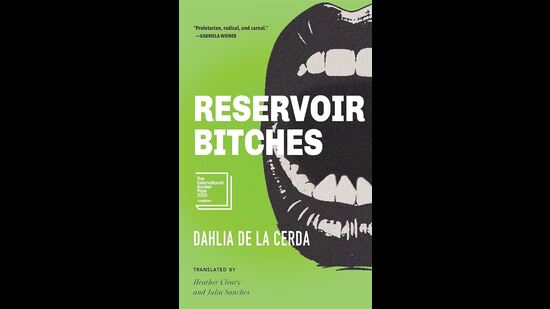

Review: Reservoir Bitches by Dahlia de la Cerda

It is a set of linked narratives of 13 women in Mexico that looks at the common villains of misogyny and patriarchy.

‘Disposable women. Decapitated women. Strangled women. Dismembered women, Raped Women.’ If Stephen Graham’s Netflix show Adolescence were to be told from the point of view of girls and women like Katie, who die every day at the hands of boys and men, Dahlia de la Cerda’s Reservoir Bitches would be where you’d hear their voices. Longlisted for the 2025 International Booker Prize, this book — translated from the Spanish by Heather Cleary and Julia Sanches — is a set of linked stories of 13 women in Mexico.

The collection begins with Parsley and Coca-Cola where a young woman discovers she is pregnant and is on the move to abort the child. At the outset, readers are made aware that these are not stories involving dramatic emotional roller coasters or about intemperance. The woman here is not the one in Annie Ernaux’s Happening (2001), who trudged through the tragedy of abortion and spiralled into an emotional vortex. Rather she admits, ‘My abortion lacked drama… This was less a tragedy than a bad period plus the flu.’ This tone of nonchalance is spread across all the stories and works excellently as a literary motif that suggests the everydayness of the violence to which the female body is subjected. Additionally, there is an admixture of humour in the exploration of the varying subjectivities of women controlled by the common villains of misogyny and patriarchy.

Reservoir Bitches represents women from different walks of life and zeroes in on the rationale behind the way they react. For instance, Yuliana, the daughter of an important and rich man, dresses expensively and has bodyguards. Her life’s motive had been to “be a superhot housewife and devoted mother.” But when her best friend is found dead, something flips in Yuliana. She becomes aware of the power that she has always had but held as other to her feminine persona.

The portrait of a young transwoman in Sequins particularly stands out. The author uncovers the layers to the character who is born a boy, dresses up as a girl, identifies with the female parts while performing, and is eventually thrown out of home. The most enduring scene in the story has the mother pleading with the child to “be a faggot if you want, just don’t dress like that, Jules, for the love of God.” This line brings out larger concerns within the LGBTIQA+ community itself where being sexually divergent is tolerated but the act of changing the body through the opposite gender’s paraphernalia is still viewed as indecorous. The invocation of a number of dead queer activists from Latin America and Mexico is a heartbreaking and fitting tribute to the queer movement and to the many transgender individuals who have been murdered for just being themselves.

La China and God Didn’t Come Through are fine studies of villainy. In the first, La China is a woman who works for drug lords; shooting and violence are a part of her job. In the other story, a young girl raised in poverty goes for days without eating until she realizes something about herself: “I’ve been surrounded by poverty and hunger my whole life. I’ve lived with violence and wanted to join a gang… to be a part of something, to have family and some support.” These are women battling the reckless tumble of life. Fans of Fernanda Melchor’s Paradis (2021), translated from the Spanish by Sophie Hughes, would be enticed by the characters in la Cerda’s collection.

Short pieces that flow seamlessly, these stories use language that pierces readers’ minds and remain wedged there. This works especially well when the protagonist is young and has a hint of restiveness. However, after a point, the voices begin to sound the same. Without names and differentiating features, it would be difficult to distinguish one woman character from the next. This prevents the collection from offering a proper understanding of divergent women.

Apart from having voices that are indistinct from one another, these stories also have a teleological problem. They appear to have been written solely to record the violence women face in Mexico. After a point, they read like reportage. This is especially true of the last story, La Huesera. The reader begins to miss a book like Claudia Piñeiro’s Elena Knows (2021). Written in the context of increasing violence against women and the issue of abortion in Argentina and other Latin American countries and translated from the Spanish by Frances Riddle, Pineiro’s account of a woman navigating life through disability, abortion and the search for freedom, is heartbreaking. However, not for a second does the reader feel as though the author is attempting to ham-handedly manipulate them.

Still, the simultaneously engaging and disorienting stories in Reservoir Bitches present a vivid picture of misogyny.

Rahul Singh is a PhD candidate in Sociology at Presidency University, Kolkata. He writes about books at (@rahulzsing) X and (@fook_bood) Instagram.

All Access.

One Subscription.

Get 360° coverage—from daily headlines

to 100 year archives.

HT App & Website