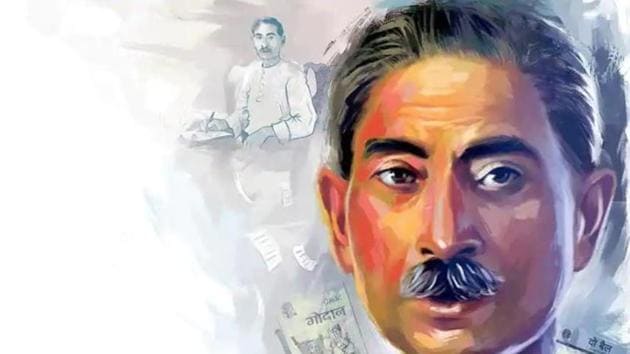

The Way We Were: Premchand’s lost months in Bombay

To mark his 140th birth anniversary, a look at the writer’s move to the city, and why he left it in less than a year.

Premchand arrived in Bombay on 31 May 1934. He was 54 years old, married with three children, the country’s most famous living Hindi writer – and a man in dire financial difficulties. The losses were piling up at the Saraswati Press he’d been running since 1923; and his two weekly publications, Hans and Jagran, were bleeding money. On the eve of his departure to Bombay, he wrote to a friend, “A drowning man was extended a hand, and has grasped at it.” The helping hand was the offer of a one-year contract by a film company, Ajanta Cinetone – a somewhat urgent, persistent offer, they sent him two telegrams -- to write stories for films, for which he would be paid eight thousand rupees. (He was so hard up, he didn’t even have money for the fare to Bombay – his ever-resourceful wife Shivrani Devi gave him one hundred rupees that she’d saved.)

But Premchand left Bombay in less than a year.

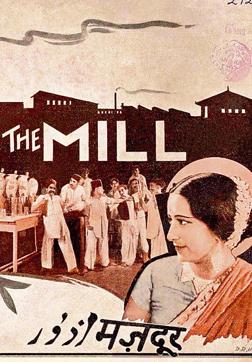

What happened during that time? On the occasion of his 140th birth anniversary (which was on 31 July), it’s worth looking at this singular chapter in Premchand’s life for a number of reasons. For one, much of what he said about the film industry rang eerily true for decades. Second, the fate of the one film he worked on is dramatic enough to merit a story of its own – and indeed has been studied by both film historians and Premchand scholars. Mill/ Mazdoor, Ajanta Cinetone’s realistic film about the clash between a dissolute mill owner and his workers, was banned across the country by the British government. And finally, there was Premchand the writer’s own personal journey -- his Bombay stint revealed what should have been a foregone conclusion. This very simple man who lived for his sahitya and came from the highly literary milieu of Banaras, found no happiness in either the commercial world of Hindi films, or a big impersonal metropolis.

Shivrani Devi recounts how Premchand didn’t sleep the night before the journey to Bombay, afraid he would miss the train which was at the unearthly hour of 4am, and also because he was upset at the prospect of going alone. Shivrani Devi was not accompanying him -- she had two weddings to attend in Allahabad; he would finally go to fetch her only in July. But she felt a serious pang at his departure too, and in her book, Premchand Ghar Mein, about her life with her famous writer husband, she describes how, after he left, she went up to her room and wept for one hour.

Soon after he arrived in Bombay (it was a three-day long train journey those days), he wrote to her, grumbling about how he felt so alone and lonely. (“It is a very fine place, with clean roads and airy houses, but I don’t like it here.”) He rented a three-bedroom flat in Dadar for fifty rupees a month and ate his meals by himself at a nearby hotel.

Two books -- Amrit Rai’s biography of his father, Kalam ka Sipahi (translated into English by Harish Trivedi), and a literary biography by the man often referred to as ‘Premchand’s Boswell,’ Madan Gopal -- recount Premchand’s Bombay days, while Shivrani Devi’s account provides several illuminating and endearing domestic details of his stay there.

Given his work ethic, Premchand diligently went to the studio every day. He was writing Mill/Mazdoor, and working with the German-trained director Mohan Bhavnani. Talkies had come to India three years ago (Alam Ara, 1931), and after a predominance of mythological and devotional cinema, it was now time for the social film.

Mill/Mazdoor fell in this bracket: A mill owner leaves his textile mill to his son and daughter. But the son is a debauch without a care for workers’ welfare. His sister, the exact opposite, is in love with a mill worker, and leads the workers in a strike against her brother.

Premchand was persuaded to play a cameo and the film was shot on location at a cotton mill, unusual for the time.

About Mill/Mazdoor, Premchand wrote to his friend, the Hindi writer Jainendra, “I can say, it’s mine, I can also say, it’s not mine…. The director is all in the all in the film industry. The writer may be the master of the pen but this empire is that of the director.”

When the film went to the Censor Board to be certified, it faced outright rejection. Apparently, Byramjee Jeejeebohy, president of the Bombay Mill Owners Association and, incidentally, a member of the Censor Board, was the man behind the decision. Luckily, the film was cleared for release (with one cut) by the local Censor Board in Punjab, but on the first day itself a crowd of almost 60,000 workers arrived at the theatre, and massive crowds continued to turn up throughout the first week. The police and army were called in and the Punjab government banned the film. A similar fate befell Mill/Mazdoor in Delhi when – inspired by the film -- a mill worker lay down in front of an owner’s car! Eventually the government of India banned the film altogether. Though – in keeping with Premchand’s Gandhian views -- the film advocated peaceful protest against the mill owner, and stood for amicable partnership between the striking workers and owner, it was considered too dangerous. Also, it depicted the mill owner in an unflattering light, as a violent man who sent thugs to break up the strike and generally spent his time drinking and womanising.

The film’s unhappy fate in some way mirrored Premchand’s own less-than happy life in Bombay – though he now had his anchor, his wife, with him. Shivrani Devi describes his routine in the city: he would go for a walk at five in the morning, eat breakfast by 7.30, then repair to his room to work. Often, visitors would drop in at this time. After lunch he would set off for the studio. And he would work on his book late at night. Sometimes, when she woke up at two or two thirty at night, she would see the light burning in his room. Even so, he wasn’t making much headway with the novel (Godaan). He had also started smoking too much and his health, always delicate, had begun slipping. By December 1934, he was fed up. He wrote to a friend: “I had come into this line as I saw in it some prospects of achieving economic independence, but I can see now that I was mistaken and I am returning to literature again.”

He also had his own rather uncomplimentary assessment about the film industry: “It is useless to expect any reform in Hindi movies... Those who control it… are concerned only with profit.” He called it “a great money-making machine.” In his words: “I had gone there with certain ideals but I found that the cinema people have certain readymade formulas and what lies outside those formulas is taboo.” The guiding principle of the film industry was to produce what the consumer wanted. Though he did believe that the public wanted to see other stories too – stories of love, sacrifice and friendship. But when films were full of “naked dancing” and “public kissing,” there wasn’t much hope!

Despite the fate of Mill/Mazdoor, Ajanta Cinetone offered another contract to Premchand – they wanted to send him to England for a year, as part of their plans for expansion, and pay him ten thousand rupees for four or five stories. But Shivrani Devi wouldn’t hear of him going overseas. Himanshu Rai of Bombay Talkies also made him an offer, but by then, Premchand had had enough – of the movies, of film writing, of the city. He longed to be back in Banaras, working on his novels and short stories, close to his sons who were studying in Allahabad, surrounded by his like-minded literary friends. (Madan Gopal writes that there was also an offer to edit a Hindi daily in Bombay, but Shivrani Devi put her foot down.)

It wasn’t surprising that Ajanta Cinetone or Bombay Talkies wanted to offer contracts to Premchand. There was his fame as a writer of course. But there was a more basic issue here. After talkies were introduced, the industry needed Hindi writers and lyricists. In a city dominated by non-Hindi speaking people, it was natural that the writers would come from the north, particularly UP – the United Provinces as it was called then. (In a letter to Jainendra, Premchand wrote that the people he dealt with knew neither Hindi nor Urdu. “I have to tell them the meaning of the story by translating it into English.”) Many of the writers and poets who came stayed on and carved successful careers for themselves; many left after short stints.

By the third week of April 1935, Premchand was back in Banaras, where he finally finished Godaan, his last masterpiece. Though financial problems continued to dog him, he soldiered on, as he always had, right up to his death in October next year. And what of Mill/Mazdoor? The print cannot be found; the film is lost forever.