Review: How I Became a Tree by Sumana Roy

A rare meditation on the plant world that meanders through history, religious philosophy, botanical research, literature, cinema, folklore and mythology

In her 1985 book of essays, The Solace of Open Spaces, film-maker Gretel Ehrlich writes of the time she spent in the rocky landscape of Wyoming, US, tending sheep, battling the cold, and coming to terms with the death of the man she loved.

Mussorie-based writer Stephen Alter undertook a series of treks in the Himalayas after recovering from a brutal assault by burglars who had broken into the family home and left him and his wife for dead. In his 2015 memoir, Becoming a Mountain, he writes of the emotional healing he experienced when he spent time in the mountains .

Suffering, it seems, is what often draws people to the natural world. We all may appreciate its beauty, but its therapeutic powers are sought most actively by the world-weary – fatigued, perhaps, by the inscrutability of life, the limitations of language and other people – or those living through grief so intense that it can only be shared with the mountains, and the rivers, and the trees, and the birds.

At times, the quest is also aspirational – for a simpler, non-violent way of life. As Polish poet-novelist Czeslaw Milosz writes in his 1978 poem ‘Notes’, “Not that I want to be a god or a hero. Just to change into a tree, grow for ages, not hurt anyone.”

Sumana Roy’s memoir-cum-ode to trees is an exploration of this very desire. She wants to, quite simply, become a tree. It started, she writes, with a desire to slow down and enjoy the freedoms trees have – of not being slaves to time, or being forced to put up with social pretensions. The contrast between the intolerance and ruthless ambition of humans and the indiscriminate generosity and altruism of trees also pushed her towards them.

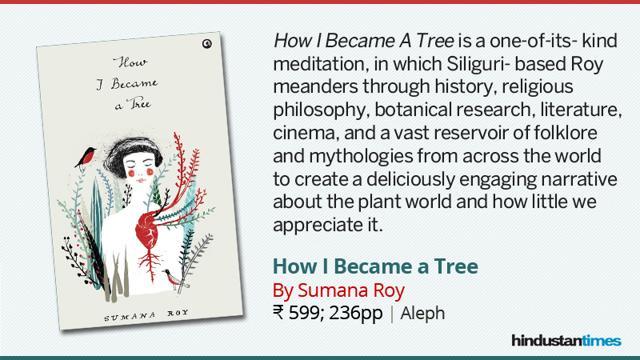

How I Became A Tree is a one-of-its-kind meditation, in which Siliguri-based Roy meanders through history, religious philosophy, botanical research, literature, cinema, and a vast reservoir of folklore and mythologies from across the world to create a deliciously engaging narrative about the plant world and how little we appreciate it.

In her attempt to explain (to herself and to the reader) her rather odd desire, Roy seeks out kindred spirits across time. There’s a delightful chapter on the gardens of Tagore and his love for plants as expressed in his stories, poetry and personal letters.

In another, she looks at botanist Jagdish Chandra Bose’s experiments with and efforts to understand the secrets of plants whom he loved like his children. These, along with stories of other such nature lovers like photographer Beth Moon (who travelled across the planet for 14 years, photographing the world’s oldest trees), writer DH Lawrence, author Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay, and artist Nandalal Bose (who had ‘started to see his Siva in trees’), are the most enjoyable and informative portions of the book.

There are also mentions of little-known heroes, like Bapi Green Taxi (a Calcutta taxi driver who has installed potted plants inside his vehicle and requests every passenger to go home and plant a tree), and more famous ones – Jadav Payeng aka The Forest Man of India, who singlehandedly planted a forest along the river Brahmaputra near Jorhat in Assam.

Read more: Excerpt: How I Became A Tree

Though Roy’s musings often provide unique insights and alternative perspectives about the nature of the world – both natural and human, at times they get a bit much (Like when she contemplates why do we not have statues of trees, only to contradict herself later in the book with “a tree statue would be a piece of tautology”). Also, if the author had shared a bit more about herself in the book, it would be easier to connect to or feel invested in her anecdotes about her childhood games and art classes.

This is a book strictly for those who share the author’s love and curiosity for flora. Roy’s reflections may at times seem bizzare (especially the chapters on the possible complications of taking trees as lovers or marrying them), but her quest – given the vast research and feeling put into this defence of those with barks, leaves and roots – is one hundred percent genuine. It is another shade of love and much like the romantic kind, it may seem weird, or difficult to understand, to those on the outside of it.