The mother’s milk of politics; Review of ‘When Crime Pays: Money and Muscle in Indian Politics’ by Milan Vaishnav

Milan Vaishnav’s engaging book points out that India’s main weakness lies in the mediocre quality of the state and its eroding institutions

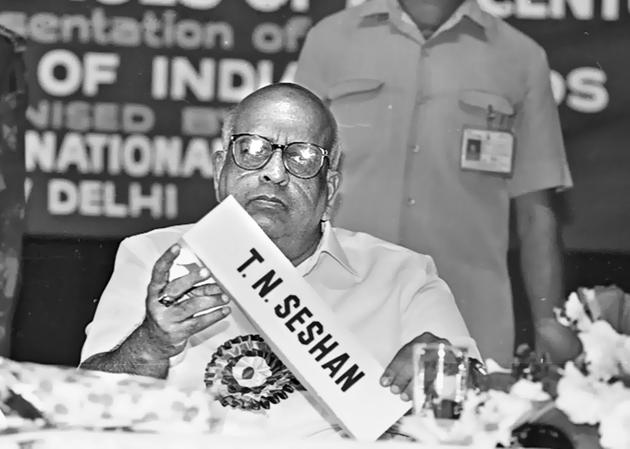

India’s electoral apparatus is a crucible of democracy. Its eventful journey had two watershed moments: First, when TN Seshan took over as the Chief Election Commissioner and transformed the institution between 1990 and 1996, and second, when the Supreme Court ruled in 2003 in a petition filed by the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) that all candidates will have to disclose their assets, qualifications and details of criminal cases pending against them.

Seshan earned the nickname Al-Seshan (or Alsatian for a watchdog!) for his audacious orders. Thanks to him, the election code of conduct -- which was a bit of a joke until then – began to be taken seriously. Manipulations by ruling parties became tougher and bribing and intimidation of voters, at best, went underground. The ADR case was a huge leap forward because it created new benchmarks of transparency. Today, the Indian norms allow the disclosure data to be accessed, verified and used by anyone, including rivals, cops and academics.

Vaishnav has done a splendid job of this data evolving his own tools of analysis based on methodologies being used by the best global and Indian institutions. He has complemented his meticulous data work with insightful ethnography. The writer has crisscrossed the country interacting with candidates, their henchmen, polling officials and ordinary voters. It is this field work done on campaign trails in the hinterland, which makes the data come to life, making the book highly engaging, even amusing in parts.

The author connects the dots to establish a clear line of causality in the way political power is negotiated. He highlights the system of incentives in the game of thrones and their cost to democracy. And the phenomenon is not restricted to any particular caste, region or religion. It’s absurd that the law-abiding citizens should elect serious criminals, with their eyes wide open. It is even more shocking when they do so by beating reputable rivals. One can censure the political parties who field them in the first place but what about the choice that the voters make by electing and re-electing the dons?

The book’s central thesis is that there is a market logic of demand and supply of criminality. The approach goes beyond the bechara matdata (poor ignorant voter) hypothesis. For instance, the voters could be looking for extra-legal tactics for their community’s protection or for a smooth delivery of benefits. The book theorizes the crime-politics nexus in the framework of Francis Fukuyama’s moral and practical requirement i.e. of a system which balances between an effective state, norms of accountability and the rule of law. India’s main weakness, the writer argues, could lie in the (mediocre) quality of the state and its eroding institutions.

The lack of inner democracy in India’s political parties, or no culture of holding primaries, helps perpetuate the anomalies. Vaishnav upholds the US democrat Jesse Unruh’s view that money is the mother’s milk of politics. The ‘bad candidates’ are always handy in cross-subsidising their lesser-endowed brethren. Their presence is secretly heart-warming for the party bosses whose pockets get lined in the process. “Wealth and criminality have an interactive effect: wealth significantly magnifies the electoral success of criminal candidates,” he concludes. The writer follows the cash trail but stops short of shedding light on India’s black economy which fuels its dirty politics.

Read more: Sasikala saga shows crime-politics nexus has no regional bias: Milan Vaishnav

Can anything be done about stopping law breakers from being law makers? Vaishnav cites many reasons, ranging from institutional stagnation to governance deficit to cronyism and the new interplay between modernization and corruption. While there are no short cuts the remedy lies in fixing an array of regulatory, extractive and political rent-seeking activities, reining in political parties and cleaning up their finances, amending electoral laws and rethinking democratic accountability. Until then, it will be sadly business as usual.

*Vipul Mudgal heads common Cause and Inclusive Media for Change project