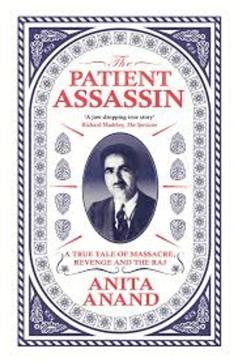

Book Review: The Patient Assassin by Anita Anand

Anita Anand’s biography of the man who assassinated General Michael O’Dwyer, the former lieutenant governor of Punjab to avenge the massacre at Jallianwala Bagh, vividly describes imperialist impulses and the nationalist movement in Punjab

In 1940, an Indian man, despite being on the radar of British intelligence agencies, walked into a public meeting in Westminster, the high-security government area of London, and assassinated a former lieutenant governor of Punjab, in a room full of important officers and military men. This was retribution for the massacre at Jallianwala Bagh.

It is widely believed, Udham Singh had sworn revenge two decades before at the blood-soaked garden in Amritsar in 1919. The massacre, which killed about 1,000 men, women and children, according to Indian estimates, had occurred largely due to Michael O’Dwyer’s policies and attitude towards Indians during his incumbency in Punjab. Singh’s other target, Reginald Dyer, the general who had ordered his men to open fire at the gathering of 15-20,000 people in the public garden, had long died of illness — Dyer’s family believed he died of a broken heart.

Singh was executed as “the most hated man in Britain” but despite attempts to contain them, the British could not hide his motivations for murder. The Jallianwala Bagh massacre was once again in public memory. Nazis used it as anti-British propaganda, Joseph Goebbels encouraged a revolt in India, “The assassination was a vendetta and a justified one at that.” And although the Congress leadership condemned his actions, Singh became a shaheed, one of the great martyrs, in India.

The real Udham Singh, as it turns out in Anita Anand’s gripping biography The Patient Assassin: A True Tale of Massacre, Revenge and the Raj, is perhaps Punjabi nationalism’s greatest anti hero. It’s a rags-to-riches story of a flamboyant man who moved around the world juggling multiple identities, dodging police and intelligence agencies everywhere. It evokes the quiet suspense of a masterful spy novel. Its film rights were sold before it was published.

Anand, a journalist with the BBC in London, pieced together Singh’s mysterious life using research and records from around the world, including top-secret British government documents. She tells this story through an assortment of characters, quickly sketching out even minor actors in the narrative, giving readers glimpses into multiple points of view.

The first section of the book is a biography of Jallianwala Bagh and its villains. Anand describes the ground, covered with translucent paper wrappings of Amritsari street food, where many families including children had come together just to meet and eat. Anand describes eyewitness accounts from both sides after the shooting began, “wherever there was hope, there was death” she warns as she lists the names and details of the victims and survivors.

Anand is particularly vested in this because her grandfather was at the grounds on the day of the massacre and carried survivor’s guilt for the rest of his life. She was brought up fearing the names of Dyer and O’Dwyer, and could only write objectively when she thought of them by their first names. She writes about their lives and motivations in great detail.

Dyer, who grew up a sensitive boy in Kasauli where his father grew hops for beer, carried a genuine affection for India, which had been his family’s home for three generations. “He was utterly at ease with the ‘natives’.” The camaraderie between Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs — walking hand-in-hand chanting “Hindu-Mussalman ki jai” on Ram Naumi in Amritsar — had left him bristling. He was also irked by the “insolence” of Amritsar where “the natives here no longer stopped and salaamed British superiors.” He was brazen after the massacre, but was eventually forced to confront his actions and spent the rest of his life muddled by grief, guilt and confusion.

O’Dwyer, on the other hand, remained unrepentant. Anand writes about the terror he unleashed in Punjab after the massacre. He ordered an RAF airplane to fire at a group of peasants on their way back from work; women and children were cut to pieces by automatic fire; homes were fired at, people chased out, schoolboys were whipped. He is lesser known perhaps because Punjabis conflated Dyer and O’Dwyer’s similar sounding names and merged them into one composite villain.

The two white men in turn saw all of Amritsar as one complicit villain. “Amritsar,” Anand writes, “was filled with innocent civilians, yet Sir Michael and Dyer regarded them as complicit. They were either rebels or rebel sympathisers. It made the idea of collective punishment so much easier to peddle if lawyers and law breakers were painted with the same brush.”

Udham Singh comes to the fore only a third into the book. He was raised in an orphanage, served in Mesopotamia during the First World War, went to Africa practically as bonded labour to work in the construction of the Ugandan railways, during which some 2,500 men died. But Singh disappeared mid-contract possibly after coming in contact with the militant nationalist Ghadar Party which, crushed in Punjab, had resurfaced in East Africa.

And so began Singh’s globetrotting adventures.

He returned to India with new papers, a lot of money and ideas of the revolution to spread in rural Punjab where he talked about being an important man “destined for much bigger things.” Nobody believed him.

He accompanied a prospective engineering student, a perfect cover for a barely literate man to go to London where, through a gurdwara network, he learnt about entering America via Mexico. In California, Singh smuggled other Indians across the border for the Ghadars. He married a Mexican American woman, they moved often, eventually ending up in New York. He returned to Amritsar using a Puerto Rican identity, and was imprisoned when his contraband was discovered at the local brothel. After serving his sentence, he went to London where he rented several accommodations, had a bike and a car, and showed up to Sikh get-togethers with goodies and white girlfriends. He talked about his thirst for revenge often and openly — and made no efforts to lay low, even when he was begun to be followed by plainclothes cops. He loved basking in attention. He was an extra, an Indian among several blackface white extras, in Alexander Korda’s 1937 adventure film Elephant Boy, an adaptation of a Kipling story.

The Ghadars sent him to Europe often. His trips to Russia could mean he was an Indian Bolshevik soldier. Or maybe he worked with German agents in Berlin. He got caught several times, but somehow managed to get away— until he shot O’Dwyer in the heart. And that too, was followed by drama.

The man charged with O’Dwyer’s murder was called Mohammed Singh Azad — Udham Singh’s last alias, a secular and free one. At the public meeting in Westminster, he had aimed at a few others including the secretary of state for India — but his malfunctioning gun was too loose for the smaller bullets inside them. He insisted it was meant to be an act of protest, he didn’t mean to kill anybody. He became “the most hated man in Britain” — where O’Dwyer had been deeply loved for his loyalty to the Empire — even before his real identity was traced. The Nazis immediately appropriated ‘Azad’ and despite attempts to contain them, the British could not hide his motivations for murder. The Jallianwala Bagh massacre was once again in public memory by the time the British realised that Azad was in fact Udham Singh, a Ghadar and a communist, who had slipped through the watch of all of their security agencies several times. The press was muted and the British government insisted Singh had no connection with any foreign powers or with the Amritsar massacre. All of this was happening while the world was on the brink of the Second World War. Some of the MI5 files on Singh are still sealed and buried.

In jail, Singh almost managed to get a blade smuggled in. He wrote in a letter, “I fancy that I shall put up a bit of show as I said in America, but I am not afraid to die.” In court, he called out for Inquilab.

Read more: Pop princess, rockstar suffragette: How Sophia Duleep Singh fought for voting rights in UK

This is a gripping and engaging book. It vividly describes the nationalist movement in Punjab as well as imperialist impulses. It’s a testimony to the dangers of unchecked power and what it does to people — making it relevant and timely in 2019. Like Anand’s Sophia: Princess, Suffragette, Revolutionary (2015), a biography of Sophia Duleep Singh, the activist granddaughter of the Sikh ruler Ranjit Singh, The Patient Assassin does more than it sets out to.

It opens with Singh’s mishandled execution. From the onset, readers assume they know where the story is going, especially since parts of it are so familiar. Yet, every chapter is unexpected and suspenseful. And ultimately the thrill is in trying to ascertain if Udham Singh was an excellent spy trying to be inconspicuous by his exuberance — or just manic.

Saudamini Jain is an independent journalist. She lives in Delhi.