Spies, crime, profit: Poet Arjun Rajendran’s new work is inspired by diaries from the 18th century

The diaries left behind by Ananda Ranga Pillai, right-hand man to the French governor of Pondicherry Joseph Francois Dupleix, shine a light on the intrigues and everyday life of the time.

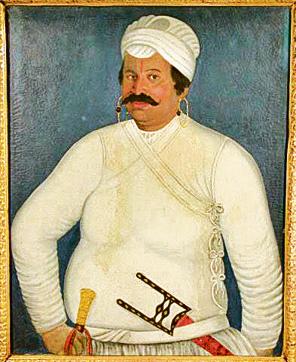

One evening about a year ago in Puducherry, a moustached man stared down from a painting at poet Arjun Rajendran. This was Ananda Ranga Pillai, the right-hand man of Joseph Francois Dupleix, who in the 18th century was governor of the French colony.

Five years earlier, Rajendran had been tipped off by his father, a history buff, about the 12 volumes of Pillai’s diaries (dating from 1736 to 1761) available on digital libraries like archive.org. They could make a great subject for poetry, his father had said. By the time the poet encountered Pillai in a museum, his “Pondichéry” poems, mining the dead man’s diaries, were nearly done.

One Man Two Executions was published by Westland in October. The title is taken from a poem in the collection. “At that time, it was a tradition that, during a hanging, if the noose snapped, the criminal was thought to have been forgiven by God and would be set free. In this poem, a priest supervising a hanging overrides that unsaid rule and orders that the man be hanged again,” Rajendran explains.

In this book, as poet and writer Jerry Pinto puts it in his blurb, “the spectres of the past are given flesh and blood.” This is Rajendran’s fourth volume of poetry. “Pondichéry” is the first of its three sections. It evokes the 18th century through various interlinked poems that explore it as a place of culture and grime; conspiracy and friction; murder and subterfuge. Or, as the poet says, “a place quite like today”.

Rajendran worked as a business analyst in the US for 12 years; he returned to India in 2016, eventually settling in Pune. He’s founder of The Quarantine Train, a poetry collective, and poetry editor of The Bombay Literary Magazine, an online quarterly.

For a living, he teaches French online and edits manuscripts. “What matters to me is that every poem I write should, in style and subject matter, stand out from my previous work. A fascination for the paranormal, history, science, the occult and pop culture have largely influenced my work,” he says.

Here then is a window into the society, customs and manners of a forgotten time in Pondicherry, through Rajendran’s poems.

Dubash Ananda Ranga Pillai

Dubash, a Hindi word for someone who knows two languages, actually means an interpreter. Pillai knew Tamil, French and Persian. This skill made him an invaluable member of Dupleix’s coterie. Pillai was from a well-connected upper-caste business family. “As Dubash, he entertained dignitaries; read letters that were passing between the different power players — from the Danes to the Marathas and Mughals. As the chief of espionage, he intercepted letters from the British. He had a finger in many pies,” Rajendran says. His diaries are full of what he did, but he kept a tight lid on his own emotions. The poem, Dubash’s Gift, written of a time when Pillai is past his prime, has Pillai thinking of why “his reflection doesn’t know him anymore”.

Cheseaux’s Comet

Pillai’s diaries and Rajendran’s poems highlight the excesses of those in power, the social divides, and the violence meted out to people who don’t toe the line. In such a climate, a six-tailed comet is seen through spyglasses in Pondicherry. Rajendran’s poem, Cheseaux’s Comet, suggests that this out-of-the-ordinary event in 1744 was “considered an omen”, one of the first signs of a reversal of fortunes. Within 10 years, with Dupleix’s departure in 1754, the French would begin to cede ground to the English. “Indians, however, would still be at the mercy of an arbitrary, colonial power,” Rajendran says.

Sanctum Sanctorum

Rajendran channels a 1747 defilement of a temple in Pondicherry for his poem Desecration. The back story — refuse from a church is thrown into a temple, allegedly at the behest of the governor’s wife, Madame Dupleix. In a twist of irony, the poem captures how this was the only time lower castes gained entry into the temple. Not as devotees, but as cleaners. “This incident is taken from Pillai’s diary, Volume 3. He expresses outrage at the desecration,” says the poet.

Hungary Water

This was the popular perfume in Europe before Eau de Cologne. In the poem, Rise, and Begone to Thy House!, a low-caste Christian convert wears it to church: “At the altar she kneels…unaware that Hungary Water is intertwining its scent with holy water”, only to have the priest insult her. “The caste divide, as Pillai noted in his diaries, was rampant and continues even today,” says the poet. Another poem, Lunar Eclipse, notes about another church that there were “pews meant for the left-hand”, meaning lower castes.

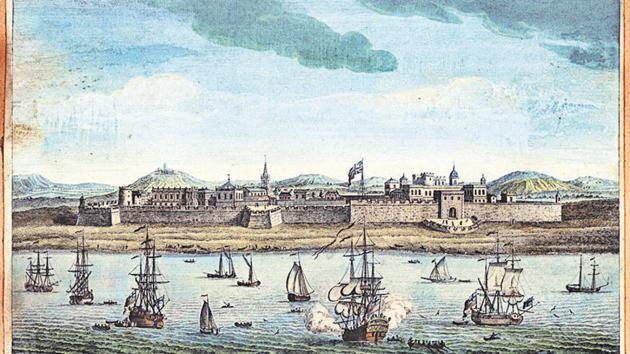

Men at sea

For those who wanted a career at sea, a lascar’s was a decent job to have. These were sailors employed on European ships from the 16th to the 20th centuries. “The Lascar’s Wish is a poem in the collection where I do insert myself in an 18th-century setting,” says Rajendran. “In the poem, I am the lascar. I imagine a girl I’m in love with being kidnapped.” In another poem, Who Buys from the Slave Dealer, another lascar gets 50 lashes for stealing pepper. “This was the age of the sail,” says Rajendran. Ships were synonyms for merchandise, adventure, new ideas. “In the 18th century, the Coromandel coast was one of the richest places on earth. Everyone wanted to try their luck here.”