Review: The Viceroy’s Artist by Anindyo Roy

The novel, based on Edward Lear’s journal, successfully brings to life the English nonsense poet’s year-long sojourn in India

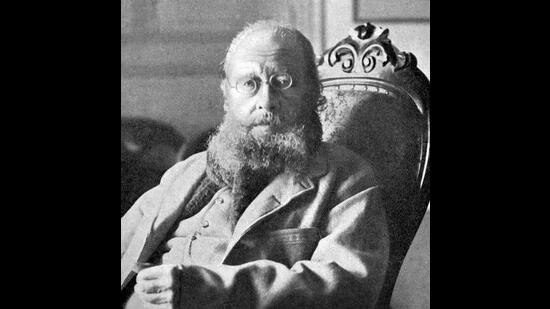

Edward Lear, the 19th century English poet and painter, has been commissioned by the Viceroy of India, Lord Northbrook, to paint the majestic Kanchenjunga. Lear, the author of A Book of Nonsense (1846), arrives with his Albanian servant Giorgi Kokalis in Bombay in November 1873. After diagonally “traversing the belly of India” on trains, pony carts and jampans, he reaches Kurseong, which, arguably, offers the best view of the Kanchenjunga.

Far away from the world of drawing-room niceties, the 61-year-old overweight and asthmatic Lear quickly settles into the world of kitmutgars (servants) and kamsamahs (butlers), and is both fascinated and repelled by the colonial rulers. Simultaneously, he tries to deal with his recurring episodes of indigestion and epileptic fits, which he refers to as “the morbids”, and unhappy memories of his poverty-stricken childhood and unfulfilled relationships.

Anindyo Roy successfully brings to life Lear’s little-known India sojourn, which lasted a little more than a year, based on the artist’s Indian Journal, published 70 years after his travels. Roy showcases Lear as a compassionate man whose imagination and curiosity knew no bounds.

Roy’s own journey towards fictionalising Lear’s travels is quite fascinating. Eight years after he first encountered the India Journal, the writings continued to haunt him. His obsession with Lear peaked during the pandemic lockdown and he decided to turn the journal into fiction to fill in the gaps of Lear’s “fragmentary observations, incomplete stories”.

Midway into his writing, Roy began to explore another half-hidden layer. “…I sensed that this extraordinary man – a world traveller, poet and painter known for his wild imagination and unconventional humour – was also an individual perplexed and shaken by his troubled past,” he writes in his Afterword. Roy then employed the stream of consciousness technique to capture Lear’s buried memories and desires. He successfully “untie(s) the knots, loops and tangles… allowing the silences to speak”. Perhaps this is why The Viceroy’s Artist isn’t an easy read. The nearly 300 pages seem much longer as there is no plot line, and there is too much back and forth between the many people

who starred in Lear’s life. Besides, the subject is at that stage of life, where he likes to replay fond memories in his head, and fret about, among other things, unrequited love. Roy holds forth on Lear’s love life – on his lady love Gussie, who was over 20 years his junior, and his man crush Franklin Lushington. While Lear was fascinated with Gussie’s handwritten fairy tales and her love for the mythical, he could never make up his mind about Lushington, whom he described as “inhabiting an abode of dust and air”.

It takes a while to settle into the many flashbacks, the scenes from the past which Lear wants to erase from his memory, yet they descend unannounced throughout his travels in the subcontinent and overwhelm him. Initially, they centre around Lear’s sister Ann, who was more than 20 years his senior and like a mother figure to him. She was the eldest among Lear’s 21 siblings. He faintly remembers his own mother placing a tattered shawl over a shattered window pane to keep the freezing air out. It would be replaced after their father returns. If father returns.

Even Giorgi, who belonged to “the vanishing species of trustworthy servants”, understands that his master’s quest is for something deeper than sketching the perfect view of the Kanchenjunga. Often, Lear, who spends his time contemplating the beauty of landscapes and mountains and entertaining self-doubts, does not want to be burdened with artistic challenges such as questions of angles, shadows and depths. Will his sketches be able to capture the middle ground on paper through all the blurriness, and preserve it for posterity? Will it satisfy the Viceroy -- who has paid him five hundred pounds for the assignment?

Roy’s lyrical writing and his intensive research into colonial India and into Lear’s life kept me going. Lear’s wry humour was an added bonus, and it made me ignore the meandering prose that was, in hindsight. needed to delve deep into the artist’s life.

The author’s main area of interest is imperialist literature. This comes through in his brilliant portrayal of the British Raj – from the perspective of the colonisers and the colonised. When visiting the heart of Britain’s Empire – Delhi – he cannot ignore the devastation caused during the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857. He finds himself trapped in this strange place where he empathises with the colonised and is irked by the coloniser.

Upon arrival, he promptly ticks off pompous British officers who boast about their military feats and wonders if Mrs Le Mesurier, a military officer’s wife, bore any actual resemblance to the photo that her husband dutifully carried. He confuses and distracts an officer who insisted “…the loftiest measured mountain in the world now belongs to England!” by chanting the names of the flora and fauna of Darjeeling and then stepping up his attack by spinning nonsense tales about strange phenomena in nature.

However, he loved their children. He regaled them with his stories and limericks, and sometimes penned a story or two especially for them.

Apart from the littlest details of Lear’s travels across India’s narrow and dusty roads in bone-rattling pony carts that gave him recurring backaches and knee aches, or on trains that seemed to stop at every station, Roy dwells on the world of the English memsaabs. One such memsaab, Lady Penelope, recommended a local, Nunkoo Lal, as a guide because she “appreciated his good English, excellent manners, and impeccable personal hygeine”, even as another memsaab complained to Lear about the insolence of her servants – “Just you

wait and see their expression when I look away”.

Nothing misses Lear’s eyes. Not the sandstone walls, gateways, domes and latticed verandas or ugly icons of “Britishized beauty”. Lear detested the neo-Gothic or Indo-Saracenic monuments as they were all “wrong” and “completely and utterly out of place”. He preferred “the wilderness, palaces and ruins” of India as they provided the “most astonishing spectacles ever, without any embellishment”.

Lear is credited with popularising if not inventing limericks, and Roy treats the readers to some of them: “Shadow and Light on a see-saw, Flinging their hands high up in the air. When not doing their classroom sums, they roamed the forests, soundlessly and without a care.”

My favourites included Lear’s wordplay such as ‘indy-gestion’ for indigestion in India and when he composes nonsense poetry with a uniquely Indian flavour. The poem titled The Cummerbund has “dobies”, “punkahs”, “kamsamahs” and “kitmutgars”.

Quite a few real-life characters, some friends of Lear, figure in the book -- Alfred Tennyson, Lord Northbrook, Maharaja Duleep Singh and Lockwood Kipling. Queen Victoria, who took on Lear as her tutor, finds a mention time and again.

The Viceroy’s Artist is a beautifully written and superbly researched book and should be on the must-read list of anyone who enjoys reading about the British Raj.

Lamat R Hasan is an independent journalist. She lives in New Delhi.