Peter Frankopan, author: ‘The world order led by the West is under pressure’

Author of The New Silk Roads on his abiding interest in the Silk Roads, China’s Belt and Road Initiative, and how India, China, Iran, the Middle East, and to an extent, Russia, are reaching back into the past to explain their present and future

Peter Frankopan is a Professor of Global History at Oxford University, where he is the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Director of the Oxford Centre for Byzantine Research. He has written two academic volumes – The Silk Roads: A New History of the World (2016) and The New Silk Roads: The Present and Future of the World (2018) – and a children’s book called The Silk Roads: A New History of the World – Illustrated Edition (2019) with Neil Packer.

A decade ago, in a profile for The Economist, Maggie Fergusson described you as “a Renaissance man”. Looking back, does this sound flattering or embarrassing?

I don’t think I ever saw that but, generally speaking, it sounds quite flattering. It’s a lovely thing for The Economist to say that about me. They are not naturally generous with praise. What they mean is that one tries and does lots of things and ends up doing some of them relatively well. That’s fine. I am very modest and also English. I am always awkward with compliments because I don’t know whether to say a “thank you” or just be quiet.

The most recent project you have worked on is a collaboration with singer-songwriter Katie Melua. Tell us more about this, and how it is connected to your Silk Roads research.

Oxford University invited Katie to come and teach students about song writing. She got in touch to ask if I’d like to collaborate on inspiring them with the Silk Roads, and encouraging them to write songs based on my book. She took 20 students, taught, encouraged and pushed them to develop around 15 tracks, which had a world premiere at the Sheldonian Theatre on 28th April 2022 at the ‘Silk Roads’ concert. It was completely magical. I had to pinch myself quite a few times. Most historians do not get their books made into albums.

You have written three books on the Silk Roads – two for adults, and one for children. When and how did you get so deeply immersed in this subject?

As a boy, I was interested in other people from anywhere in the world. But in my classroom, I was learning only about people from Europe. I had never really heard anything about the histories of India. I had never heard the name of Ashoka. I had never heard about the Gupta dynasty or Imperial China. I had never heard about other continents. Unfortunately, my school education was almost entirely about Europe, so even when I was a teenager, I was already interested in a much broader view of the world. I was hungry to know and learn.

I am relatively omnivorous. I like to learn about lots of things and lots of peoples. And the Silk Roads is quite a convenient umbrella term. Like all labels, it can be a bit clumsy but what really interests me is finding out how people have been curious about each other in the past and how they have exchanged ideas, goods, languages and genes. Clearly, in the ancient world of two or three thousand years ago, the exchange between South Asia, the Middle East, the Gulf, East Africa, Southeast Asia and all of Central Asia was extremely extensive.

We have very few people in Europe, only 700 million, a tenth of the world’s population. Yet all of our history books are just about ourselves. Studying the Silk Roads offered me a very nice way to look at a big region with lots of differences – geographies, cultures, ethnicities, languages, how people live, how they view gender. All these things got me interested. They allowed me to set up a different narrative as a historian with a focus on connections.

In The New Silk Roads, you wrote, “Once all roads led to Rome. Today they lead to Beijing.” Do you stand by it, or would you revisit that after the COVID-19 pandemic, and also Russia’s war with Ukraine?

Well, it’s a little bit provocative as a single line on its own. What I mean is that the decisions that are made today in Delhi, Beijing, Islamabad, Moscow, Riyadh and Tehran would seem to be more important than decisions that are being made in Paris or Brussels or Rome or London. And that would still seem to me to be correct. With the war in Ukraine, it’s very conspicuous that the government in India has taken a very different line to European and Western governments, as is the case in China and in Pakistan, and almost every single country in the world, in fact. The world order led by the West is certainly under pressure.

I don’t think that my comment is meant to say that China inherits the Earth but that this is an Asian century. India is not just an important but also an absolutely fundamental part of it. The transition is felt all over the world. It is recognizable. What India’s 21st century looks like has something to do with what’s happening in Ukraine but not that much. The imports of wheat are important for India, of course, but what’s happening is primarily a European problem.

The things that have been consuming us here in Europe – Ukraine now, and before that, Brexit – do not really matter to the one billion people who live in India and the 1.4 billion people who live in China. I think this is quite significant. It’s quite a humbling wake-up call.

Putting the present moment in a wider historical context, do you agree with the view that the crisis in Europe signals payback time for empire and colonization?

Yes, it is helpful to place things in context. It’s part of my training as a historian. But I think that the word ‘payback’ suggests that there is some kind of karmic cycle of history, that people get something back for what they deserve. That’s not my personal interpretation of how history functions. One can start by saying that this is suffering of millions of people – deaths of innocent civilians, old people, women, children in particular. Maternity hospitals are being shelled, and schools being blown up. The impacts of war are catastrophic; one would never want to wish for anybody to have this kind of suffering.

I think that probably the more useful way of looking at this is that we in the West have built a world of dependency where we have become dependent on Russian energy and, to some extent, food. In the same way, we have become dependent on China’s productive capabilities. Suddenly, when the tide goes out and things look slightly different, one is overexposed.

In the West, we have been good at taking the benefits of globalization without realizing what risks that exposes us to. It’s difficult to adapt quickly. That’s the main challenge. Adaptability is hard. India, for example, while taking the policy of neutrality or trying to sit across multiple different zones and regions, is seeing that it takes time to learn to do. It’s painful at times because you are put in difficult positions of balancing. In India’s case, there are complicated relationships with Pakistan, China as well as the United States, so one has to look north, south, east and west. In Europe, that’s not the way we’ve looked at the world.

We’ve tended to look only west, and probably there is a price that comes from that. We thought that people would just go on buying Mercedes Benz cars; the Russians would keep selling us energy. There would be no potential risk. It has come as a real shock to us in these last few months that global integration means that you can become more, but you’re more exposed than you thought or realized. We have to learn some important lessons from that.

Your analysis comes from a critical gaze but also a compassionate one…

I’ve learned that from studying Sanskrit texts. There’s no point being a scholar if you cannot try and see other people’s perspectives. You learn if you are ready to listen. We could be better at that in Europe than we have been in the past. It’s hard because we’ve all been told that the West runs the world and people will want to be like us. It comes as a shock to realize that other people can do things their own way and sometimes quite successfully.

You have been working on a book called Leviathan Russia and the Making of the Modern World. Would you mind telling us what it’s about, and when it will be out?

In fact, I was supposed to spend a year in Moscow in the archives. That should have happened two years ago. Because of the pandemic, I haven’t been able to. I need at least three or four years to complete that book. I’ve written a completely different one that will come out instead next year. It is about the history of human engagement with the environment and with climate. I was planning to work on it after the Russia book but Covid changed many things.

In March 2021, you had convened a conference on climate change in the Roman, Late Antiquity and Byzantine worlds. Did that feed into your new book?

Yes, the wonderful thing about being a scholar is that you always get to talk to people who are thinking about and working on interesting things. In the field of history, although quite often things are produced from archaeological digs, the fastest growing source of new information and evidence for historians today is climatic data, genetic material, and the way in which the sciences can help us understand the past. When you find skeletons, you can find out what those people who died maybe one or two or 3000 years ago were eating. There are other questions that you might get answers to. For instance: How far from home did they wander? What are their genetic links to other people buried nearby? How large were the communities that people lived in? You can develop mathematical models around migration and kinship from empirical data, which is a different way of doing history from reading what people wrote about in the past. This is a really exciting field of study, and it is developing quite quickly. So, yes, I organized a conference to bring together some of the latest thinking. I got people to come and share their research. As a scholar, when you hear what other people are working on, it sparks off your imagination in different directions.

Recently, you were part of a team that wrote a World Bank report called The Web of Transport Corridors in South Asia. How was the experience of working on a project where you had to collaborate with professionals from across disciplines?

It was enormously exciting. Trying to measure how to make differences, to devise policies and to see them implemented is a crucial part of using knowledge, information and critical thinking to improve the world around us. This project was important because we looked at how transportation affects social mobility, gender roles, education as well as more obvious topics like air pollution and intensifications of trade. It was a real pleasure doing it.

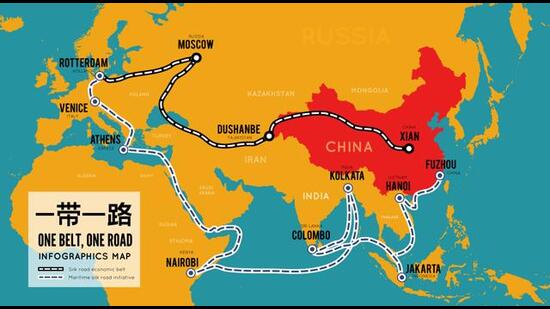

Speaking of transport, you edited a volume on China’s Belt and Road Initiative for the Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society in 2019. What parallels do you see between the Silk Roads of yore and the Belt and Road Initiative?

The Silk Roads are not real motorways taking you from Mumbai to Lahore to Kiev. The Silk Roads are abstract connections. They offer a kind of convenient label to talk about all kinds of exchange. But in the old days, like today, most people’s exchange is very local. Occasionally, there’s long distance travel that has a particular motivation, either for a holiday or if you want to discover something new or for work. In that sense, what China is doing is totally different because no one invested in infrastructure in faraway countries. The idea of trying to build up knowledge and language skills in other countries was never done and organized from a government point of view. It has always been a more organic process.

The difference between the Silk Roads of yore and China’s Belt and Road Initiative is like the difference between night and day. But what’s interesting to me is that all of these countries that I work on, including India, are reaching back into the past to explain their present and future. That’s the case for the Modi government in India today. The importance of India’s deep past is hugely important in the politics and the direction that the government sets for where India is moving to and going. It’s the same story in China, Iran, the Middle East and much of the Islamic world. It’s the same story to some extent in Russia. Putin is falling back on this idea of the origins of Russia a thousand years ago to explain its past and present. All such uses of the past are extremely interesting to me as a historian.

China’s use of the Silk Roads as a kind of label is just as a way of explaining that people across Asia have cooperated quite well for thousands of years, and maybe they can do the same again. This is true. States in Asia have had a long history of cooperation and stability, but not without problems. How India sees itself within this idea of Silk Roads is complicated. Silk production in India was extremely substantial. India was a fundamental part of exchange networks across the sea but also on inland routes. China has colonized the Silk Roads label to make it sound like it’s a Chinese project. In places like Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan and Iran, when they speak of the Silk Roads, they don’t think of China or India. For them, it is their own past. They think that their ancestors were the main organizers and beneficiaries of the silk roads. These connections and collaborations are important for us to explore today.

Could you tell us about your work with the Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation Programme, which was established by the Asian Development Bank?

This programme comprises 11 states – China, Mongolia, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, Georgia and Azerbaijan. Its aim is to improve economic co-operation. I was asked to help devise the post-pandemic economic recovery plan and chair a meeting of ministers from these countries to discuss and approve policy and implementation. Regional co-operation is now more important than ever.

You are also editing a multi-volume series on the history of Constantinople for Cambridge University Press. What aspects of the city are you hoping to cover?

I am the Series Editor, which means that my job is to find brilliant scholars around the world – people of all ages, nationalities and genders who are experts on the history of this majestic city. So far, we have released volumes on statues in the city and on the Hippodrome where horse racing took place. We are about to produce books on the water supply of the city, on its gardens, on graffiti in Ottoman Constantinople, on the role of the city in films – and then many more are to follow next year. We aim to produce around 80 books in total.

Before we conclude, tell us about your involvement with the Authors Cricket Club, and the matches that you have played in India. When are you visiting next?

I more or less hung up my boots when I was 25 but about 12 years ago, the club – which has a very illustrious history – reformed and I have been playing ever since. It’s a wonderful group of authors, including Sebastian Faulks, Jonathan Wilson, Tom Holland and many more who take sheer pleasure as middle-aged men to be playing cricket regularly. We came out to the Jaipur Literature Festival about 10 years ago, and played under lights at the Police Academy; and at the Bombay Gymkhana. Those games were not just highlights of the tour but lifetime highlights too. I am desperate to come back to India to play cricket.

Chintan Girish Modi is an independent writer, journalist and book reviewer

All Access.

One Subscription.

Get 360° coverage—from daily headlines

to 100 year archives.

HT App & Website