Ira Mathur: “The dead do not leave us”

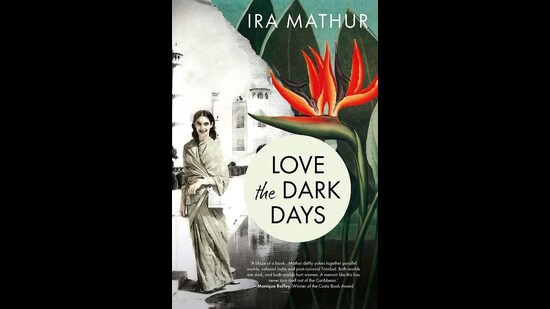

At the Jaipur Literature Festival, the author of ‘Love the Dark Days’, a memoir, recollects royal betrayals and a life far from her roots

Often, memoirists don’t declare that their recollection is a version of the truth. In that regard, is a memoir a counter fiction that pushes back against the fiction that a family tells about itself?

I had to [put that disclaimer]. If you put five people in a room and something happens — a betrayal, an accusation, a scene — you will get five versions. Memory twists, shaped by grievance and need. A word becomes a wound, a touch a blow. One will remember an insult never spoken; another a debt never owed. Families stuff their skeletons into closets, keep up appearances, oppress the weak who suffocate in that dark. This book resists that lie.

I’m a journalist. The truth is in my blood. Love the Dark Days was first published by Peepal Tree Press in the UK in 2022. Speaking Tiger later acquired the South Asian rights. In London, journalists known for their tough questions — Michael Portillo on Times Radio — spoke of its raw honesty. The Guardian named it one of the best memoirs and biographies of 2022. In Trinidad, it won the [OCM] Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature [in the nonfiction category]. Not for its Nawabi setting. Nor for the Nobel laureate from St Lucia [Derek Walcott] who read my work. But because it was unsparing. I laid myself bare — my vanities, my blind spots, the ways I hurt those I loved, even a breakdown. Critics have called it brave, but it was the only way I knew how to write.

The description of Burrimummy (grandmother) being buried and Angel (Ira’s sister) suddenly discovering the former’s mortality can be read in conjunction with your lifelong endeavour to gain your grandmother’s love, which you didn’t get. Consequently, you were jealous of your sister. Would you like to talk about the relationship dynamics and how you want to remember the dead?

When Angel wept for my grandmother, it was the grief of a sudden loss too vast to grasp. I understood it, but I did not feel it the same way. I had grown up expecting absence. My father Col Mahendra Nath Mathur was an officer in the Madras Sappers, and we moved every three years — Chandigarh, Simla, Delhi, Bangalore: a new school, a new language, a strange house, a different landscape. Hence, no friends. I learnt detachment. It was survival. It is only now that I see that not getting that affection was a gift. By not being favoured, [a] free spirit. I stopped being jealous of my sister when she came to Tobago where the family dynamic changed. It’s a small cast of characters. I adore them all. Who says that love requires virtue or should be deserving? Perhaps none of us deserved it but we loved one another.

The dead do not leave us. Literature lets us hold on to them and summon them back into the world. I see Burrimummy (wild and brave who left a man from a powerful family because she loved him too much to tolerate infidelity); I see her hands on every piano. She played thunderously, beautifully. I see my brother Varun — tall, gorgeous, charismatic, a man who left every woman he met weak-kneed; that big laugh, that striding walk. They both tore through their days with blazing recklessness that made me see life was big. Some neglect or hurt was a small price to pay.

I still think of my elderly parents as forever young, beautiful, and desired, waltzing on a wooden floor in the officers’ mess in Bangalore to a live army band. They showed me beauty.

You supply strands of India’s political history and fuse it with a personal narrative, given the significant positions people in your family occupied during the British Raj and later. Or as your Burrimummy writes in a letter: “Darling, our lives are intertwined with the British dominion over India between 1858 and 1947.” You wrote of how the memory of your grandfather, Lieutenant-Colonel Fakhr ul-Mulk, Nawabzada Muhammad Saied uz-Zafar Khan Bahadur, as the nephew of the Nawab of Bhopal was erased from the current family in Shamla Kothi. These nuggets are interesting but can derail the personal narrative. What caution did you exercise in interweaving these strands?

The personal is always political. I don’t care about how the book makes my family look. I care about the truth. It reflects my Hindu-Muslim family, my India — where I belong.

My grandmother’s family colluded with the British, and that pecking order remained — power, skin, wealth, chaos. My ancestor General Nawab Sir Afsar-ul-Mulk Bahadur’s (1852–1930) father was brought from Uzbekistan to help crush the 1857 mutiny. He suffered when he shot Muslims, just as Hindus and Muslims suffered when they shot their own. My Hindu father, an Indian Army engineer, fought against Pakistan in 1965 and 1971. He removed mothers’ duas from the pockets of young Pakistani jawans dead in landmines he had laid. They looked like him. Years later, he married my mother, a Muslim in a country where a million Hindus and Muslims butchered each other during the Partition.

This is a personal story, but also the story of the Bhopal royal family — of my grandmother, Shahnur Jehan Begum, leaving that world, of my grandfather, Nawab Saied uz-Zafar Khan, erased from Shamla Kothi, the home built for them by the last Begum of Bhopal.

My brother was part of India, a son of a Hindu father who fought Pakistan and a Muslim grandmother who composed music for Pakistani jawans. When he died at Johns Hopkins, still warm on the hospital bed, I took my laptop to the basement and filed my column for the Trinidad Guardian. That column is in the book. History was there, too. Varun died of the same (colon) cancer as his great-grandfather, General Obaidullah Khan, [eldest] son of Nawab Sultan Jehan Begum, Ruler of Bhopal [from 1844–1901].

For me, it’s either the truth or nothing. That said, I have used the truth as a shield against erasure and injustice and held back when the truth was a sword to hurt the living.

You use the gerund ‘floating’ to signal how you were getting pulled by Burrimummy. Then, your mother saw a dream in which you were “wearing a white dress, floating towards her”. I did feel that you were ‘drifting’, too — with Burrimummy at the centre of the sphere you wanted to enter. You drift away from her and float around the circumference to attract her attention. What do you think about this?

That’s a clever observation. Burrimummy always told my favoured younger sister, Angel, she arrived on a magic carpet, carried by angels.

I was a child floating or drifting towards — acceptance, love, and safety; a place where skin colour, my half-Hindu, half-Muslim self would not set me apart.

At 22, at my mother’s cousin’s wedding in the Rampur royal family, a woman looked at me and said I might suit her son. My great-aunt cut her off — “Oh no, she’s a Hinduani”.

That was when my idea of family changed. I thought it was something you were born into, something that held you. But home was not nationality, race, or caste. It’s found in kindred spirits, in human hearts. The New World was cut off from old-world prejudice and atavistic hatred. My life in Trinidad and time with Derek Walcott in St Lucia — a poet laureate who recreated the New World ‘leaf by leaf’ in his epic Omeros (1990), his answer to Shakespeare — reminded me of this. I drifted far from Burrimummy but she remains my centre. Perhaps I’m suspended in this space of yearning but it helps me to write.

When you became a mother, what did you do so that your children didn’t feel the estrangement you felt growing up?

I was a young mother, working 16-hour days in radio, television, and print. Inherited trauma is a terrible thing, and I made the same mistakes — not in the way Burrimummy did, but by being absent and too busy. Privilege doesn’t erase trauma. You are always deciding: fight or flight.

It was my grown daughter who broke the cycle. I said things without thinking, cruel things. “I’m dead to you.” Things like that. My great-grandmother spoke like that. My grandmother. My mother. One day, my daughter said, “Mum, I’ll never speak to you again if you speak to me like that. There are boundaries.” She cut me off for a year. My son pushed back when I pushed him to do this and that. “I am a sovereign being,” he said, “not your extension.” He stood apart. I admire this younger generation for standing up for themselves.

I wanted my children to know I loved them unconditionally, but their lives belonged to them.

In South Asian families, fear drives love — fear that children won’t be educated, settled, or successful enough. Trauma is normalised with “I want what’s best for you”. Cruel things are said “for their own good”. Parents believe comparisons push children forward, and that harsh criticism will vault them to success. But harsh words, even with “love” towards our children, leave wounds that last a lifetime.

Would you say that writing violence is gendered, too, and given how you write trauma and violence, they may not effectively be rendered by a man?

A rape every 15 minutes, a dowry death every hour, and a case of cruelty by a husband or his relatives is reported every four minutes. These are not just numbers; they are lives.

But violence doesn’t happen against women alone. In rural Haryana, 52.4% of men report [gender-based] violence, mostly emotional and some physical. Men, conditioned never to admit weakness, suffer in silence. Same-sex couples face brutalities — honour killings, forced marriages, and violence from family, police, and the state.

We have normalised violence in ways that make it almost invisible. A slap followed by a meal, a beating followed by a gift, an insult disguised as a concern — “I want what’s best for you.” Women absorb it. Men do, too. They are given control, but the burden to provide, protect, and dominate comes with it. And yet, for all their power, they are trapped as well.

This is why men and women can both write about violence. Because we have all lived it. We have all been shaped by it. Because, in the end, no one escapes it.

How is life in Trinidad? Given that you’ve lived everywhere, which place do you call yours?

I love Trinidad — it’s a magic isle. I love India. But nothing is mine. It belongs to itself.

Your writing reflects this duality. At one point, you say, “You’re here and not here.”

I was born in an army hospital in Guwahati, Assam. I have lived across India but cannot say where I am from. In Trinidad, we are all hyphenated, all claiming everything. It is a world inventing itself. A place where the old hatreds and languages are forgotten, where everyone starts fresh. A tiny new world of VS Naipaul, Derek Walcott, and Brian Lara was created by people from four continents — [with a history of] indentured labour, slavery, and colonisation — percolating, creating a new identity, making herculean waves. Here, people go freely to one another’s mosques, temples and churches to worship, mourn and celebrate. Here, during our festival of Carnival, a beggar and judge share drinks. All societal barriers are broken.

India is my past, the history I carry and always in my blood and my children’s. Trinidad is my present, where something new begins. One is memory, the other is a possibility. Sometimes the two countries switch places in my heart. I’ve loved the dark days in both.

Saurabh Sharma is a Delhi-based writer and freelance journalist. They can be found on Instagram/X: @writerly_life.