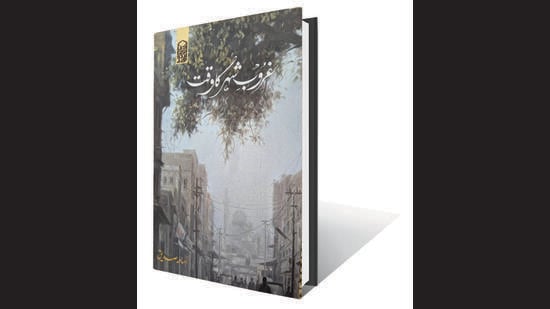

Review: Ghuroob-e Shehr Ka Waqt by Osama Siddique

A fierce love letter to a crumbling city, Pakistani author Osama Siddique’s first novel written in Urdu is both an ode to and a lament for Lahore

Like Kiran Nagarkar, and others before him, Pakistani author Osama Siddique has changed his literary language of expression midway through his career. But whereas Nagarkar went from writing in Marathi to English, Osama Siddique wrote his first three books in English. They include an acclaimed novel, Snuffing Out the Moon, published by Penguin India in 2016, and an award winning and truly path breaking research book called Pakistan’s Experience With Formal Law: An Alien Justice, before penning this outstanding ode and lament for Lahore in Urdu, the city that still shines with peculiar light in the hearts of millions of Indians. One of Urdu’s most respected living writers Mohammed Salim ur Rahman aptly summed it up when he said that “a city once resplendent with ideas and conviviality can be seen turning into a wreckage and Osama Siddique brings alive its decline with tremendous poise and poignancy.” Given how spates of animosity between India and Pakistan constantly endanger the transnational Urdu literary community, one is very grateful to Anjuman Taraqqi Urdu, Hind (the oldest autonomous body for the promotion of Urdu in the subcontinent and one which fittingly exists on both sides of the divide) for making this brilliant work by a Pakistani writer available to Indian audiences. It has received rave reviews from all quarters in Pakistan. Mustansar Husain Tarar, the great bilingual fiction writer whose Punjabi novel on Bhagat Singh has been hailed as perhaps the greatest account of one of our most celebrated icons, stated that Osama Siddique’s novel is proof that great prose can momentarily suspend our disbelief and habitual despair. Others have described it as the third greatest work of Urdu fiction in this century, after Shamsur Rahman Faruqi’s Kai Chand The Sar e Aasman and Mirza Ather Baig’s Ghulam Bagh. Still others have compared the novel to James Joyce’s Ulysses and to the works of the great novelist Qurrat ul Ain Hyder.

The novel is indeed a great ode to Lahore. It opens in the contemporary period with a man walking off the beaten path and into a cemetery, which then becomes a trope to explore the hidden paths that trail off into the past, into the future, into the universe, and into many different dimensions. The protagonist works in a celebrated lawyer’s office. Through them we are led to the shenanigans of this supposed public interest lawyer and the vagaries of the justice system. These take downs are savage and hilarious and go much further than anything one has read as satire in Hindi or Urdu. The Supreme Court judges who wish to end pollution in the city through an instant diktat, can only manage to come up with a most ridiculous solution. The entire judicial mechanism is lampooned in a splenetic manner. Similarly, the description of the protagonist’s youth and his days in the celebrated Government College Lahore, as well as the present condition of that institution are mercilessly derided. The caustic is here leavened by farce and by moments of blinding humour which leaves one in splits. It is not easy to at once capture so many different scales of humour – satire, farce, over the top lampooning, savage takedowns – in the same work but Siddique pulls it off with panache.

The takedowns are only one strand in a novel which digresses in several different directions. There are also wonderful vignettes about the doomed love affairs of the protagonist, his idyllic childhood in a big haveli in downtown Lahore, which are evoked with great figurative detail and sympathy for a refugee family attempting to reestablish its roots and find some dignity. These portions are evocative and lyrical. The person who stands out the most is the aunt Taiyyeba Khala, a poet, painter and scientist who suffers the moribund rituals of academic pretensions until she resigns her position. It reminds readers of that wonderful Tapan Sinha film, Ek Doctor Ki Maut in which the late Irrfan Khan made his debut as an actor. Her life and struggles are presented with tremendous sensitivity and her immensely poignant verse fills us at once with longing and desperation. Her character allows the novelist a rare foray, for a literary work this lyrical, into the world of astrophysics, of astronomy, of the big bang theory and all the unknowns that surround us, putting into question our lament for our pains, or our existence as well as all our knowledge.

Yet, that too is just one strand of the novel. There is also a mysterious prisoner, being shunted from camp to camp, which could be any of Pakistan’s heads of state who have all met the same fate at some point of their lives. A mysterious narrator, who lives on a tree, wreaks havoc on these camps and their ferocious soldiers and reminds us not just of the era of Jabr ul Haq, a wonderful pun on Zia ul Haq, the erstwhile dictator, but also on sundry other dictators that Pakistan has had the misfortune to endure. There are monkeys who dovetail into other creatures from other stories from other eras, the Jatakas, the Tilism e Hoshruba, the Betal Pacheesi and the Qissa e Chahar Darvesh, the famous tale of four dervishes which forms the prologue of the book.

The novel traverses eras but it is its close examination of the habitus of the city that it lovingly portrays and laments, which makes it at once a dystopian work as well as a fierce love letter to a city which seems to be crumbling; hence the title. The unique aspect about the novelist’s perspective is its multifocal lens. The city is examined through its educational institutions, through its waste and pollution, through the drying rivers, the asphyxiation of its fauna, but also via the dying of love, and of reading, and the loss of readers who can read not just the books but the other signs of decay, of craftsmanship and conduct, of comportment and calligraphy, of poetry and paterfamilias, of the loss of lament, as a matter of fact. This is a vision of a city that is rarely met in academia, where the poetry is missing, and equally rarely found in fiction, where the social sciences and environmental studies do not find enough traction. Now imagine if someone could bring to you the detailed map of a city’s demographic changes and its water tables, and its increasing carbon foot print, all done with great lyricism while your heart breaks for the protagonists’ doomed love affair. You would feel not just heart break but also the futility of that mere heart break when so much around you is being wrecked. That is how relentless and yet how controlled the novel’s narrative is. Here are some lines from one of the opening chapters of the novel, although I am afraid my translation does not do justice to the chiseled prose of the original —

“Where do I live? I am a resident of a broken city in a turbulent era.

Where the city’s once fabled sweet life giving water is now disappearing deep inside the bowels of the earth. And where the city’s once famed refreshing breeze has now become a story from the past.

Where the wheels of justice grind so harshly, so harshly that one is reminded daily of the inferno and one forgets even the spelling of justice.

The product of a moribund, fungus ridden, ruined educational system.

The member of heartless society where love, affection, kindness have lost valence.

The resident of such a city where it is now impossible to love, and where it is becoming even more impossible to love the city. “

Yet that is not all that it is. It is teeming with ideas about people, about fiction, about history, about the universe, which seem to reflect in the protagonist’s vision about his own city. The novelist takes us on detours with Fernando Pessoa, Ismael Kadare, Marcel Proust, Italo Calvino and Jose Saramago, into their cities, into their loves and laments and how it dovetails with the novel’s time and place. It also breaks new ground in its form which is not a linear narrative nor a simple building up of layers. The layers are labyrinthine, like the city described, and they remind us as much of the Thousand and One Nights as they do of Jorge Luis Borges, which is fitting given how much Borges admired the former. It is remarkable to fit in so much pathos, with so much humour, so much longing with such remembrance, such heartbreak with such ridicule, and such a teeming world of characters, both human and non human. The gaze of the novelist is all encompassing, but also equally relentless in its determination to expose the underbelly. It is like Intizar Husain was writing of the mysterious forces governing our modern existential lives but could also at the same time examine the social roots of that evil. Society, economy, judiciary, professions, education, nothing is left out of that gaze. One of the most chilling characters is a young street urchin who targets dogs for sport in a chapter that is almost unreadable in its sharpness and in the violence that it builds up so unbearably.

This is a novel about beauty and form, about love and loss, but it is not just about Lahore, but also about many other cities of the subcontinent. It is a bitter lament for what we are doing in the name of progress and development and a grim reminder that while we may have been less well provided for in the past, we had many other riches which we have squandered. Consequently, we are now rudderless and face an unhinged ruling elite and a clueless mass of residents whose everyday survival leaves no room for the very things that make life worth living. Few Urdu novels have been so universal, not just in their concerns and depictions, but also in their structure, their prose, their inspiration, and their relevance. It is an astonishing debut.

Osama Siddique’s novel Ghuroob–e Shehr Ka Waqt will be formally launched in India at the India International Centre, Delhi, on 13th July.