Lockdown Diaries: Mirrored in the Ganga by Jerome Armstrong

One of the few foreigners to stay back in Rishikesh during the lockdown, the author notices that the Ganga is cleaner and purer than it has been in a long time.

The impeded stream is the one that sings. - Wendell Berry, Our Real Work. In Standing by Words. Counterpoint, 1983.

“It was not until I landed in Rishikesh with no means to leave, for weeks on end, and living on the Ganga amidst quietude, that I began to gain an insight into the way nature teaches those who listen.”

* * *

Rishikesh has always been full of tourists, but things are shut down now, and I am one of the few remaining. First the state borders, and then district borders have closed, and movement has become tightly controlled. At first, there were about 2,000 foreigners stranded in Rishikesh; now it seems less than 200. I didn’t plan to be here, but given the lack of alternatives, it’s where I chose to be.

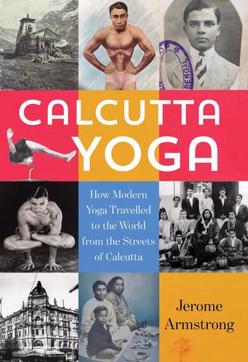

I was travelling through India in February and March, on a book release tour for Calcutta Yoga. In the middle of March, everything was postponed, but my flight back to America was not until March 26th. I decided to go to Rishikesh on the 20th and stay there for six days. Then, on the 23rd, India closed all its borders, and the flight reservations I had were cancelled and refunded. I would stay in India longer.

Not just stay, but stuck, without an option to leave, given family complications back in the States, at least until the end of April. But it seemed perfect for me, because for the past two years, I’d compiled research for a travelogue along the Ganges. It was as if Ma Ganga were telling me, “If you want to write a book on travelling up the Ganges river into the Himalayas, you will need to stay longer, in Rishikesh, to get to know me better...”

Rishikesh along the Ganges, back in the 1920s, and even up until the 1950s, was just a small village. Yet, from the accounts written, it was a wonderful place filled with magical encounters and spiritual seekers where, just as the name suggests, the rishis gathered. Seekers practised yoga and meditation outside, having nature and the animals as teachers. From the 1960s onwards, a larger footprint of humanity arrived in Rishikesh.

In the late 1960s, the Beatles famously resided on the outskirts of the town, and thereafter, hippies started travelling to Rishikesh from all over the world. And since then, the growth trend has not stopped. Rishikesh has become the mecca for international yoga. A place where thousands arrive as yoga tourists, and hundreds stay a couple of weeks or months to be instructed in and practise yoga and meditation, spending lots of money. Alongside the river, concrete ashrams and businesses sprang up, and residential guest houses climbed up both sides of the hillside along the river.

As a result, Rishikesh has completely changed, and seems like just another noisy India place that blows its horn all day long. But that is on the surface. The Ganga power is still here flowing through it all. No matter how crazy everything else is, the river is the same, just flowing by, silent in places, current swirling in others, and places where the rapids churn and splash.

There can be complete chaos all around, or complete silence all around, as far as human activity goes, and the river will remain the same; the same regardless of anything. You could say the river is a form of being a silent witness to everything, accepting all with an embrace.

I recognized this intellectually but not with experiential knowledge. Amidst the noise of humanity and machines today, it is difficult to sustain or recognize such a deep recognition, even in Rishikesh.

I had many magical encounters along the way of a 2000 km journey along the Ganges river, but sometimes, it seemed as if I were running up the river toward the Himalayas, in order to get away from the noise of India as soon as possible. Even in those moments though, all I had to do was stop, look around, and there was something going on in the moment which pulled me into the present. Despite whatever noise, pollution and uncleanliness was all around, the people, animals and the place kept me engaged. But I couldn’t help but be nostalgic. The India I romanticized about was in the past, before the waves of its modern industrialization, before all of this modern noise.

That pristine Indian experience is a perspective which was often shared about the Ganges, almost mythically, and it contrasts sharply with a modern survey along the Ganges, which includes ecological disasters, extreme poverty, and the cultural loss of the old ways.

I wanted to include both of those perspectives in writing about my journey along Ma Ganga, but I had no real experience of the former. Whenever I spoke with old hippies or babas, who were around back in the 1960s and 1970s, and even myself, sort of, when I first travelled to India in the 1990s, there was a longing for the India of old. That’s why, when I landed in Rishikesh, and India locked down, I realized it was a miracle. The city turned off its horns and the noise stopped. I was halted, right on the Ganga, as if a part of time had moved back a century.

I am staying in a hotel room on the west side of the Laxman Jhula foot bridge, nearby the Laxman Murti Chowk. After a couple of months travelling all over India, and having a book to complete, I’ve been provided with a place to stay and write a while.

Everything was closed at first, then enough shops opened for a sense of regularity, and a routine emerged. It is nothing near the freedom of movement I’d known in Rishikesh in all my previous travels to the place, but I made the time work as well as possible, getting exercise daily and finding food. And the weather is exceptional, the type of which you forget about, because it is just right.

Apart from the stores and shops open until 1 pm, the only nearby choice to eat out is at a restaurant just around the bend in the road from my hotel, and it is open from 9 am till 9 pm. Well, half open. You’d have to bend over and crawl in the half shut door, and then hide out on the second floor while eating. Not unlike a conflict zone, the patrons want to be able to shut the doors immediately.

I’m in my room mostly though, and able to write and practise as much as I desire. I’ve a desk near the window overlooking the Ganges, along with a bed and a bathroom. The roof of the Ganga temple is below, where monkeys and cows come by for scraps of food tossed out the windows. Next door to my hotel, the Lotus Cafe is closed, but their wifi is still on, and just before the lockdown, I synced both my mobile and laptop, so both now work inside my room. I bought a cotton yoga mat to practise asanas inside. Twice a day, I go upstairs to the hotel terrace to exercise during the day, and then I meditate at night.

As the days have passed by, I’ve sunk into the place more deeply. There is nothing to jar one out of going deeper and deeper. I hear car and motorcycle horns in the distance during the morning break, but otherwise nothing for hours at a time, and all throughout the night. There is no noise except for voices, occasional music, chants, drums, bells, the animals and the river. Outside, smiles of acknowledgement and babas saying “Hari Om” as we passed by each other are nothing new to Rishikesh, but it has become ordinary for me now, with regular faces and encounters.

Friends learned of my predicament and have sent me messages of encouragement. One from Italy told me, “Everybody is leaving, Rishikesh now has only a few people, and you are one of those few. So yes, enjoy the baths in the Ganges, the nourishment by the air, and then use all of that energy toward this book. Write the best book you’ve ever written.”

Another from Calcutta wrote: “You are locked down in Rishikesh, the place where all the rishis and munis sat and meditated; these are holy grounds. Right now you are going through a transformation. You are getting more attuned to nature. Your lifestyle is becoming like the ascetic Hindu meditations. You are blessed.”

The Ganga is my main teacher here. I look into the river from my room. I take a walk along the river. I take a morning swim in the river. I gaze at the river from the terrace. I watch the sunrise over the mountains on the other side of the river and then watch the sunset over the bend of the river on the other side. Every day, and every waking hour, the Ganga is near. And when I pause and look deeply, it is like a mirror that I look into which reflects back, magnified, whatever emotion I carry. If I am peaceful, it would extend the peace. If I were sad, tears would flow. If I am happy, I’d smile more and feel well. If I felt love, the heart would be filled. I guess the best way to describe it is like a mother and her son. The mother can always see right through, and the son cannot keep anything hidden for long.

I met a swamiji here who lives outside. Often I go to him to ask about my struggles of the future and past, and he answers my questions. “Turn everything to being happy,” he replies, encouraging me to accept the present moment. “The world is on pause, and your work is here. Let everything go.” We often laugh too. When I told him that I felt like I was the only one left at times, he replied, “You are everyone.”

Another day I replied of my thoughts being “so confused” he responded, “Don’t think” and spoke of bhakti as a means for my mental engagement with the world. “The events will come, and then you can deal with them. Now, these days,” he goes on, confirming a sense of urgency to be in the present, which is easily done here alongside the river, and by observing the animals.

One day, I watched a monkey playing with a large white bag which could easily fit over its head. He put it on, so he couldn’t see, then moved quickly twenty feet away, and took off the bag covering his head. He looked around confused, as he’d just done an experiment on his own mind. He must have liked it, as he turned around and did it the other way, with the same reaction. Was he laughing? Did he get high? Was he trying to get enlightened?

Outside my window, I watched as two monkeys made love. Just below me, they were atop the Ganga temple, in a place where the cement dips below the bricks, so they were alone. Afterwards, I tossed a mango out the window. She went to eat it, but left scraps for him. Then a cow came along and finished off the peelings. Further below, I watch the Ganga flow all day long.

There is a French baba living nearby under the old bridge along the Ganga. He’s been there every day for the past week. I visit him and meditate there, listening to the sounds of nature. Within a few days of the lockdown, the water of Rishikesh became pure. The Ganges river is at its cleanest and at its purest in a long time. Downriver, I imagine all of the villages and cities along the Ganges are witnessing this, and the dolphins and wildlife are experiencing a healthy river. One night, I asked how long it would take for the entire river to be clean again. The baba replied, “Within 30 days all of Ganga will be healed.”

There’s a dog who stays there too. He likes to hear his bark echo off of a rock wall, across to the forest mountain side, and then up the river. Is he barking to hear himself? After he hears the echoes fade away, he does it again. I count three, but who can say how far away the dog can hear his own voice echo as it ricochets up the river?

Another evening sitting in meditation, I felt the exact moment when the day turned to night, through the breeze. It blew down the river, like a wave that rolled over, changing the temperature by a few degrees in a short instance.

Once, I thought I heard something mechanical. It was a bit irritating, as everything else was silent. Then, the baba came out of his meditation.

“Listen to the symphony.”

He was remarking on the sound, which I thought was something like a generator. Instead, I listened with more intent, and realized the sound contained a multitude of frogs, up and down the river, making the same sound. None of them were near, and so their sound all melded into one from afar. It went on for about half an hour with many intimate moments of breathing and awareness. Then, they all stopped, at the same time. I couldn’t help but laugh, as did the baba.

“It’s not as if any of this is new,” said the baba. “It happens every day. It’s just that in our noisy busy world we are unaware; we miss it.”

Jerome Armstrong travelled across India from 2015 to 2019, staying for weeks or months at a time while researching for and writing Calcutta Yoga. His PhD in Conflict Analysis and Resolution is from George Mason University. In the early 2000s, he was one of the first popular political bloggers. He co-authored Crashing the Gate: Grassroots, Netroots and the Rise of People-Powered Politics (2006) and worked in digital media for political campaigns in the United States and internationally for over a decade, during which time he co-founded Vox Media.