Review: Once Upon A Prime Time: My Journey on Indian Television by Ananth Mahadevan

Actor and director Ananth Mahadevan looks at the phenomenal growth and the eventual qualitative fall of the television industry through his own life’s journey

Once Upon a Prime Time by actor, writer and director Ananth Mahadevan is a bomb of nostalgia. Brimming with details of the golden age of Indian television, this is as much a treasure trove for those who grew up in the 1980s and 1990s, when watching TV was the only means of recreation for families, as for those whose interest in those years is purely academic.

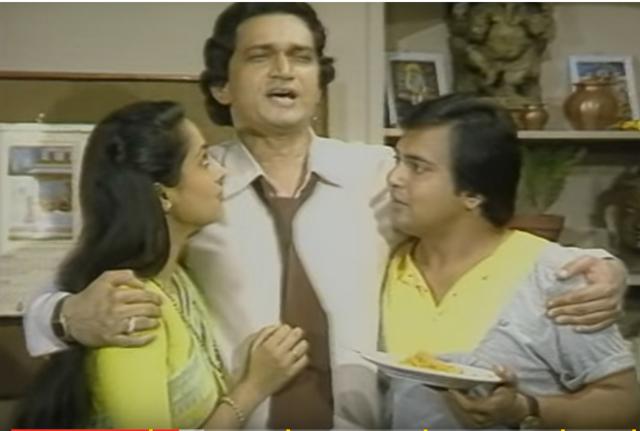

It will bring back memories of the rib-tickling Shafi Inamdar-Satish Shah-Swaroop Sampat-starrer Yeh Jo Hai Zindagi, the success of which, despite several attempts over the next four decades, has never been replicated. It will also bring back memories of good old Doordarshan, of Krishi Darshan, of the constant disruptions (“Rukaawat ke liye khed hai”) or the blank screen reverberating with static waves. And scores of other shows such as Hum Log, Buniyaad, Khandaan, which are firmly etched in the collective memory of Generation X.

Mahadevan looks at the phenomenal growth and the eventual qualitative fall of the television industry through his own life’s journey. In the summer of 1964, as a child, he marvelled at the sounds emanating from a radio set owned by his uncle. By the time television arrived he was fresh out of college and waiting to live his dream of becoming an actor. The obsessive pursuit of this dream was anything but easy.

Mahadevan documents the twin journeys, of television and himself, with clinical precision, letting in the readers on the industry’s dirty secrets, and magnifying some of the brutal blows he was dealt to indicate how deceitful that world was. This dispassionate account of an era is peppered with anecdotes that only an insider could have been privy to – snippets of what transpired in the corridors of Prasar Bharti and what it took to get past the red tape, or the ugly truths of the flashy new private channels that demolished Doordarshan.

The first broadcast on Doordarshan, still a part of All India Radio then, was in September 1959, when officials, “in the absence of air-conditioning machinery, were cooling with ice slabs, a closed-circuit television, that the Philips company from Holland had chosen to abandon”. The game changed in the early 1980s when the secretary for Information and Broadcasting, SS Gill, toured Mexico and wanted to emulate the success of the soap operas there. He invited “middle-of-the-road filmmakers” such as Basu Chatterjee, Gulzar, Sai Paranjpye, and Kundan Shah to make shows.

But this was the 1980s and who wanted to do television? When no one paid heed, a determined Gill stalked Kundan Shah who was in Delhi to receive the national film award for his cult film Jaane Bhi Do Yaaron (1984).

Shah wrested the prime time slot with Yeh Jo Hai Zindagi. The anecdotes that Mahadevan squeezes in makes this book endearing: the show became so popular that the team dictated to the ministry what slot they wanted; Satish Shah was to play the part of the husband, but failed the looks test; the uniqueness of his character(s) – he played a different role in every episode –stole the show.

Before Yeh Joh Hai Zindagi, it was Hum Log that kept the great Indian family glued to their TV sets. The experimentation at DD continued with a variety of shows slotted for weekday prime time, till Ramayan was telecast, or as Mahadevan writes, till the “mytho pill” was served and “Sunday mornings assumed the mantle of a pilgrimage”.

Mahabharat took over the viewership of Ramayan, but not before a war in court. That BR Chopra hired celebrated Urdu poet and writer Rahi Masoom Raza to write the script for Mahabharat didn’t go down well with the officials at Doordarshan. “How could a Muslim write a Hindu epic?”

Mahadevan recalls the channel demanded a narration of the scripts and the Chopras grudgingly gave in, mentally prepared to quit the show if the scripts weren’t approved. “As Rahi sahab read out the first four episodes, SS Gill’s eyes virtually popped out. The writing took them by surprise. The green light was unanimous.”

The Mahabharat saga did not end here. When the show was slotted on air, the Vishwa Hindu Parishad sent a notice to the Chopras. However, when the Sangh saw the first episode, they sent a letter of apology. How times have changed!

By the early 1990s, there was a flurry of private channels and the most creative people had tired of chasing the babus at Doordarshan. Around the same time, Balaji Films made its debut. It shot to fame with the comedy show Hum Paanch (1995) and went on to do the saas-bahu serials, topping the TRP charts and setting the ball rolling on the “idiot box”.

The new millennium opened with reality shows such as Big Boss and Kaun Banega Crorepati – which changed television viewing. Popular shows were wrapped up unceremoniously and everyone made way for KBC. Several news channels, too, mushroomed around the same time, killing the evening newspaper and giving the “soap scriptwriters a run for their money”. The ground has become murkier since.

Mahadevan’s pinnacle of fame as an actor was his role as Pandit Purnaiya in The Sword of Tipu Sultan. He does a good job of taking the reader on this four-decade bumpy ride and has a way with words. However, sometimes his observations are a drag and one wishes that the book didn’t run into so many pages. The foreword by Hema Malini, whose Noopur Mahadevan directed, doesn’t gel with the tone of the book and is as much a put off as is all ghost writing.

Lamat R Hasan is an independent journalist. She lives in Delhi.