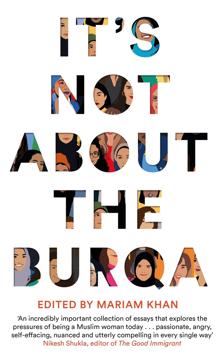

Review: It’s Not About the Burqua edited by Mariam Khan

A book of essays by Muslim women that takes on Islamophobia, the white feminist perspective, and other issues to do with the Muslim woman’s lived experience today

The burqua or hijab or veil has been a subject of controversy both in the West and in the rest of the world since 9/11, which marked the rise of Islamophobia. It soon became apparent that there was widespread prejudice and great ignorance about Muslim lives, customs and practices. Former British prime minister David Cameron did not think he was stereotyping when he described Muslim women as traditionally submissive. Clearly, he had not heard of Zeenat Aman, Parveen Babi, Begum Akhtar or Sania Mirza. The invocation of this stereotype troubled Mariam Khan and inspired her to present a wider perspective by sharing the lives, experiences and views of 14 accomplished women in this volume.

In the context in which the global debate has emerged, the word ‘burqa’ has become over-politicised and is seen as synonymous with a Muslim woman’s identity. Khan writes, “By engaging with this narrative I hope to dismantle it from within. Muslim women are more than burqas, more than hijabs, and more than society has allowed us to be until now.” She urges readers interested in this question to listen to the Muslim women and their perspectives. Like women of other religions and cultures, Muslim women too have their own ways of negotiating their lives, asserting themselves, and taking decisions, personal and professional in the face of many domestic and societal challenges.

Mona Eltahawy, noted Egyptian feminist, author of Headescarves and Hymens: Why the Middle East Needs a Sexual Revolution, calls for a new kind of revolution to grapple with stereotypes. She says that, as a woman of colour, a Muslim, and a feminist, she found the observations made by black American civil rights activist, Toni Cade Bambara, very inspiring. “As a cultural worker who belongs to an oppressed people, my job is to make revolution irresistible,” Bambara said in an interview. What does this idea of irresistible revolution look like? She explains that revolution is “too loud”. “It defies, disobeys, and disrupts patriarchy. It swears too much -- and tells racists and Islamophobes to mind their businesses.” She feels deeply uncomfortable with the idea of leaving Muslim women’s issues to the community because community is synonymous with men, and is identical to the word, “culture”. In other words, community or culture ultimately implies nothing but men. So she asks: “Who determined that it was culture and who speaks for the community? Men and men. That is the simple answer.” She says that as a Muslim woman and as a member of a minority, she is caught in the midst of the violence of racism and bigotry in the West. Similar ideas come up in other essays in the volume.

Nafisa Bakkar is insightful in the chapter entitled On the Representation of Muslims. Muslims are the second largest religious community in the world today after Christians and live nearly in all the countries and continents of the world. This makes it a diverse community. Not surprisingly, their representations are also diverse. “Being Muslim is steeped in my faith and practice of Islam; to someone else it may be found in their cultural background, or it may be a political statement, or just something that came to light twice a year at the Eid celebrations,” she says, adding that the attempt to paint Muslims with one broad brush stroke is deeply misleading.

Some of the chapter titles indicate the diversity of the content: There is Hijabi (R)evolution by Afshan D’Souza-Lodhi, Gender Denied: Islam, Sex, and Struggle by Salma El Wardany, How Not to Get Married (or Why an unregistered nikha is no protection for a woman) by Aina Khan, and Eight Notifications by Salma Haiddraini. Together these essays cover a wide range of themes and include almost all the issues women consider vital to their dignity and freedom.

The editor herself has an essay with a provocative title: Feminism Needs to Die;Muslim women in the West. Mariam Khan argues that women are often encouraged to look at their culture, ideas of liberation or equality purely from the white feminist perspective. This is problematic as it disapproves of the hijab, the burqua, of modest culture and other key elements of a Muslim woman’s identity. Some feminists (not all of them white) might argue that the so-called culture-centric Muslim woman identity is a creation of Muslim men, that there is an umbelical cord between the two that needs to be ruptured, and that whether this is owing to white feminist ideology or to any other forms of feminism is immaterial. Clearly, universal feminism doesn’t exist and the question of how to reconcile with diverse forms of feminism is a topic that needs to be studied.

I am Not Just a Black Muslim Woman by Raifa Rafiq raises precisely this question and presents content for a new narrative on diverse versions of feminism. “I am a black Muslim woman. What can such a statement tell me about me? Other than that my home is the central intersection in a Venn diagram of oppression,” she says.

The writing in this volume is based on lived experience, and the authors use their family histories and cultural interactions mainly in the West, often reacting sharply to Western constructs. All in all, this is a much-needed narrative to make sense of the Muslim woman’s voice raised against Islamophobia and its distorted constructs, which are often presented as the only truth of our time.

Shaikh Mujibur Rehman teaches at Jamia Millia Central University, New Delhi. He is the author of the upcoming book, Explaining the Muslim Mind.