Review: Independence by Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni

For close to three decades Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni has been prolifically churning out best sellers that examine the South Asian diaspora experience, immigration and cultural conflicts, reprise mythological and historical tales from a female perspective and experience, and interrogate patriarchy and celebrate feminism

For close to three decades Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni has been prolifically churning out best sellers that examine the South Asian diaspora experience, immigration and cultural conflicts, reprise mythological and historical tales from a female perspective and experience, and interrogate patriarchy and celebrate feminism. Years ago, her Palace of Illusions followed by One Amazing Thing established her as an engaging story-teller. Oleander Girl some years later, felt tepid in comparison. The recent two successes bear witness to her celebrity status, The Forest of Enchantments, a retelling of the Ramayana from Sita’s perspective and The Last Queen, based on the life of Maharani Jind Kaur of Punjab.

Independence, her new novel is a simmering cauldron bringing to a boil, questions of sisterhood, nationhood, love, betrayal, sacrifice and ambition. It is the story of three sisters set against the turbulent backdrop of Partition, precisely from August 1946 till February 1948, with an epilogue from 1954. The final exultant moments of India’s fight for Independence and the violent stories of Partition – two sides of the same coin – make for the grim mis-en-scène for the family saga.

The story is narrated in a simplistic linear fashion, and unfolds through the alternating eyes of the sisters. In the opening pages, the characters are introduced in the idyllic setting of Ranipur, “a village bordered by green-gold rice fields” on the banks of Sarasi river, “a slender silver chain” with breeze “smelling of sweet water-rushes” in an as-yet-undivided Bengal where a young girl, Priya and zamindar Somnath Chowdhury, her father’s best friend, sit playing chess. It is August 1946 and “everything is about to change”; armed with foreknowledge the reader braces for tumultuous times ahead. Priya is the feisty youngest daughter of Nabakumar Ganguly and Bina, sketched as a girl with a mind of her own who dreams of being a doctor like her father, is his second daughter. The eldest, Deepa is the “beauty of the village – fair skin, rose-petal lips, soulful eyes, hair like a waterfall”. Jamini, the third one, is drawn a little flawed in comparison to her sisters. Life for the Ganguly sisters is tough but largely placid. “Money is always short in the Ganguly household.” They manage to make ends meet thanks to the Kantha-embellished quilts made by their mother and their father’s medical practice that is “hobbled by a bad habit”, his overt magnanimity with poor and needy patients.

READ MORE: Interview: Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni, author, Independence

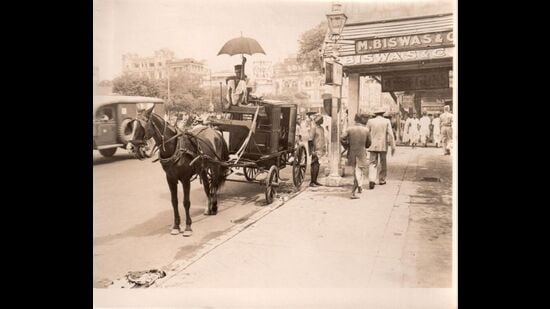

The Gangulys lives are upended on Direct Action Day, or the 1946 Calcutta Killings, on a rare family trip to Calcutta. Personal tragedy strikes as violence erupts all around them. They witness unprecedented communal hatred in a Calcutta where just a day before, at the popular Nahoum’s bakery, Jamini has observed, Christians, Muslims, Jews and Hindus, distinguishable from their clothes,“all rub elbows and think nothing of it”. “The photographs are the worst, streets filled with bodies, charred skeletons of buildings, slums where hundreds died in fires.” In a similar vein, Divakaruni chronicles the dastardly massacres, rapes and arson in Noakhali that took place in November 1946, and the aftermath, which eventually impacts the village of Ranipur. It is in the historical accounts and the anecdotes that weave the fictional stories with true-life events that the storytelling is more impactful.

An impassioned Nabakumar Ganguly and his close friend Dr Abdullah, speak in unison of their participation as impressionable youth in Gandhiji’s Salt March, of witnessing first-hand the zeal of Sarojini Naidu and Matangini Hazra. In a manner that is stylistically reminiscent of Forrest Gump’s encounters with real-life personalities, Deepa sings Rabindra Sangeet at the behest of a young Mujibur Rahman, at a dinner in Dacca hosted by her husband Raza. A kindly Sarojini Naidu makes a cameo appearance in Priya’s vastly altered existence towards the end. The writer also doffs a hat to Anandibai Joshi, the first woman doctor to graduate in western medicine from the Woman’s College of Medicine at Pennsylvania; Priya is encouraged by zamindar Chowdhury, her father’s friend, to seek admission there when she is rejected by the Calcutta Medical College for her gender.

The narrative is also embellished with snippets of Nazrul’s songs and Tagore’s poetry, a favourite of the writer. “Who is it that dares ask, ‘The drowning ones — are they Hindu or Muslim?’ Say instead, they are humans, they are the children of my motherland.”

The heft of the narrative in ‘Independence’ lies in the emotional interplay between the siblings, with their distinct personas: “Deepa scintillates in her confident beauty; Jamini is pale with virtue and suppressed longing; Priya glows, passionate with purpose.” Where there is intense love, there are also animosities. A significant sub-plot, a triangle fraught with passion, jealousy and sacrifice, plays out between Priya, Amit, the zamindar’s son and her childhood friend, and Jamini. It culminates in a feverish paced denouement. The dynamics of sisterhood has been one of Divakaruni’s favoured tropes. Her Sister of My Heart (2000), and its sequel The Vine of Desire deal with the complexities of the deep bond between two cousins.

Independence is dramatic and there is a cinematic feel to its storyline. While the plot carries the momentum of a page-turner, the narration is stymied by trite prose. “Under a fragrant kadam tree, they exchange their first kiss. They talk and talk, storing up love words for the dry weeks ahead.” One wonders if the choice of idiom, often demodé, is a deliberate one to capture the essence of a different era. Certain episodes have facileness, and one wishes the writer had gone beyond the skin-deep, especially for a saga of this nature. It brings to mind the parallel that has been purportedly drawn between Independence and the Louisa May Alcott classic Little Women, which is richer in texture. Like in the latter, Divakaruni’s girls must show fortitude and sacrifice, withstand war and betrayal, transcend societal limits and shine through it all. “The sisters listen, mesmerized by the woman’s breathy voice. They dream of impractical things. Travel, adventure, breaking boundaries. Is it possible, if one goes beyond the known world, to return?”

Sonali Mujumdar is an independent journalist. She lives in Mumbai

The views expressed are personal

All Access.

One Subscription.

Get 360° coverage—from daily headlines

to 100 year archives.

HT App & Website