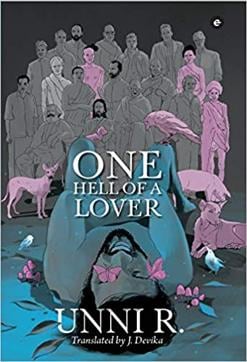

Review: One Hell of a Lover by Unni R

Unni R’s stories deal with a perverse masculinity

Unni R’s One Hell of a Lover left me rather disturbed, and I say that pejoratively. A majority of the stories deal with a perverse masculinity or depict men as wastrels. Men air their grotesque sexual fantasies, women are not perceived beyond their bodies, lust clearly overpowers love, and the interiority of the characters remains unexplored. Characters in fiction ought to be perceived beyond their immediate actions but there is very little in these stories to even aid that comprehension or insight into characters.

In a few other stories, the male central characters are seen plotting the death of their employer or drinking with a group of friends, which soon takes a violent turn, or collecting obituaries of people from far and wide while sitting naked in their library, and wanting to engage in sex only in the bath tub. Idiosyncrasies and character quirks abound in Unni’s stories but idiosyncratic character traits alone do not contribute to ingenuity in fiction. It might resonate on celluloid; I say this with the awareness that the author is also a well-known film writer. But literature and cinema are not the same though they overlap in some ways and borrow from each other. These are different media with distinct demands. After reading the stories, I was left wondering why these characters behave the way they do. To say that’s unexplainable or citing the social milieu as a possible reason for performance of such masculinity is only half the answer. And why can’t a relatively smaller place like the Kudamalloor village in Kerala’s Kottayam district (Unni’s home village and the setting of many of his stories) be imagined beyond characteristic tropes of tea stalls, alcoholism, blue films, Communist pacha etc?

Then there are stories where a Radha wants to settle the score with Rameshan who groped her in a crowded bus, Kurudi Ummachi and Zulfat travel the world through travelogues and quick trips to local spots imagining the Meenachil river as the Thames, Raziya wants to call the azaan. There are some heart-warming moments in each but the representation seems tokenistic. I hope the author has no delusions of confusing these acts as empowering. In Leela, the central character, Kuttiyappan, makes Elyamma chichi, who cooks for him, have a terrible fall. When his friend Pillecha asks him to explain his behaviour, Kuttiyappan nonchalantly says it would be so boring if she gave him black tea in exactly the same way every day. So he fixed a ladder and asked her to climb up to his window to give him tea. She is under excellent treatment now and will continue to receive his benevolence. How does the reader even fathom this? As ingenious storytelling, crude masculinity or plain deviance? It is easy to like the women in his stories and despise the men but that is too simplistic. Unni R’s characters are ordinary men and women folk but his idea of the ordinary or the representation of it is trite and uninspiring.

Read more: Review: Reel India by Namrata Joshi

While the author might be well intentioned in documenting a kind of ugly and insensitive masculine behaviour and everything that is wrong with it, I couldn’t help wondering if this is an attempt to normalise it. In the translator’s note, J Devika writes, “Unni R represents a new generation of male short story writers who have, perhaps for the very first time in the history of Malayalam literature, chosen to turn a searing eye on what is too often deemed as the very grounds of literary creativity in Malayalam: the Malayali macho masculine”. While I get the point Devika is trying to make, I still find it difficult to look beyond the deep-seated feudalism and the hideous male gaze that dominates the narrative. We can begin to discourse about fiction or other literary aspects when we get past that stage.

Kunal Ray teaches literary & cultural studies at FLAME University, Pune