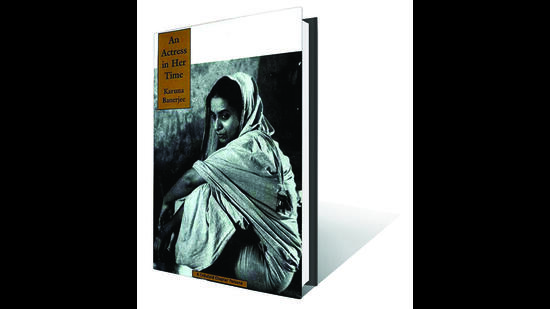

Revisiting An Actress in her Time by Karuna Banerjee

Few know that the actor who played Sarbajaya, Apu’s mother in the first two films of Satyajit Ray’s Apu Trilogy, was also a talented writer. This collection of her articles, essays and reminiscences includes a sketch of Mrinal Sen, a piece on films and their link to life and society, and memories of working with Ray

Karuna Banerjee would have celebrated her 104th birth anniversary on December 25. Who is Karuna Banerjee? She is the actor who is still identified with Sarbajaya, Apu’s mother in Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali and Aparajito. This, despite the fact that she did other notable films, including Kanchenjungha and Devi by Ray himself. Among the very few female actors who were college graduates at the time, she stepped into Ray’s first film after marriage and motherhood.

Few know that she also wrote. In 1999, Celluloid Chapter, a publishing house in Jamshedpur first brought out An Actress in Her Time, a collection of her articles, essays, and reminiscences written in English culled from magazine clippings and newspaper archives. Around the same time, Thema brought out Sarbajaya, a collection of Banerjee’s Bengali writings – short stories, nostalgic pieces, articles on cinema and interviews.

An Actress in Her Time includes 28 fluid and highly informed pieces written between 1959 and 1990. Among these is an interview published in the Indian Express, an unpublished letter to Dileep Padgaonkar in response to his editorial in the Times of India on the student agitation in response to the Mandal Commission, and a paper presented at an international seminar held during the Third International Film Festival in Delhi in 1965. The paper discussed and was titled The Film as a Reflection of National Life and Culture. Banerjee’s writing was published in a wide range of periodicals including The Illustrated Weekly of India, Filmfare, Mainstream, Readers Magazine, One Nation Chronicle, Close-up, Secular Democracy, Communicator, Amity and Youth Times.

This variety underlines her passion for writing. The fame of the outlet did not matter, the writing did. Her writing preceded her short acting career, and had she wished, she could have become a well known journalist like her husband. However, for her, writing was a means of expressing the Self, rather than a means of making a living.

Thumbing through the book, the reader finds her responding and reacting to films, television, and their link to life, society and more. Apart from memories of her experience of enacting Sarbajaya in two parts of the Apu Trilogy, there is a brief sketch of Mrinal Sen too:

As a film director Mrinal Sen is a disturbed man, for he is socially aware. He is keenly aware of his surroundings, the discrepancy in social levels, the conflicts and contradictions in social relationships – and all this creates a deep stir in him, a desire to explore and experiment. He is not a popular director and not a single producer has cared to finance him for a second time, for none of his films has been a commercial success.

She had worked in just one Mrinal Sen film, Interview. Yet, her insight into the director is one with which everyone will agree.

In the paper that she presented at the seminar during a film festivals, she says:

The film is as much an art as a reflection of significant social movements. At times, it is even a creator of such movements. In our country, it is also playing a vital role and can be employed more purposefully in the context of our developing economy. The total cinema audience in our country is estimated to be fourteen hundred million. Films set fashion for music, songs, clothes and even behaviour patterns.

Karuna Banerjee’s writing shows that she was devoid of the arrogance sometimes associated with film personalities. Recalling her experience of working in Kanchenjungha, Karuna writes:

Twenty years ago it was not the most natural thing in the world for a woman from a middle class family to act in a film. It was not a comfortable thought for me either; and I tried hard to wriggle out of the whole situation. But disowning all conventional norms my husband and my in-laws became great enthusiasts for this venture. They regarded the whole proposition as an interesting experiment.

About the famous Safdar Hashmi street play, Halla Bol, she writes:

After seeing Halla Bol in action, it struck me that a street theatre can justifiably be put in the category of a moving and speaking political cartoon. Its power lies in the instant rapport that it produces between the audience and the performers. In fact, this audiovisual satire has many dimensions, while an illustrated cartoon generally has one.

Her subjects were not limited to the performing arts. A few eloquently descriptive pieces are on her sojourns abroad and comment on lifestyles and landscapes. Here is her description of a trip to Russia:

Sochi is like a hill station, with gradual slopes going high up or deep down and a mysterious mist playing hide and seek with the sun. Thick woods surrounded the parks, lit up with a profusion of tulips of many colours, but predominantly glowing red. I was surprised to see a lot of bamboo groves, which we have in plenty in India.

It would be a fitting tribute to her memory to close this piece with a selection from her unpublished letter to the editor of The Times of India, which was immediately returned with an unsigned, printed regret memo. Written on September 28, 1990, the letter stressed on the “wholesome points” of the Mandal Commission and stands out for its prophetic tone:

The whole of India is like the battlefield of Kurukshetra at the moment. I am not going into the question of who are the Pandavas and who are the Kauravas, who is Krishna and who is Arjuna. Yet, the similarity is too glaring to be missed.

Shoma A Chatterji is an independent journalist. She lives in Kolkata.