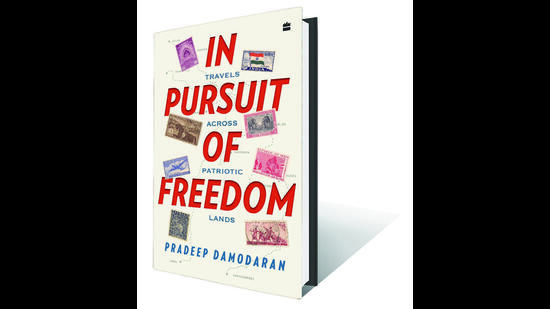

Review: In Pursuit of Freedom by Pradeep Damodaran

Travelling from Sabarmati to Champaran, Tentuligumma and beyond, Pradeep Damodaran combines history and on-ground reportage to present a picture of contemporary India

In February 2022, author Pradeep Damodaran visited the Sabarmati Ashram in Ahmedabad. One of many visitors, he looked at Hriday Kunj, the home of Mahatma Gandhi and Kasturba between 1918 and 1930, and walked through the museums and photo galleries. In the visitor’s book, he read an entry that hoped Gandhi would rot in hell. “Even after 75 years of Independence, still we are crying, dying because of you, Mr Gandhi. I realised why BABASAHEB BR AMBEDKAR did not call you Mahatma. Because of you, more than one crore people died during partition. Only soldiers dead in Kashmir as of today’s count is 90,000!’ The author adds in parentheses: “No idea how he arrived at this figure”. When the comment was pointed out to Atul Pandya, director of the Sabarmati Ashram Preservation and Memorial Trust, he said that the freedom to criticise Gandhi was exactly what the man had fought for. “Let them try to openly criticise today’s leaders and see if they can get away with that,” he said.

Juhapura, Ahmedabad’s Muslim ghetto and Chamanpura are also part of the author’s itinerary. “An eerie silence engulfed us. The entire gated community was desolate and lifeless…” he writes of Gulbarg Society in Chamanpura where 69 people, including women and children, were killed in 2002. “At the entrance, to my right, were sprawling two-storey homes with spacious balconies, porticos with round pillars and tiled flooring completely blanketed by dust, soot and scars of burnt human flesh and blood. Doors and windows had been ripped off, probably stolen by anti-socials. Fans and furniture in areas not destroyed by the fire were also missing. Spacious living rooms and bedrooms were bereft of furniture; burnt clothes and glass pieces lay scattered upon piles of other debris, mostly burnt wood.” He meets Rafiq Qasim Mansoori, who is wearing sunglasses. Asked whether he had been present during the massacre, Rafiq takes off his sunglasses to reveal a smashed right eye. “A stone hit me in the eye,” he said. “I lost 19 family members that day and that included my wife and infant son.”

In Godhra, Pradeep dwells on the town’s long history of communalism. Muslims there largely belong to the Ghanchi community and are poor and uneducated. During Partition, many Sindhis, belonging to the Bhaiband sect, migrated to the area from Karachi. They had experienced horrendous suffering at the hands of Muslims in 1947 and the memory festered. The first large-scale communal riot between Sindhis and Ghanchis took place in 1948. 3500 properties belonging to the Ghanchis were burnt down and many fled. Sindhis took over their lands. “Even at that time, arson was the top choice for rioters in this region,” Damodaran writes. Riots between the two communities have continued intermittently over the decades.

The author then interviews Maulana Iqbal Hussain Bokda, principal of Polan Bazar Urdu School. When the Maulana spoke about the social isolation and economic backwardness of Muslims, the author asks if he had ever regretted not emigrating to Pakistan. A disturbed Bokda points, through a window, at the tricolour flying high outside. “Since 2005, the flag has been hoisted every day at 7 am and is brought down at 5pm,” he said. “You tell me if you can find this anywhere in India. The tiranga is hoisted every single day! If one person cannot do it, someone else does. You know why? It is because we are Indians and we believe in this country.”

These are just some of the stories recounted in the book that marries travelogue to human interest reportage to come up with a snapshot of India today.

While the first section deals with different places in Gujarat, Part 2 focusses on Uttar Pradesh. The author’s first stop in the state is Jhansi where he visits the famous local fort, scene of Rani Lakshmibai’s daring leap, and marvels at its construction. The queen’s presence is ubiquitous and she appears everywhere on hoardings, government flex boards and in the names of colleges and other institutions in the town. Damodaran recounts that many in Jhansi asked him about his religious identity and were unnerved when he responded that he was an atheist. Invariably those who asked had “never moved out of their native towns and villages for generations”. “They had been fed stories about the grandeur and courage associated with their religion. Merely 75 years of imposed secularism are, perhaps, hardly sufficient to erase over 1000 years of religious devotion, as I could see first-hand,” he writes.

In Pala Pahadi village, the author hears a familiar nationwide lament: “Everything is rotting here; nothing has changed in the past 75 years. We have no roads, no drinking water, nor any form of sanitation. Where are the free toilets? Where are the schemes the government has announced? We have got nothing.” In Nandulan Khera, the people had converted most of the Swachh Bharat toilets into storerooms for hay and other non-essential items. Apparently, septic tanks had not been installed with the toilets. The few who had built their own septic tanks, could now no longer use them because lorries tasked with emptying them could not approach the village as there were no proper roads. So, the people went back to defecating in the fields.

The author travels to the village of Mankhi, where ex-BJP MLA Kuldeep Singh Sengar had raped a minor on June 4, 2017, causing national outrage. The girl’s father later died in police custody. Damodaran discovers that because of the danger to their lives, the family no longer lived in the village. 17 km away in Unnao, he meets the girl’s mother, Asha Singh, a Congress candidate for the UP Assembly elections. She bemoans the fact that men continued to rape women, especially of the lower castes, with impunity. All the publicity associated with her daughter’s case had changed nothing. The rape survivor stood next to her mother. “She was definitely smart; perhaps in a decade or so, she would be ready for the polls…” the author writes.

Chauri Chaura, Champaran, and Motihari too feature in this section.

The book’s third part begins in Punjab and focuses on the Ghadar movement, an early 20th century attempt by expatriate Indians to overturn British rule. Damodaran also visits Don Parewa (Nainital), Tamluk (Bengal), Tentuligumma (Odisha), Panchalankurichi and Idinthakarai (Tamil Nadu)

An eye-opening book, In Pursuit of Freedom is both a history lesson and a particularly sharp picture of contemporary India.

Shevlin Sebastian is a senior journalist. He is the author of The Stolen Necklace; A Small Crime in a Small Town.