Shabana Azmi: “I’ve been phenomenally lucky from the beginning”

After a performance of Kaifi Aur Main in Bangalore, Shabana Azmi talked about her parents, her 50-year acting career, being socially conscious, balancing art and activism, and the objectification of women in the film industry

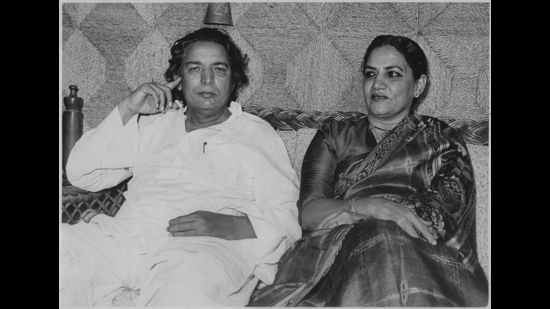

Everyone loves a love story. But what makes Kaifi aur Main, the love story in question, even more appealing is that it is told by the daughter of the couple whose story it is. Shabana Azmi plays her mother, Shaukat Kaifi, in Kaifi aur Main written by Javed Akhtar and directed by Ramesh Talwar. Kanwaljit Singh plays Kaifi Azmi, while the music, designed by Kuldip Singh, is brought alive by Jaswinder Singh and a team of musicians. Every song in the play is a reminder of how little we know the poets behind the classic Hindi film songs we adore. The sparse design of the play allowed for an expansion of the inner world of the two characters – one, a poet, communist and freedom fighter, and the other, a girl smitten by him. It is in her voice that we hear Shaukat and Kaifi’s love story complete with parental objections, secret supporters, love letters written in blood and bold acts of rebellion.

After a performance in Bangalore, Shabana Azmi talked about marriage, inequality, and the objectification of women, among other things.

As a child born of such a love as we see in the play, what does love mean to you? How has it manifested in your life? How do you cope with the hurdles it invariably brings?

Both my mother and father were very loving parents. When you get such unconditional love from both parents, like my brother Baba and I were lucky to get, it makes you very secure. You learn by example from your parents. My father was a feminist. And because we grew up in a Communist Party of India (CPI) commune, we lived in a small space with shared amenities. We were brought up by all comrades. Everybody was a working person. The reversal of gender roles was organic. When my mother was touring with theatre, it was my father who would take over. I grew up taking this for granted.

Only when I was about 19 did I realise that this is the exception, not the rule. I noticed that there is so much disparity between men and women. I saw how deeply rooted patriarchy is. That remains my biggest struggle – whether in the education of the girl child, in Mijwan Welfare Society (the non-profit my parents founded) or Nivara Hakk – a collective of slum dwellers’ groups and grassroots organisations that I was involved with. But the thing with love is – I have a lot to give and have got a lot in return. I’m not talking only about love for work, communities or romantic love. I’m also talking about friendship with girls – all of that.

I got married rather late in life. I couldn’t have married anyone other than Javed because we share the same world view. Plus, he is also a feminist. As you grow older you realise that love comes from friendship. That’s what I value the most with Javed. We have our arguments and differences but we also have two magic words if something threatens to become ugly. Either one of us will say – drop it. It has saved us from the worst fights. I believe that love from a relationship like a good marriage can be very sustaining but if you have only that to give to, then the burden becomes too much.

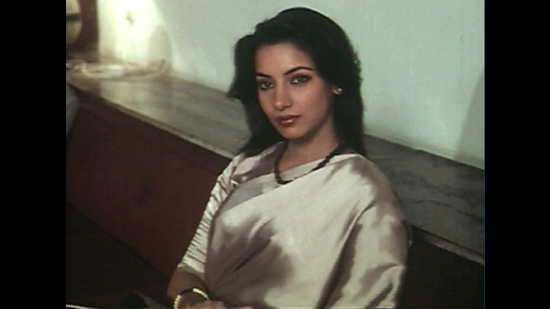

You’ve spent five decades in the film industry and assayed powerful roles. Do you pick your roles carefully? And how do you care for yourself in this line of work?

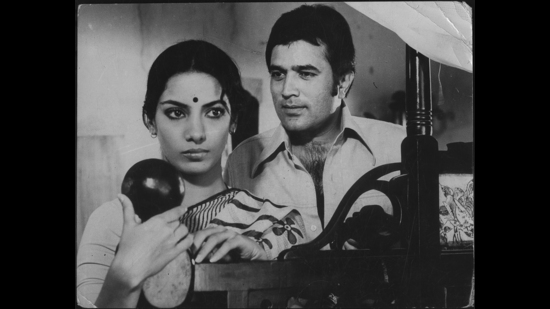

I’ve been phenomenally lucky from the beginning. I came out of FTII with a gold medal for acting. I didn’t have the period of struggle that new actors have. My first released film, Ankur, was the seedling for what came to be known as parallel cinema. It got me national and international recognition but was not a conventional role.

Later, I started doing mainstream cinema because I felt it was important to become a star in the commercial sense and get audiences, if they like me, to come and see an art house film too. At one point, I was working on 12 films at once! Only 12 because we were banned from working on more (laughs)...

When I was working in Raghavendra Rao’s Kaamyaab, singing “Dhakkam dhakka hua, pyar ka rang pucca hua” with Jeetendra in interior Andhra Pradesh, I was also working on Goutam Ghose’s Paar with Naseeruddin Shah, in interior West Bengal. I don’t know how I worked simultaneously in both worlds – so separate and demanding such different approaches. I hadn’t thought about it. It was very instinctive.

Speaking of self-care, in mainstream cinema, the most painful part is waiting endlessly for the hero to arrive. When I once grumbled to my mother, she reminded me that I am contracted to the producer to be present on time. So, I’d show up and wait. In the hour it took to travel to another set for the next shift, I’d have to choose between a nap and lunch – invariably choosing the nap.

Then, I started carrying other work to the set. There were no personal vanity vans. I’d sit reading, writing letters, managing my schedule on the set. I don’t remember it driving me crazy. I just accepted it. I’d read a lot of fiction (I loved short stories – still do) but after I got involved with the feminist movement, I read Simone de Beauvoir and Kate Millet. It kept changing when I got involved with other activism.

You’ve grown up in the intersection of the arts and activism, having watched your parents’ involvement in both fields. How do you balance both?

At one point, the filmmaker Aparna Sen (also a very dear friend) told me that my off-screen persona is becoming so large that it’s affecting my image as an actor. I thought about it but there was no way I could keep away from my work as an activist. I was even told that my face has become very stern. I studied my face and found truth in that. I had to work on softening my face.

Once, the police issued a laathi charge during a protest that I was in. I felt responsible for how badly the protestors were beaten. I went home and wept, resolving never to put others’ lives on the line. The next day, when a group of people from that slum came to me, I apologised with great trepidation. They said, “we came to check on you because there was blood on your kurta.” They urged me to continue to stand with them. “Your presence makes our voice get across,” they said. Another time, I was shooting for Brij’s Mardonwali Baat. It had been so difficult to get Dharmendra, Sanjay Dutt, Jaya Prada and me together for that shoot. I got news of an overnight eviction in a slum I’d been supporting. I was beyond myself, and sobbing, when I went to Brij and asked to leave. I was so surprised that a mainstream director understood and said he’d manage the day’s shoot without me. I finally found the evicted slum dwellers on the city’s fringes, coping in ways only they could. The communities I stand up for teach me resilience and strength. It is not me giving to them. It is they giving to me.

We see how objectified a woman’s body is in the film industry. Being a senior actor, how do you cope with this?

Making choices about films that were showing women in a derogatory light was never difficult for me. I’d refuse and they’d say, “Aap nahi tho koi aur kar lega,” and the film would get made (often even becoming a hit). Yet, I continued to work on films like Amar Akbar Anthony, which were not sexist – they were just having such glorious fun.

I was very upset about item numbers because when you show only a swivelling hip or heaving bust, you take away female autonomy and subject a woman to the male gaze. It’s not the same as celebration of sensuality. To show women in any degree of complexity was only left to art cinema. We need to show complex working women, which a large number of Indian women are. Change has to pervade men’s mindsets too – they currently take it for granted that they are the centrifugal point of a film.

Regarding safety... When I was in Singapore, I remember walking back well past midnight to my hotel and feeling, “This is what the feminist slogan ‘take back the night’ means!” What happens when women are harassed is that society tells them, “Stay home. The world is not your place. Why did you even get out?” Deep patriarchy is responsible for this and it can’t go overnight but efforts towards it should be made in every way.

How has your process changed as an actor over these five decades?

It has gone through many changes because I was initially a huge follower of Stanislavsky. When there were particular characters I was playing, I’d go and actually observe them. Technology has changed a lot in cinema, however. Now, you’re acting all on your own with nothing around you. It’s a different technique. Though it’s disconcerting, I like to embrace the new.

How do you compare working in front of the camera to being on stage as an actor?

The energy of a live performance is unmatched. Film, however, is collaborative and you can’t take credit for a successful performance because so many people contribute to it.

When you find something challenging in your work now, which are the films you think back to?

That would be Morning Raga and Arth.

For Morning Raga, I had just 18 days to prepare to play a Carnatic singer. Never having learnt music before, I was very frustrated and nervous. I’d spend the day in Parliament (being in the Rajya Sabha then) and do riyaz in the evening. It was deeply satisfying when it worked out well. I like being able to perfect a new skill in my work.

I look back at Arth when I have to touch raw emotions. When you’ve worked for so many years, there are few situations you’ve not done before. To keep the honesty alive is important. Arth brings me back to that.

Charumathi Supraja is a writer, poet and journalist based in Bangalore.