Saikat Majumdar, author, The Middle Finger – ‘Novels never feel completed’

The author talks about his new novel where the protagonist is caught between twin identities – brown in the US, savarna in India – that complicate her academic life and her loves and friendships

Professor of English and Creative Writing at Ashoka University, Saikat Majumdar’s new novel, The Middle Finger, revolves around poet-professor Megha Mansukhani, who is consumed by self-doubt, adored by students, and caught between twin identities – brown in the US, savarna in India – that complicate not only her academic life but also her loves and friendships

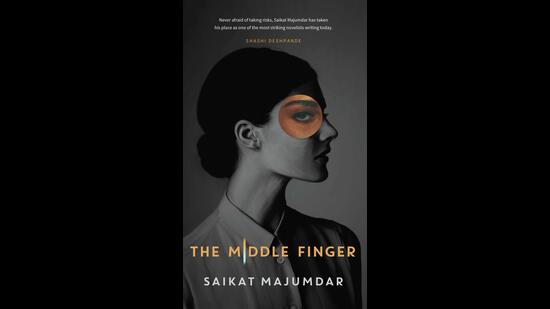

What’s the story behind the gorgeous book cover? Even the cover of your last novel The Scent of God was stunning. How involved are you in the process of cover design?

I’ve been very lucky to work with an exceptionally talented cover designer, Pinaki De, since my first novel. He has done covers of three of my novels and two non fiction books. Pinaki’s great strength is that he is a literature professor as well as an artist, and he reads the manuscripts of the books several times before starting on the design. He has a way of touching the very pulse of the book with the cover; more than the story, he captures the defining emotions. This particular cover is unique as the publisher also came up with a special jacket design – there are two covers, the second one peering through the hole in the first.

Who or what were you thinking of showing the middle finger to while writing this novel? To what extent do you care about how people respond to your writing? Are you, in any way, like Megha – the protagonist of your novel – who squirms when her poems are performed?

Ha ha, great question! The title comes from a medieval Jain retelling of the Ekalavya story recounted by Wendy Doniger in The Hindus: An Alternative History. In this version, it is Arjun who cheats Ekalavya of his thumb. Drona becomes angry with Arjun upon discovering this, and offers the blessing that a Bhil warrior will be able to shoot arrows without his thumb, using his index and middle finger. The phrase suggests unusual or unexpected strength that is rudely disruptive of established power, and it has a literary implication in the novel. Every writer, I think, has a bodily reaction when they hear their words read aloud by someone else! But it’s a situation faced more by poets than by novelists.

Megha seems to represent a certain type of American desi academic – the Fabindia loving capitalism basher networking furiously at the Modern Language Association Convention in Chicago, and holidaying at Neemrana Fort Palace. You seem to have had a lot of fun writing this book…

Well, yes... but Megha is also a bit lost in this world, no? She’s been to very good schools, but she also inhabits a world where literature, particularly poetry, occupies a precarious place, notwithstanding its underground appeal. And privileges of race and labour alter depending on where you are and how your skin colour merges – or does not merge – with the background. Also, a culturally privileged and imaginative articulate person can be quite out of sync – even cornered – in a world dominated by networks of material power and wealth. I think Megha realizes the irregular relationship between the imagination and material power quite early in the novel. It’s confusing – and always unpredictable.

The precarious nature of the academic job market is a key theme in the novel. Surprisingly, Megha, who seems most anxious about it has alumni networks to draw on – Lady Shri Ram College in India, University of Sussex in the UK, and Princeton University in the US. Is she genuinely worried, or is self deprecation considered sexy in her circles?

The worry is genuine, given the realities outlined above. For anyone out in the academic job market in the West, it’s a terrible world – has been since 2008. Prestigious education brands weaken considerably when it comes to poetry or the arts – or at least their socio-aesthetic attraction does not translate into stable careers. Megha is worried but she isn’t really an anxious person as such – she’s quite whimsical and impulsive.

What kind of effort did you have to put in while writing Megha in the US, and Megha in India? They seem like two different creatures in terms of their position in the social hierarchy, where they live, the money they make, and how they express desire.

A brown person’s life is radically different in the US and in India – the experiences, the privileges, and the identity itself feels changed. Her racial marginalization shapes a kind of poetry for Megha in the US, and once she is in India, in a relative bubble of privilege, her artistic voice is stunted for a while. That is also why Poonam is such a crucial presence for Megha, for political reasons that are also deeply personal.

Mentoring is another significant theme in your novel. There is a hint of a possible romance between Jishnu and Megha. The expectation is set up, then shattered. Did you hold back because you were concerned about how readers might receive this student-teacher relationship in a post-MeToo environment?

I wanted to write a story where Drona eventually turns away from Arjun to support Ekalavya. Jishnu is another name for Arjun, so that’s a hint. Also, I guess I ended up showing Megha slowly but unconsciously moving away from certain privileged male models of brilliance. She has much more in common with them than with Poonam, and yet Poonam’s friendship reveals many things to her, including realities of her own life.

In the book Teaching Community: A Pedagogy of Hope, bell hooks writes, “Eroticism, even that which leads to romantic involvement between professors and students, is not inherently destructive. Yet most individuals who oppose consensual romantic bondings between professors and students act as though any surfacing of sexual desire within an institutional hierarchy is necessarily victimization.” What are your thoughts on this subject?

I think the erotic defined in a very broad way – of an exciting chemical reaction of one human live wire touching another – is fundamentally true of successful education, and definitely so in the artistic fields. Art itself forges a kind of erotic connection. But to turn such a connection to a sexual or romantic relation is dangerous, particularly when the two individuals are in a mutual power relation, as teachers and students are. It’s a very complex subject and everyone from Plato to bell hooks and Jane Gallop has talked about it, and intimacies of the teacher-student relationship figure variously in the Indian Gurukul tradition, both in myth and reality. But not everything that sounds attractive in art, myth, or imagination, is desirable in reality.

In The Scent of God, Anirvan is attracted to two of his teachers – Sushant and Kamal. Sushant’s pointed cheekbones, beard, and tight shirts are a source of fascination. Kamal’s saffron robes with the whiff of cardamom, agile cricketer body, and lean arms mesmerize Anirvan. What draws you to this subject of desire that is felt but can never been fulfilled?

There are desires that are never meant to be fulfilled. Their very nature is transgressive and their very existence can be a threat. The desire the student feels for the teacher – as for instance in The Scent of God – is not even necessarily of a sexual nature as such. It is a kind of immersive admiration, a desire to imitate and become, a hero worship, at most an adolescent crush. The fulfilment of such desires is successful mentorship.

What challenges did you face while writing about the intimacy between Megha and Poonam? Your epigraphs from Plato’s The Symposium and Hemavijayagani’s Katharatnakara say more about it than your words in the novel. The sexual tension between these women is intense. What stopped you from giving them a grand lovemaking scene?

The relation between Megha and Poonam is the heart of the novel. And yet it is a relation very difficult to express, for the writer as well as for the characters. The social and cultural differences between them make up oceans. They don’t even quite know what they have come to mean to each other as their lives get entangled in unexpected ways. I think a lovemaking scene between them would have been out of place. Things are never that overt in the novel. But there are possibilities, which are not fully realised within the scope of the story.

In her book Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom, bell hooks writes, “Professors rarely speak of the place of eros or the erotic in our classrooms. Trained in the philosophical context of Western metaphysical dualism, many of us have accepted the notion that there is a split between the body and the mind. Believing this, individuals enter the classroom to teach as though only the mind is present, and not the body.” Do you agree?

Absolutely. To be modern in a Western sense is to privilege the mind over the body, theory over data, the abstract over the concrete. Intellectual traditions have internalized this, and modern education is a process of increasing abstraction, theorization, and now virtualisation/digitisation. The arts, however, involve an unexpected return of the material body and its disruption of the realm of the mind. Older forms of in-person knowledge, such as memory, rhythm, enactment, incantation, liturgy have been pushed out of place by modern education. Poetry, when carried on the body, involves a return of the physical in the classroom. Artistic education, in this sense, is an intense physical education.

That makes me think of Rory from your novel, who choreographs Megha’s poems and dances to them on stage. And it makes me think of Poonam, whose heartfelt speech in church moves Jishnu in a way that makes him feel completely useless because he is so cerebral. In what way is their relationship to the mind-body complex mediated by religion and education?

That’s a really interesting question! Both of these are examples of the embodiment of art, of giving physical form to imagination. Rory’s dance is mediated by temple traditions, even though he’s not religious himself. Poonam’s poetic speech is certainly inspired by her faith, particularly her need to express herself through the church sermon. Some form of bodily presence and participation has always been central to many religions. Dance, prayer, sermon, they all invoke physicality, and particularly real-time communities of people. Modern secular education privileges the mind over the body and celebrates theory and abstract thought. Religious texts are in perpetual pursuit of meaning from the eternal Absent, God, but that’s a different abstraction. The practice of religion usually involves certain communal arrangement of the body, and that arrangement has always inspired art.

The publisher has not marketed The Middle Finger as a queer love story though the relationship between Megha and Poonam is at the heart of the novel. Do you think that calling it a queer love story might build up certain expectations that seem unfair?

Queerness is very much a process of exploration in this novel, even more so than in The Scent of God where in the end at least the characters know their sexual identities firmly. Megha, who is an adult, and far more aware of different sexual identities, with many queer friends of her own, is still working through her own. I do show her as turning away from certain aggressive models of male brilliance early on, but that doesn’t necessarily indicate her sexuality, or at least, not yet. I think physical desire is subordinated in this novel to the need for relationships, for the space of a home, all of which the protagonist lacks. All of that being said, the unexpected magic of Megha and Poonam’s relationship is at the heart of the novel. But it is a relationship that develops when no one is looking – certainly Megha isn’t – through the banalities of everyday life, setting up a home, going grocery and furniture shopping – the unnoticed trivialities of domestic labour. Their social difference makes a consciousness of this relationship difficult, though they reckon with this relation as the novel comes to an end.

This book seems to have the makings of a sequel. Are you working on one? What happens to Vivek after his spat with Megha? Does Jishnu become a politician like his father? Does Megha move back to the US? There are so many questions that you leave your readers with.

That makes me very happy, as it means the characters have come to life enough for the sensitive reader to want them to live on. Perhaps that’s the mark of a fictional character’s success – they spill beyond the frame the story gives them. The experience of writing novels have taught me that novels never feel completed – the endings always hold more beginnings – perhaps because there is no real closure in life for anything. The added challenge of writing a story with unusual relationships is that not everything can be realized within the frame of the novel – you can only show some possibilities as sprouting. The growth of the tree may be a different project, a different narrative. I’m happy that the ending of the novel feels like the beginning of new possibilities, and new stories. Am I done with these characters? Do their stories need continue telling? I think time will tell.

Chintan Girish Modi is a freelance writer, journalist and book reviewer.

All Access.

One Subscription.

Get 360° coverage—from daily headlines

to 100 year archives.

HT App & Website