story to help process the experience in our family when my eldest son became addicted to drugs, but the book opened me up to a world of people suffering with addiction and mental illness. I realized the ubiquity of the problem and scope of the damage. In addition, I learned about the inadequacy of the system to provide care for people with addiction and mental illness and to support their family. I fell into writing about a subject that was meaningful to many people who often felt alone in their suffering. I realized that writing can help expose social injustice, drive progress, and support people in dire need of support. I realized that I wanted to only write about subjects with the potential to help people.

The stigma around addiction is the greatest obstacle we have to helping these people who are ill. It makes it harder for people to get into treatment. They’re shamed and made to feel guilty.

Even with A Beautiful Boy, you had cautioned that addicts need care and support as much as they need rehabilitation assistance. In countries like India and many around the world, the practice of looking at them purely as a criminal exists widely. How does one go about changing that perception that the society has?

You’re so right that we must change our understanding of people who are addicted. We must learn and teach others that the addicted aren’t bad people who lack morals and will power. They aren’t people making bad, selfish choices, because addiction isn’t a choice — no one wants to be addicted. No one wants to commit the crimes and participate in other bad behaviour that’s often associated with addiction. People who are addicted do things they’d never do if their brains weren’t in some ways hijacked by drugs. So we must look at them with understanding their condition — that they suffer a brain disease — and treat them with compassion and, recognizing they’re ill and need medical care not judgement. They need to be treated with addiction medications, behavioural therapy, peer support, and other evidence-based treatments. The stigma around addiction is the greatest obstacle we have to helping these people who are ill. It makes it harder for people to get into treatment and succeed in treatment. They’re shamed and made to feel guilty. When we realize that addiction can happen to anyone — no family is immune — and realize it’s not a choice — substance use disorders are recognized as psychiatric illnesses — we change our perception of those who are afflicted. We stop blaming them and judging them and their families. Instead, we can offer our compassion and they can enter a treatment system based on science, not prejudices.

They did make changes — for example, Steve Carrel, who plays me in the film (and yes, that’s weird to have the actor who plays Michael Scott in “the Office” play me), one night goes out to try the drug crystal meth because he wants to see what his son is experiencing, and I never did that .

How has your life changed after Beautiful Boy? By now, you have a fair experience of film adaptations. What do you make of it, since many authors feel a book should retain its power of propelling imagination...

I was reluctant to agree to a film adaptation of Beautiful Boy. Authors are often disappointed when Hollywood takes their stories and makes them into something else entirely, but this was even more risky. Beautiful Boy isn’t a story made up by a fiction author, it’s a memoir of my family’s very real experience. Deciding to trust someone to take that personal story and make a film was a long and careful process. Our family decided to go forward after talking a lot about it and meeting with the filmmakers — the producers had made other great films (12 Years a Slave, Moonlight, Selma) and they and the director and actors committed to showing the experience as it was — not a watered down Hollywood version of what happened. I still worried, of course, because whereas I was able to control every word in my book, the filmmakers had license to take our story in whatever ways they chose to. They did make changes — for example, Steve Carrel, who plays me in the film (and yes, that’s weird to have the actor who plays Michael Scott in “the Office” play me), one night goes out to try the drug crystal meth because he wants to see what his son is experiencing, and I never did that — but overall the movie reflects the emotional experience we lived, and I’ve heard from many people that watching the movie helped them. It was a revelation for themselves and their families. After seeing the movie, people talked openly about subjects that had been hidden in the past. It even got some people to ask for help and get help for their addictions and other mental illnesses. It also brought many families closer together. For those reasons, the experience of having my book and my son Nic’s book Tweak adapted as a movie was very positive and rewarding.