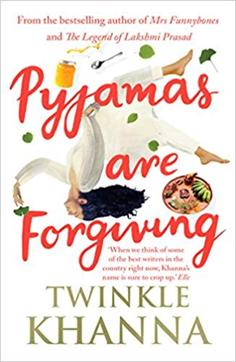

On a serious note: Twinkle Khanna on writing, her new book and being funny

Twinkle Khanna has been vocal about her feminism since she began writing. Now, with her new novel, Pyjamas Are Forgiving, she gives us #metoo book, with sexually liberated men and women and conflicting versions of what happened one night

It begins and ends with pyjamas. The first thing Anshu does after arriving at an ayurvedic spa, which provides the setting for Twinkle Khanna’s new novel, is take off her “too-snug” jeans and pull on a pair of pyjamas. “I tugged at the drawstring and made a double knot.” The comfort of loose white cotton is at least one thing she can rely on as her escape from midlife’s stresses -- work, family, past-- turns into a series of entanglements over the next 28 days. At the end of it, she will slip back into her jeans to return to her world, but this time reconciled with the limitations of her life, waist size and “too many Chinese meals.” “Pyjamas are forgiving in nature, it’s jeans that really know how to hold a grudge,” Anshu leaves a friend with these words of wisdom. “Pyjamas feature throughout the book figuratively. When we first see anshu, she is too accommodating, too forgiving, but towards the end she figures out how short your drawstring should be for you to be in control of your decisions,” explains Twinkle Khanna.

She isn’t wearing pyjamas, in case you are wondering. Khanna is dressed in a pair of jeans, delicately ripped at the knees, and a loose blue top. Her face is minimally made up and her hair swept back with a floral headband. Her vast living room is lit up by sun on one end and lined by the sea on the other. Sitting on a cozy blue sofa with her feet tucked under her legs and her hands locked around a cup of coffee, 43-year-old Khanna looks relieved. Not without reason. She has spent the last two years tied to her writing desk, turning an idea for a short story into a 220-page book spanning a month in the life of a woman who is put through an excruciating test: love or righteousness.

Along the way, she is faced with several situations typical to the life of a woman who is urban, single, independent, and not exactly young. Somewhere in her forties, Anshu is dealing with balance sheets, weight issues, an annoyingly settled sister, an increasingly concerned mother, and an ex-husband who has made his preference for younger, thinner women clear by marrying one. Similar to Mrs Funnybones in her cool imperfection and silly jokes, the protagonist of Pyjamas Are Forgiving makes one wonder if Twinkle Khanna is appealing to older urban women, a noatble audience for English-language writing. “Not deliberately,” says Khanna who points out that her readers include “a lot of men” and “school children”. She does hear back from a vast variety of women, “from diverse economic background, cultural background. Women who have a lot of restraints, women who want to live a different kind of life, young women aspiring to grow up.”

Twinkle Khanna has been vocal about her feminism since she began writing. Mrs Funnybones is often struggling to balance home, career and kids; she fails most of the time. “Indian woman’s work is never done because she has to do all the stuff that was dumped on men earlier, like dealing with doctors, talking to bankers, bribing random government officials, threatening accountants, and still has to change diapers, tolerate crazy mothers-in-law and jump at her family’s commands,” Khanna writes in a column. However hard it is for her readers to imagine her as an average working woman -- she was born to film stars, became a film star, married a film star and then became a well-paid writer and interior decorator -- she at least tries to break out of her bubble. Her last book, The Legend of Lakshmi Prasad, featured four stories of ordinary men and women underlined with feminist themes, from female friendship to menstrual health.

For the last story in the book, The Sanitary Man of Sacred Land, she researched the work of Arunachalam Muruganantham, the well-known inventor of a low-cost machine for sanitary pads. Earlier this year, Khanna produced a film, Pad Man, based on the same story that starred her husband, Akshay Kumar, as the rural entrepreneur.

Now she has given us a #metoo book. The world of Pyjamas Are Forgiving, an isolated place where an estranged couple and a whole bunch of strangers are thrown together for a month, is set up perfectly for a #metoo twist, with sexually liberated men and women and conflicting versions of what happened one night. Earlier this year, asked at an interview about her views of #meoo, she had echoed its motto: time’s up. “All of us have been in these situations and some of us have scrambled out of them, sometimes thanks to sheer luck,” Khanna says. Why set the story in an obscure ayurvedic retreat and not Bollywood whose #metoo stories are dying to be told, even if veiled in fiction. “It’s difficult to write about things that are so close. I write to escape and not to sell thousands of copies,” she says. “It’s also a world that I am bored of.”

She was never really interested in that world to begin with. “Acting is an art. I did not have that gift,” she says. In a seven-year movie career, Khanna acted in 16 films: action, romance, comedy... She says she didn’t enjoy a single moment in front of the camera. She can be brutal about her time in Bollywood. “Like doctors’ children are encouraged to become doctors, my parents insisted I had a bright future doing pelvic thrusts with a pink bow on my head,” she writes in a column. She spent most of her waiting time on film sets reading -- or knitting. “My spot-boy would tell me, ‘please don’t do this or people will call you auntie,’” she recalled in an interview. She was 20 when she shot her first film. “My defences were very high. You don’t want people to see the real you,” she says.

Twinkle Khanna had wanted to write since she was 16; she began when she was 38. “Writing lets you hide. Your defences are still high, but writing allows you to climb over that wall and look at the world.” She still crouches into herself before she has to face a camera, she says. “I dread it. I have to tell myself, ‘I am lucky to have this opportunity’.” She recently froze before heading out to pose for a fashion magazine. “I was so stressed that I had to do a few minutes of yoga. I chewed off my nails. Who does that just before a fashion shoot!” Now that she is free to write as much as she wants to, that’s all she does for long stretches of time. “I am very driven. When I am immersed in the process, I don’t do anything else. If I receive editorial comments, I attend to them right away,” she says. “While I was working on this book, I wasn’t present for my family at all.”

Her writing is famous for being funny, but Khanna actually takes her writing life very seriously. She observes minutely everything around her including potholes. Even the jokes are collected and revised for days before they are consigned to print. “All those lines don’t come to me at once.” The latest book is shaped from “copious notes” she took while being enclosed in an ayurvedic retreat a few years ago. The title too emerged from her notebook. “It was right after one Diwali. After days of eating and drinking, I was standing in front of my half-open closet and reaching out for pyjamas when the thought came to me. I noted it down.”

She also takes her reading life seriously. Asked if she reads any Indian writers, she named Jhumpa Lahiri, Rohinton Mistry and William Dalrymple. Her current reading list contains several titles nominated for the Booker Prize: Hot Milk, Eileen, My Year of Rest and Relaxation.

The same earnestness marks Pyjamas Are Forgiving. Most of its characters are sketched out elaborately and most things happen for a reason. It’s not always a smooth read, however. It’s distracting to find Anshu crack jokes that sound just like Mrs Funnybones’( It [sex] is not always that vigorous, you know, sometimes you just lie down flat on your back and think of George Clooney!); tiring to read scene upon scene of the residents doing yoga, ingesting ghee shots, and walking round and round a garden; and disappointing to notice that ‘the other woman’ of this otherwise feminist novel is a stereotype: she is shallow, territorial and has fake breasts. Khanna says she “couldn’t afford to layer her beyond a point” because she is mainly shown through the eyes of the man. “ [Through her] I was trying to show that he is so callous about people. It was a way of revealing his character.”

Writing for her is not always easy, says Khanna. “It can be hard. You have to imagine, observe, create, recreate -- repeatedly.” At times, she says, she fears she won’t be able to do it in the absence of the perfect setting. “I feared I won’t be able to do with without coffee. But I was able to. Or without my lucky laptop. I still managed.”

Does Twinkle Khanna ever fear the jokes won’t come to her? “Often. When I have to go on stage after someone has introduced me and said ‘she is going to make you laugh’, I wish could have an epileptic fit and collapse.” But she always manages. “I take a deep breath. A reminder that if I can be myself that will be good enough.”